Overall Bottom Line

- HAV is an RNA picornavirus that infects only primates. HEV is an RNA virus and a member of the Hepeviridae family that infects humans and multiple domestic (e.g. pigs) animals and small mammals (e.g. rats).

- The route of transmission for HAV and HEV is fecal–oral and both are therefore highly endemic in developing nations with poor sanitation.

- The incubation period for HAV and HEV ranges from 15 to 50 days.

- Clinical features of acute HAV and HEV infection range from asymptomatic to fulminant hepatic failure; presence and severity of symptoms is related to the patient’s age.

- Diagnosis of HAV or HEV infection is made with HAV or HEV IgM antibody.

- Treatment of hepatitis A or E is supportive.

- HEV can cause chronic hepatitis in immuncompromised patients (particularly after liver transplant) and has a high mortality in pregnant women in the third trimester (20%).

Section 1: Background

Definition of disease

- Hepatitis A is an acute infection caused by HAV.

Incidence/prevalence

- An estimated 1.4 million cases of acute hepatitis A occur worldwide annually.

- HAV infections occur sporadically and via outbreaks or epidemics.

- Hepatitis A is highly endemic in developing nations with poor sanitation, where infection often occurs in children, who are likely to be asymptomatic. Because even asymptomatic infected children may shed virus in their stools for up to 6 months, infection in children often initiates and perpetuates community-wide outbreaks. The prevalence of HEV is about 3 million acute cases annually.

Economic impact

- Acute HAV/HEV infections can occur as large epidemics related to contaminated food or water with significant economic and social impact on communities.

Etiology

- HAV is a non-enveloped RNA picornavirus that infects only primates.

- There are five different HAV genotypes.

- HEV is a small (7.2 kb) non-enveloped positive sense, single-stranded RNA with five identified genotypes

Pathology/pathogenesis

- The pathology and pathogenesis of HAV and HEV are very similar.

- The route of transmission is oral inoculation of fecally excreted virus by person-to-person contact. The virus is ingested, traverses the small intestine and reaches the liver via the portal circulation and replicates within the liver in hepatocytes.

- After replication, mature virus reaches the systemic circulation and is released into the biliary tree and subsequently passes into the small intestine and is eventually excreted in the feces.

- Chronic shedding of HAV/HEV in feces does not occur.

- Viremia occurs soon after infection and persists through the period of liver enzyme elevation.

- On rare occasions, HAV/HEV has been transmitted by transfusion of blood products collected during the donor’s viremic phase.

- The peak infectivity correlates with the greatest viral excretion in the stool during the 2 weeks before the onset of jaundice or elevation of liver enzyme levels.

- Liver inflammation is due to the host’s cell-mediated immune response. HAV-specific CD8+ lymphocytes and natural killer cells induce liver cell death and apoptosis.

Predictive/risk factors

- Living in areas with poor sanitation.

- Children > adults.

- Not previously vaccinated against HAV.

- Intravenous drug use.

- Household contact with infected person.

- Sexual partner of someone with acute HAV infection.

- Travel to endemic areas.

- Men who have sex with men.

- HIV-positive patients.

Section 2: Prevention

Clinical Pearls

- Most effective prevention strategies include hepatitis A immunization and improved sanitation. A preventive vaccine for HEV has recently been developed and used in China.

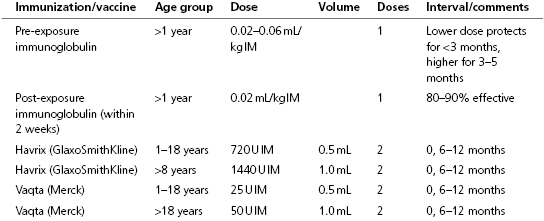

- A combination vaccine (Twinrix, GlaxoSmithKline) is available for HAV and hepatitis B vaccination in adults. It contains half the adult Havrix dose and 20 μg of recombinant hepatitis B surface antigen protein and is given in three doses at 0, 1, 6 months.

Screening

- No routine screening.

Primary prevention

- Most effective prevention strategies include hepatitis A immunization and improved sanitation.

- Personal hygiene practices, such as regular hand-washing, reduce the spread of HAV/HEV.

- HAV vaccination consists of two doses to ensure long-term protection. Nearly 100% of people will develop protective levels of antibodies to the virus within one month after a single dose of the vaccine.

- Adequate supplies of safe-drinking water and proper disposal of sewage within communities, combined with personal hygiene practices, such as regular hand-washing, reduce the spread of HAV/HEV.

Secondary prevention

- Primary contacts of persons infected with HAV should receive immune globulin administered intramuscularly which provides short-term protection (i.e. 3–5 months) through passive transfer of hepatitis A virus antibody. Immune globulin should be administered within 2 weeks after exposure for maximum protection. There is no evidence that immunoglobulin provides protection against HEV (even if the immunoglobulin is produced in countries where HEV is endemic).

- Even after virus exposure, one dose of the vaccine within two weeks of contact with the virus has protective effects.

Section 3: Diagnosis

Clinical Pearls

- Hepatitis A and E range from asymptomatic to mild or severe disease. Symptoms and signs can include fever, malaise, loss of appetite, diarrhea, nausea, abdominal discomfort, dark-colored urine and jaundice. Physical signs can include tender hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, bradycardia, and posterior cervical lymphadenopathy.

- The icteric phase, which lasts 4–30 days, begins with hyperbilirubinuria followed within a few days by pale, clay-colored stools and jaundice.

- The anti-HAV or anti-HEV IgM test is the preferred confirmatory test for acute hepatitis A or E. HAV/HEV IgM usually remains positive for approximately 4 months but can occasionally be present for up to 1 year.

Differential diagnosis

| Differential diagnosis | Features |

|---|---|

| Viral (HBV or HCV)/infectious | Evidence of serologic markers or viremia, consistent with other viral liver disease Liver biopsy evidence of periportal, not pericentral, mononuclear leukocyte infiltration |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | Presence of serum autoimmune markers and elevated gamma globulin Liver biopsy with plasma cell infiltration and immune cells, interface hepatitis (occasionally plasma cells may predominate in hepatitis A) |

| Biliary obstruction | Acute obstruction can lead to cholestatic liver tests abnormalities Imaging to evaluate for the presence and cause of biliary obstruction including ultrasound, EUS, MRI/MRCP, ERCP |

| Metabolic liver diseases | Wilson disease: evidence of serum/urine copper abnormalities, low AP Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency: genetic testing |

| Vascular disorders of liver | Imaging to assess vasculature |

| Alcoholic hepatitis | Evidence of leukocytosis, elevated liver tests Liver biopsy with features of alcohol steatohepatitis |

| DILI | Diagnosis of exclusion and culprit drug |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree