Overall Bottom Line

- HBV infection is a significant global health problem.

- Chronic hepatitis B is a major cause of cirrhosis, fulminant hepatitis and HCC worldwide. Chronic hepatitis B is responsible for over 1 million deaths per year globally.

- HDV is dependent on HBV for its reproduction.

- HDV co-infection is associated with more severe disease with a higher incidence of cirrhosis, hepatic decompensation and HCC compared with those with chronic HBV infection alone.

Section 1: Background

Definition of disease

- Hepatitis B is a 42 nm DNA virus in the Hepadnaviridae family.

Incidence/prevalence

- The burden of chronic HBV infection in the USA is greater among certain populations as a result of earlier age at infection, immune suppression or higher levels of circulating infection. These include persons born in geographic regions with high (>8%) or intermediate (2–7%) prevalence of chronic HBV infection, HIV-positive persons (who might have additional risk factors) and certain adult populations for whom hepatitis B vaccination has been recommended because of behavioral risks (e.g. MSM and people who inject drugs).

- Approximately 5% of the global population is infected with HBV. This translates to over 400 million HBV carriers worldwide.

- It is estimated that 1.4 million people in the USA have chronic hepatitis B with 46 000 documented new HBV infections in 2006.

- Many experts believe that there are two to three times more infected persons in the USA.

Etiology

- HBV is transmitted by vertical transmission (perinatal), or horizontal transmission: percutaneous and mucosal exposure to infectious blood or body fluids, sexual exposure, as well as by close person-to-person contact presumably by open cuts and sores, especially among children in hyperendemic areas. The risk of developing chronic HBV infection after acute exposure ranges from 90% in newborns of HBeAg positive mothers to 25–30% in infants and children under age 5 and to less then 5% in adults.

Pathology/pathogenesis

- After exposure to hepatitis B the virus is transported by the bloodstream to the liver, which is the primary site of HBV replication.

- Acute hepatitis B infection can be self-limited, with elimination of virus from blood and subsequent lasting immunity against reinfection, or it can progress to chronic infection with continuing viral replication in the liver and persistent viremia. Rarely, it can present as fulminant hepatitis.

Section 2: Prevention

Clinical Pearls

- The key to prevention is elimination of further spread of infection.

- Offer hepatitis B vaccination to the entire population. Widespread HBV vaccination efforts have lead to a substantial decline in overall incidence of HBV infection in the USA.

- HBIG and vaccination post-delivery has significantly reduced the risk of perinatal transmission, in countries where it is used. Unfortunately it is not 100% effective, and some experts recommend treatment of pregnant women with high viral loads as a preventative measure.

- Increase screening, diagnosis and linkage to care.

Screening

- Screening strategies to diagnose those with hepatitis B include identifying those at risk for HBV infection. Screening begins with a thorough history and physical examination and serum blood sampling for those identified at risk. The CDC 2008 HBV screening guidelines help identify a high risk population that should be tested for HBV (see http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5708a1.htm):

- Persons born in regions of high and intermediate HBV endemicity (HBsAg prevalence ≥2%).

- USA born persons not vaccinated as infants and whose parents were born in regions of HBsAg incidence ≥8%.

- Persons needing immunosuppressive therapy (chemotherapy, post-transplant or treatment of GI/rheumatic disorders).

- Persons with elevated ALT/AST of unknown etiology.

- Donors of blood, plasma, organs, tissues, or semen.

- Persons who are the sources of blood or body fluids resulting in an exposure that might require post-exposure prophylaxis.

- Household, needle-sharing, or sex contacts of persons know to be HBsAg positive.

- People who inject drugs, men who have sex with men, inmates of correctional facilities, hemodialysis patients, co-infection with HIV and/or HCV.

- All pregnant women, infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers.

- Persons born in regions of high and intermediate HBV endemicity (HBsAg prevalence ≥2%).

Primary/secondary prevention

- Primary prevention is directed at identifying those at high risk for transmission and preventing transmission. (All persons should be given HBV vaccination series.)

- Those with serum markers positive for hepatitis B should be counseled on routes and risk of transmission. Their household members and sexual partners should be tested for hepatitis B and offered vaccination if negative for serologic markers.

- Pregnancy is not a contraindication to HBV vaccination. Limited data suggest that developing fetuses are not at risk for adverse events when hepatitis B vaccine is administered to pregnant women. Available vaccines contain non-infectious HBsAg and should cause no risk of infection to the fetus.

- Pregnant women who are identified as being at risk for HBV infection during pregnancy (e.g. having more than one sex partner during the previous 6 months, been evaluated or treated for an STD, recent or current injection drug use, or having had an HBsAg-positive sex partner) should be vaccinated.

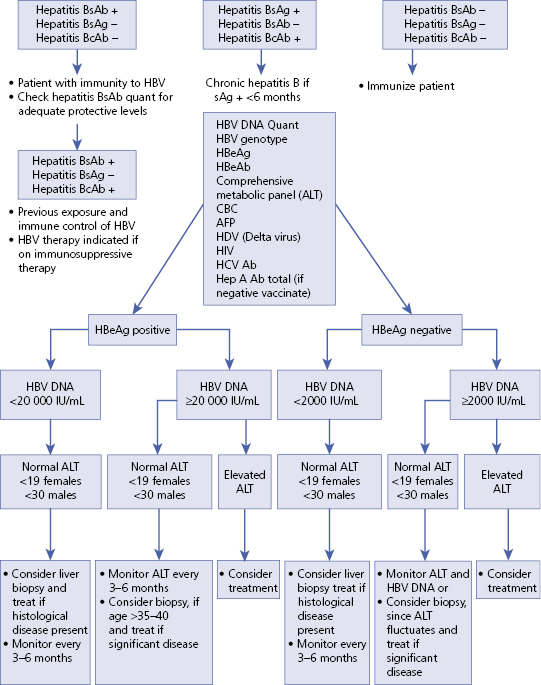

Section 3: Diagnosis (Algorithm 5.1)

– – – – – – – – – –

Algorithm 5.1 Suggested algorithm for patient with serum markers for hepatitis B

EASL HBV guidelines recommend consideration of treatment when HBV DNA levels are above 2000 IU/mL regardless of eAb or eAg markers and/or the serum ALT levels are above the upper limit of normal.

– – – – – – – – – –

Bottom Line

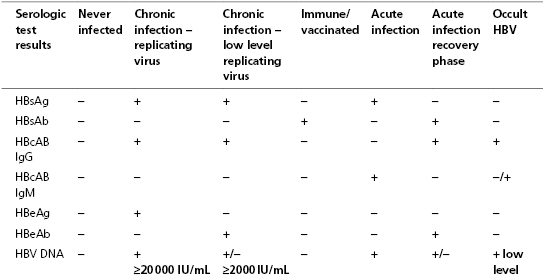

- Serologic markers for HBV infection can help determine acute, chronic or past infection.

- Serologic markers also help identify subjects who are vaccinated or eligible for vaccination.

- With accurate diagnosis of infected individuals educational initiatives can be instituted to prevent further transmission of infection.

Typical presentation

- Persons with chronic HBV infection can be asymptomatic and have no evidence of liver disease, or they can have a spectrum of disease, ranging from chronic hepatitis to cirrhosis or liver cancer.

Clinical diagnosis

Acute HBV

- Illness typically begins 2–3 months after HBV exposure (range: 6 weeks–6 months). Infants, children aged <5 years, and immunosuppressed adults with newly acquired HBV infection typically are asymptomatic; 30–50% of other persons aged ≥5 years have clinical signs or symptoms of acute disease after infection.

- Symptoms of acute hepatitis B include fatigue, poor appetite, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, low-grade fever, jaundice, dark urine, and light stool color.

Chronic HBV

- Infection can be asymptomatic with no evidence of liver disease, or a spectrum of disease can be present, ranging from chronic hepatitis to cirrhosis or liver cancer. Chronic infection is responsible for the majority of cases of HBV-related morbidity and mortality.

- Physical examination may include the appearance of jaundice, liver tenderness and possibly hepatomegaly or splenomegaly. Fatigue and loss of appetite typically precede jaundice by 1–2 weeks. Acute illness typically lasts 2–4 months.

Laboratory diagnosis

List of serum diagnostic tests

- HBcAb IgG – hepatitis B core antibody immunoglobulin G

- HBcAb IgM – hepatitis B core antibody immunoglobulin M

- HBeAb – hepatitis B e antibody

- HBeAg – hepatitis B e antigen

- HBsAb – hepatitis B surface antibody

- HBsAg – hepatitis B surface antigen

- HBV DNA – hepatitis B virus DNA

List of imaging techniques

- The goal of therapy for chronic hepatitis B is to eliminate or significantly suppress the replication of HBV and prevent progression of liver disease to cirrhoisis or HCC eventually leading to death or transplantation.

HCC screening protocol

- AASLD: AFP every 6 months and ultrasound.

- CT and MRI imaging may be preferred by some clinicians (although more expensive they are more sensitive) and in patients who have elevated AFP, cirrhosis or are at high risk for HCC.

- AFP and ultrasound are particularly important for those at high risk:

- Africans >20 years old.

- Asian men >40 years old.

- Asian women >50 years old.

- Family history of HCC.

- Persistently elevated ALT/high viral load in person >40 years old.

- Asians with HBV acquired through vertical transmission.

- Cirrhosis.

- Africans >20 years old.

Potential pitfalls/common errors made regarding diagnosis of disease

- Failure to screen all patients undergoing chemotherapy or other immunosuppressive therapy for HBV leading to serious reactivations and flares.

- Failure to consider HBV DNA levels as the major factor for the risk of disease and categorizing a patient as an “asymptomatic carrier” without checking HBV DNA.

- Failure to realize that laboratory normal ALT is not “healthy ALT” nor is it now part of the guidelines shown in Algorithm 5.1.

- Failure to screen for HCC aggressively enough in high risk patients.

- Failure to consider resistance in the long-term treatment of HBV.

- Lack of consensus between Association guidelines leading to delay in start of treatment.

- Need for frequent monitoring as viral levels fluctuate and disease may progress over time.

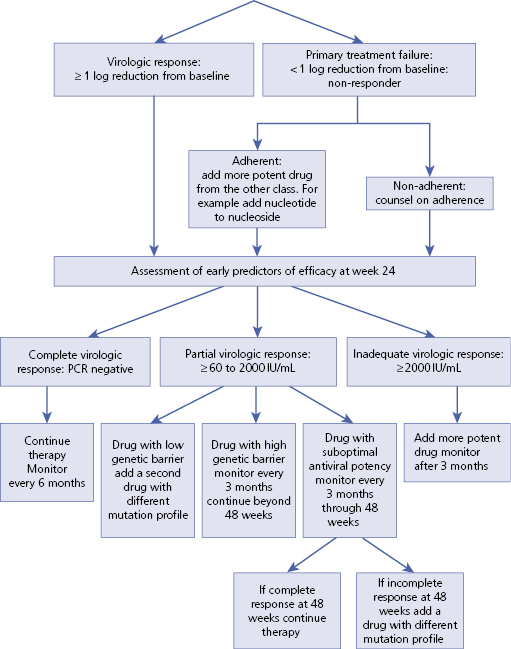

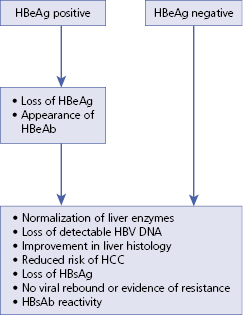

Section 4: Treatment (Algorithm 5.2)

Treatment rationale

- Treatment of chronic hepatitis B is aimed at viral suppression to reduce damage to the liver and its consequences (cirrhosis and HCC) and improve overall survival rate.

- There are seven drugs currently approved by the FDA for treatment of hepatitis B.

FDA approved therapies for HBV

Nucleoside analog

| Immune modulator/antiviral

|

Nucleotide analog

| Demonstrated efficacy not FDA approved

|

- At present, the preferred first-line treatment choices for treatment of naïve patients are entecavir, PEG-IFN-alpha-2a, and tenofovir because of their superior efficacy, tolerability, superior potency and favorable resistance profiles in patients with HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B over comparable drugs in pivotal clinical trials. Treatment with nucleos(t)ide analogs is generally well tolerated and has become the mainstay treatment of chronic HBV infection, resulting in rapid viral suppression, improvement in Child-Pugh scores in patients with cirrhosis, and improved overall survival (Algorithm 5.3). Entecavir should not be used in patients who have previously been treated with lamivudine because of the high rate of resistance associated with its use in that population.

- In HBeAg-positive patients, tenofovir was most effective in inducing undetectable levels of HBV DNA (predicted probability, 88%), normalization of ALT levels (66%), HBeAg seroconversion (20%), and hepatitis B surface antigen loss (5%); it ranked third in histologic improvement of the liver (53%). Entecavir was most effective in improving liver histology (56%), second for inducing undetectable levels of HBV DNA (61%) and normalization of ALT levels (70%), and third in loss of hepatitis B surface antigen (1%). In HBeAg-negative patients, tenofovir was the most effective in inducing undetectable levels of HBV DNA (94%) and improving liver histology (65%); it ranked second for normalization of ALT levels (73%).

– – – – – – – – – –

Algorithm 5.2 Treatment goals for chronic HBV

– – – – – – – – – –

– – – – – – – – – –

Algorithm 5.3 Nucleos(t)ide treatment response