Diagnostic investigation

Laboratory studies

Aminotransferase levels are often mildly elevated but can be normal. Alkaline phosphatase may be elevated in infiltrative tumor of if there is biliary obstruction due to malignancy. In advanced tumors, serum bilirubin may be markedly elevated. Paraneoplastic hypercalcemia and erythrocytosis have been observed. The tumor marker most often associated with hepatocellular carcinoma is α-fetoprotein (AFP), which is a glycosylated protein expressed in proliferating hepatocytes. Although chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis may be associated with levels in the hundreds, levels higher than 400 ng/mL are likely to be caused by hepatocellular carcinoma. An AFP level higher than 1000 ng/mL associated with a liver mass is diagnostic of hepatocellular carcinoma. Unfortunately, AFP is elevated in only 60–70% of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and may be only mildly elevated in certain tumors, which compromises the ability of AFP to serve as a screening test for early hepatocellular carcinoma.

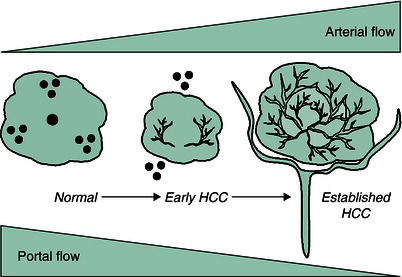

Figure 43.2 Schematic representation of arterialization during hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) development. (Source: Yamada T et al. (eds) Textbook of Clinical Gastroenterology, 5th edn. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2009.)

Imaging studies

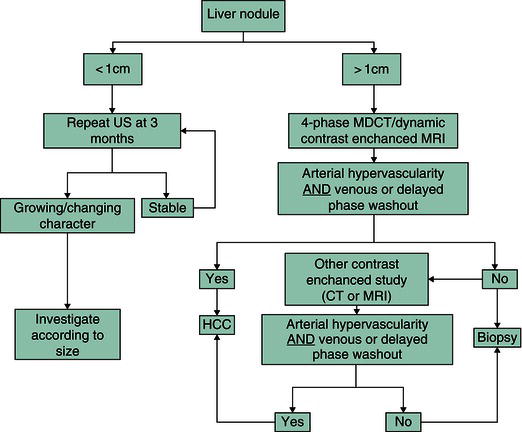

The difficulty in imaging the cirrhotic liver is to distinguish macroregenerative nodules, also known as dysplastic nodules, from hepatocellular carcinoma. The distinguishing feature of HCC is increased arterial vascularity, which results in enhancement on the arterial phase compared with the surrounding normal liver, and “washout” of contrast from the lesion on the portal venous and delayed phases, unlike the surrounding liver tissue (Figure 43.2). For lesions >2 cm in size, this enhancement pattern is associated with a 98% specificity for the diagnosis of HCC, and liver biopsy is not required (Figure 43.3).

Management

The safety, tolerability, and outcome of hepatocellular carcinoma treatment is dependent on the severity of the underlying liver disease, tumor characteristics such as size and vascular invasion, the patient’s performance status, and the efficacy of the treatment intervention.

Figure 43.3 Diagnostic algorithm for suspected HCC. CT, computed tomography; MDCT, multidetector CT; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; US, ultrasound.(Source: Bruix J, Sherman M.Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update.Hepatology 2011;53:1020–1022. Copyright © 2011 American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.)

Surgical resection

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree