The “through-the-scope” (TTS) balloon dilation technique has several advantages. It can be performed as part of the initial endoscopy, and does not normally require fluoroscopic monitoring. The results should be obvious immediately, and the endoscope can be passed through the stricture to complete the endoscopic examination.

Bougie dilation

Dilation can be performed with graduated bougies that are passed over a guidewire. This ensures that the dilator will pass correctly through the stricture (and not into a diverticulum or necrotic tumor, or through the wall of a hiatus hernia). This security exists only if the position of the wire is checked frequently using fluoroscopy or a fixed external landmark. Fluoroscopic monitoring is essential when tight and complex strictures are being treated.

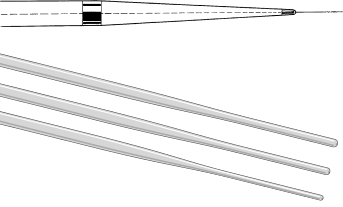

Savary–Gilliard bougies are popular. These are simple tapering plastic wands with radio-opaque markers (Fig 5.2). Variants of this design are available from other manufacturers. Diameters range from 3 to 20 mm.

Fig 5.2 Tips of Savary-Gilliard (above) and American Endoscopy (below) dilators for use over a guidewire.

The following steps should be performed when dilating:

Fig 5.4 Advance the dilator with the left hand and the elbow extended to avoid sudden overinsertion. Keep traction on the wire with the right hand.

Refractory strictures

For some patients, an intensive dilation schedule and maximal gastroesophageal reflux therapy is not adequate to provide symptomatic relief. Several alternative endoscopic techniques have been used for such recalcitrant strictures.

- Corticosteroid injection. The injection of corticosteroids into a stricture is believed to reduce scar formation by preventing collagen deposition and enhancing local breakdown. Before stricture dilation, a standard sclerotherapy injection needle is used to deliver 0.2 mL triamcinolone acetonide into each of the four quadrants of the narrowest area of the stricture. The evidence base for this practice is limited, and small studies have not shown it to be effective in strictures secondary to inflammatory bowel disease.

- Nonmetal stents. Removable nonmetal stents have recently been introduced as an alternative for refractory strictures. Covered self-expanding plastic stents can be effective for benign strictures in the short term, but complications of stent migration and chest pain are common and limit overall clinical success. Biodegradable stents can also be effective in the short term (90 days) but also have high complication rates, and sequential stenting may be required to maintain clinical efficacy.

Post-dilation management

Patients should be kept nil by mouth and under observation for at least 1 hour after dilation. Any complaint of pain should be taken seriously. Chest films and a water-soluble contrast swallow should be performed if there is any suspicion of perforation (perforation is discussed in detail under “Esophageal cancer palliation” below). A trial drink of water is given if progress has been satisfactory. The patient is then discharged with instructions to keep to a soft diet overnight, plus appropriate medications and a follow-up plan. Studies have shown that the use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in patients with benign peptic strictures reduces the need for subsequent dilation when compared with H2 antagonists and should therefore be added after the procedure. Dilation can be repeated within a few days in severe cases, and then subsequently every few weeks until swallowing has been fully restored.

Achalasia

Manometry provides the “gold standard” for the diagnosis of achalasia, but endoscopy is also essential to exclude submucosal or fundal malignancy. Achalasia can be treated with surgical or laparoscopic myotomy, balloon dilation, or with injections of botulinum toxin.

Balloon dilation

Patients with achalasia often have food residue in the esophagus. They should take only a clear liquid diet for several days before the procedure, and large-bore tube lavage may be needed beforehand.

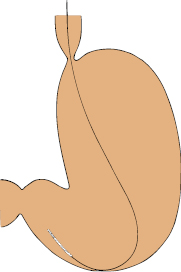

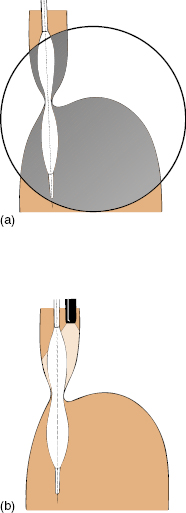

Many different techniques and balloons have been used. The balloon position can be checked radiologically, or under direct vision with the endoscope alongside the balloon shaft (Fig 5.5), or even by a retroversion maneuver with the balloon fitted over the endoscope shaft. We prefer to place a guidewire endoscopically, identify the lower esophageal sphincter fluoroscopically, and then dilate with a balloon under fluoroscopic control.

Fig 5.5 Achalasia dilating balloons (before full inflation). (a) Checked fluoroscopically. (b) Visualized endoscopically.

Achalasia balloons are available with diameters of 30, 35, and 40 mm. It is wise to start with the smallest balloon, warning the patient that repeat treatments may be necessary if symptoms persist or recur quickly.

Inflation is maintained at the recommended pressure for up to 1 minute, and may be repeated. Observe the waist on the balloon fluoroscopically: inadequate expansion may indicate other pathology. Conversely, abrupt disappearance of the waist may suggest perforation (perforation is discussed under “Esophageal cancer palliation” below).

There is usually some blood on the balloon after the procedure. Close observation is mandatory for at least 4 hours. Chest radiographs and a water-soluble contrast swallow are done routinely in some units. Nothing should be given by mouth until the patient and the radiographs have been examined by the endoscopist personally. A trial drink of water is given under supervision. The uncomplicated patient can return to a normal diet on the next day.

Botulinum toxin

Treatment with botulinum toxin can be applied by direct free-hand endoscopic injection into the area of the lower esophageal sphincter, or using endoscopic ultrasound guidance. Reported results are good but short-lived, and the majority of patients require multiple procedures to maintain clinical efficacy. The value of this method may therefore be limited to individuals in whom other procedures are unacceptable or contraindicated.

Esophageal cancer palliation

Barium studies and endoscopy have complementary roles in assessing the site and nature of esophageal neoplasms. Endoscopic ultrasonography is the most accurate staging tool. Endoscopic management can help to improve swallowing in the majority of patients who are unsuitable for surgery because of intercurrent disease or tumor extent. However, endoscopists should be aware of their treatment limitations and should balance technological enthusiasm with full consideration of the patient’s quality of life (and likely duration of survival). Achieving a large lumen will not restore normal swallowing. The goal should be to achieve adequate swallowing at the lowest risk and inconvenience to the patient.

Palliative techniques

Several methods can be used to palliate malignant dysphagia. The abrupt onset of severe dysphagia may be due to the impaction of a food bolus, which can be removed endoscopically by standard techniques. Malignant strictures can be dilated using wire-guided balloons or bougies, taking great care not to split the tumor by being overambitious. The bulk of an exophytic tumor can be reduced by various ablation techniques. Monopolar diathermy is readily available, but it is difficult to control the depth of injury, and charring occurs quickly. Local injection of a toxic agent such as absolute alcohol is also effective, if somewhat unpredictable. Laser ablation (using the Nd:YAG laser) was popular in previous years, largely because a “no-touch” technique seemed esthetically preferable, but the equipment is expensive, and similar results can be achieved using argon plasma coagulation (APC), which is simpler and cheaper. It also has the advantage that the energy can be applied tangentially.

Ablative techniques are most useful in short exophytic lesions, and for recurrences after surgery or stenting. All of the methods are somewhat hazardous (perforation rate up to 5%) and are rarely effective for more than a few weeks. As a result, there is an increasing tendency to place stents as a primary measure. Chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and photodynamic therapy are also used.

Esophageal stenting

There are good indications for using esophageal stents, but insertion can be very challenging, and is not to be undertaken lightly by the endoscopist or patient. The best candidates are mid-esophageal tumors in patients with a prognosis limited to weeks or months, and in those with tracheoesophageal fistulae. Stents cannot be used when the tumor extends to within 2 cm of the cricopharyngeus. They may also function less well in lesions at the cardia because of the angulation, and reflux may be a problem. Newer stents with an antireflux mechanism may theoretically reduce this complication.

Great care must be taken when dysphagia is caused by very large tumors, as stent placement may compromise the airway. Prior bronchoscopy is appropriate in such cases, and trial inflation of a balloon may indicate what diameter is tolerable.

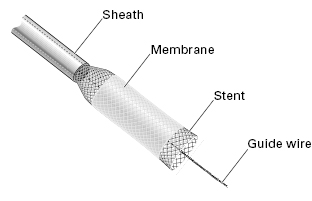

Stent variety

Traditional plastic stents with fixed diameters have largely been replaced by self-expandable metal or plastic stents (SEMS and SEPS, respectively), as they are easier and less hazardous to insert. Many types of SEMS are now available. They vary according to the type, diameter, and weave of the wires (which determine their expansile strength), their shapes and sizes, and the presence or absence of a covering membrane (Fig 5.6). This membrane is helpful in patients with fistulae, and reduces tumor ingrowth, but some mesh must be left exposed to prevent migration. Stents for use in the esophagus have luminal diameters of 15–24 mm, and lengths of 6–15 cm. They are compressed into delivery systems of 6–11 mm. Most expand gradually over a few days, and become fully incorporated in the esophageal wall so that they cannot be removed. Less powerful stents—although easy to place and well tolerated—may not expand sufficiently to relieve the patient’s symptoms, even with balloon dilation.

Newer SEPS are similar to SEMS in concept. The main advantage over metal stents is the ability to be repositioned or removed. Disadvantages include a larger, more difficult delivery system and higher migration rate. Currently, SEPS are indicated for benign esophageal diseases.

Stent insertion

Before insertion the patient should be fully informed about the aims of the procedure, the potential serious risks, and the (few) alternatives. Antibiotic prophylaxis should be considered. The lesion is assessed carefully by radiology and endoscopy, and bougie dilation is performed if necessary (to about 12 mm) to allow passage of the endoscope if possible. The upper and lower margins of the tumor are marked by endoscopic injection of contrast medium using a sclerotherapy needle. A guidewire is placed, and its position checked by fluoroscopy.

The stent system is then introduced over the guidewire and the stent is released by gradual withdrawal of the sleeve. Correct positioning of the stent is judged fluoroscopically (using the contrast medium marks), and then by repeat endoscopy.

Post-stent management

Patients are usually kept in the hospital overnight under observation because of the immediate risk of perforation and bleeding, and for necessary pain control. Chest and water-soluble contrast swallow radiographic studies are performed after about 2 hours. Clear fluids can be given after 4 hours if there have been no adverse developments.

Patients must understand the limitations of the stent, and the need to maintain a soft diet with plenty of fluids during and after meals. Written instructions should be provided and relatives counseled. Overambitious eating or inadequate chewing may result in obstruction. If food impaction occurs, the bolus can usually be removed or fragmented endoscopically using snares, biopsy forceps, or balloons.

Stent dysfunction due to tumor overgrowth can be managed by endoscopic ablation or placement of another stent inside the first. SEPS offer the option of removal. Gastroesophageal reflux can be a problem with stents crossing the cardia. Patients may need to sleep propped up, and to use acid-reducing medications. Occasionally, a good result from chemotherapy or radiotherapy may make it possible to remove a stent. For the same reason, stents (especially the covered variety) may migrate spontaneously. Recovery of stents from the stomach can be challenging.

Esophageal perforation

The endoscopic treatment of esophageal strictures is relatively safe in most cases using optimal techniques. Perforations do occur, however, especially with complex and malignant strictures approached by inexperienced or overconfident endoscopists. The rate is approximately 0.1% in benign esophageal strictures, 1% in achalasia dilation, and 5–10% in treatment of malignant lesions. The risk is minimized by taking the process step by step—gradually and deliberately. Never try to dilate to the largest balloon or bougie simply because it is available.

Early suspicion and recognition of perforation is the key to successful management, and no complaint should be ignored. The problem is usually obvious clinically; the patient is distressed and in pain. Signs of subcutaneous emphysema may develop within a few hours. Radiographic studies should be performed. Surgical consultation is mandatory when perforation is seriously suspected or confirmed. Many confined perforations have been managed conservatively, with nil oral intake, intravenous (IV) fluids, and antibiotics—with or without placement of a sump tube across the perforation.

The choice between surgical and conservative management (and the timing of surgical intervention if conservative management appears to be failing) is often difficult; review of the literature shows varied and strong opinions. Conservative management is more likely to be appropriate when the perforation is in the neck; because the mediastinum is not contaminated, local surgical drainage can be performed simply when necessary. Perforation through a tumor can be treated immediately with a covered stent if the lumen can be found and if surgical cure is not possible.

Gastric and duodenal stenoses

Functionally significant stenoses may occur in the stomach or duodenum as a result of disease (tumors and ulcers) and following surgical intervention (e.g. hiatus hernia repair, gastroenterostomy, pyloroplasty, and gastroplasty). Balloon dilation of stenosed surgical stomas is usually effective (except in the case of banded gastroplasty with a rigid silicone ring). Pyloroduodenal stenosis caused by ulceration can be relieved by balloon dilation, but recurrence is common. Expandable stents are being used with remarkably good effect in patients with malignant stenosis of the stomach and duodenum.

Gastric and duodenal polyps and tumors

Endoscopic polypectomy is frequently used in the colon, and many of the techniques (see Chapter 7) can be applied in the stomach and duodenum. Polyps are much less common in the stomach and duodenum than in the colon, and are rare in the esophagus. Many of these polyps are sessile, and some are largely submucosal, making endoscopic treatment more difficult and hazardous. The possibility of a transmural lesion should be considered, and endoscopic ultrasonography may be helpful in making a treatment decision; surgical (or laparoscopic) resection may be safer. Injecting the base of sessile gastric and duodenal polyps with epinephrine (adrenaline; 1 : 10,000) may make removal easier, and may reduce the risk of bleeding. Some endoscopists use detachable loops for the same purpose.

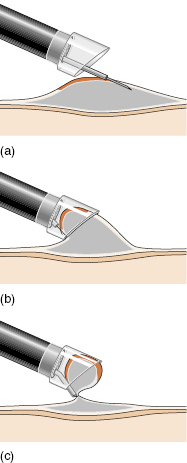

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) has been developed in Japan for removal of sessile lesions up to 2 cm or more in diameter. The lesion is raised up by injecting a cushion of saline/epinephrine, and then sucked into a special transparent plastic cap attached to the tip of the endoscope. The lesion is then resected with a snare loop incorporated in the cap (Fig 5.7).

Fig 5.7 Endoscopic mucosal resection. (a) Inject a saline cushion below the lesion. (b) Suck the lesion into the transparent cap. (c) Snare and resect the lesion.

Snare diathermy techniques can be used also to obtain large biopsy specimens when the gastric mucosa appears thickened, and when standard biopsy techniques have failed to provide a diagnosis.

Gastric polypectomy, EMR, and snare loop biopsy techniques can cause bleeding and perforation. They also leave an ulcer; it is wise to prescribe acid-suppressant medication for a few weeks.

Foreign bodies

Foreign bodies are mainly a problem in children, in elderly patients with poor teeth, and in the drunk or deranged. The problem is obvious if the patient suddenly cannot swallow, and especially if a missing object is visible on a radiograph. However, many instances are less straightforward. Patients may not know that they have swallowed a foreign object. Some common items (e.g. bones and drink-can tags) are not radiopaque. It is therefore necessary to maintain a high index of suspicion.

Chest and abdominal radiographs (with lateral views) are appropriate, as they may identify radiopaque objects or signs of esophageal perforation such as mediastinal or subcutaneous air. A water-soluble contrast swallow examination is helpful in some patients, but it is not necessary, and is potentially hazardous if dysphagia is complete.

Many foreign bodies pass spontaneously, but active treatment should be initiated within hours in some circumstances.

Urgent treatment is required for:

- patients who cannot swallow saliva

- impacted sharp objects

- ingestion of button batteries (which can disintegrate and cause local damage).

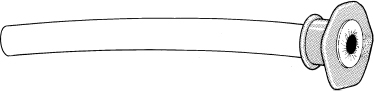

Foreign body extraction

Objects impacted at or above the cricopharyngeus are usually best removed by surgeons with rigid instruments. Flexible endoscopy now takes precedence in most (but not all) other situations. The use of an overtube increases the therapeutic options (Fig 5.8). Endoscopy can usually be accomplished with conscious sedation, but general anesthesia should be considered in children and uncooperative adults, and when there is concern about the airway.