Pathogenesis

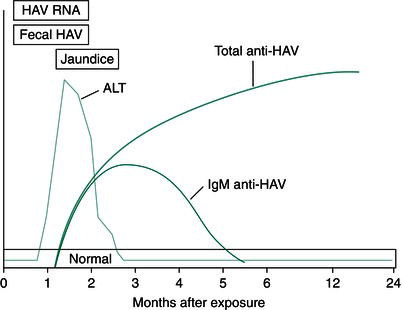

Hepatitis A virus is an RNA virus that produces hepatocellular injury by mechanisms that remain poorly understood. Both direct cytopathic and immunologically mediated injury seem probable but neither has been proven. After exposure, there is a 2–6-week incubation period before symptom onset, although the virus may be detectable in the stool 1 week before clinically apparent illness. The immune response to HAV begins early and may contribute to hepatocellular injury. Immunological clearance of HAV is the rule and unlike hepatitis viruses B and C, HAV never enters a chronic phase. By the time symptoms are manifest, patients invariably have IgM antibodies to HAV (anti-HAV IgM), which typically persist for 3–6 months. IgG antibodies to HAV (anti-HAV IgG) also develop and provide life-long immunity against reinfection.

Clinical course

Many patients with HAV infection, in particular 80–90% of children, are asymptomatic. Only 5–10% of patients with serological evidence of prior HAV infection recall an episode of jaundice. Factors that contribute to subclinical versus clinical infection remain unclear.

The syndrome of acute hepatitis caused by HAV is clinically indistinguishable from other viral causes of acute hepatitis. Patients usually present with a nonspecific prodrome of fatigue, anorexia, nausea, headache, myalgias, and arthralgias. This may be followed by jaundice and right upper quadrant pain. Some patients may experience pruritus but this rarely requires treatment. Vomiting is common and may lead to fluid and electrolyte imbalance. Physical signs include icterus and tender hepatomegaly. The spleen is palpable in a minority of patients. A prolonged form of HAV infection is characterized by pruritus, fever, weight loss, serum bilirubin >10 mg/dL and a clinical course lasting a minimum of 12 weeks. It is seen more often in older individuals. A relapsing variant characterized by initial clinical improvement followed by recrudescent symptoms 5–10 weeks after recovery affects 20% of patients, and the clinical course is rarely protracted, lasting no longer than 12 weeks. Resolution of HAV infection with complete recovery, except in the rare cases of fulminant hepatitis (~1%), is the rule.

Diagnostic and serological studies

Elevations in levels of aminotransferases usually occur 1–2 weeks before the onset of symptoms and persist for up to 4–6 weeks. The alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level usually is higher than the aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level; absolute values often exceed 1000 IU/L. The level of enzyme elevation does not correlate with disease severity. Asymptomatic cases may have serum AST or ALT levels in the thousands. Serum bilirubin levels usually peak 1–2 weeks after symptoms appear but they rarely exceed 15–20 mg/dL. HAV infection occasionally produces a cholestatic pattern of liver biochemical abnormalities with a disproportionate elevation in the alkaline phosphatase level. Other laboratory abnormalities include relative lymphocytosis with a normal total leukocyte count.

Diagnosis relies on detecting anti-HAV IgM in the serum. Because this IgM component of the humoral immune response lasts only 3–6 months, its presence implies recent or ongoing infection (Figure 37.1). Liver biopsy is not necessary if the findings from serological testing are positive and is performed only if the diagnosis is in doubt. Although there are no distinguishing features of any form of viral hepatitis, patchy necrosis and lobular lymphocytic infiltrates are typical findings. Occasionally, ultrasound scanning may be necessary to exclude biliary obstruction, particularly in patients with the cholestatic variant of HAV infection. This test may confirm hepatomegaly and reveal an inhomogeneous liver parenchyma but findings usually are nonspecific.

Management

Hepatitis A virus is self-limited, and symptoms resolve in most cases over the course of 2–4 weeks. There is no specific treatment, and patients should be encouraged to maintain fluid and nutritional intake. Ten percent of patients require hospitalization for intractable vomiting, worsening laboratory values, or comorbid illnesses. The overall mortality rate for hospitalized patients is less than 1%. Deaths are mainly the result of the rare case of fulminant hepatitis, which is characterized by signs of hepatic failure, including encephalopathy. These patients are typically older and may have chronic hepatitis C infection, and should be referred to liver transplant centers for management and potential transplantation.

Figure 37.1 Typical serological course of acute hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection. ALT, alanine aminotransferase; IgM, immunoglobin M. (Source: Yamada T et al. (eds) Textbook of Gastroenterology, 5th edn. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2009.)

Prevention

Infection with HAV can be prevented by either passive or active immunization. Patients exposed to feces of HAV-infected individuals should be given immunoglobulin (0.02 mL/kg) within 2 weeks of exposure. Travelers to endemic areas may be given immunoglobulin, which provides protection for about 3 months, or the formalin-inactivated hepatitis A vaccine, which provides long-term immunity to more than 90% of persons, beginning 1 month after the first dose of the two-dose regimen.

Hepatitis B

Epidemiology

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is an important cause of acute and chronic hepatitis. In regions of Africa, Asia, and the Mediterranean basin where HBV is endemic, there are high rates of chronic HBV infection. Worldwide, there are 400 million HBV carriers. In the United States during the 1990s, HBV accounted for more than 175,000 cases of acute hepatitis annually, and 5% of these entered a chronic phase. In contrast, perinatal transmission of HBV leads to chronic HBV infection in more than 90% of cases. About 0.3% of the population in the United States suffers chronic infection with HBV. Although 30–50% of infections with HBV have no identifiable source, the main route of transmission is percutaneous. The most common means of transmission are sexual contact with an infected individual, intravenous drug use, and vertical transmission from mother to child. Several epidemiological surveys have emphasized the importance of contact transmission among individuals in the same household, even in the absence of intimate or sexual contact. The mechanism of this contact-associated transmission remains poorly defined. Blood transfusion is an unlikely source of HBV in western countries with the use of blood bank screening but poses a major risk in developing countries that do not screen blood or blood products for HBV.

Pathogenesis

Hepatitis B virus is a DNA virus that has seven genotypes, A–G, based on differences in sequence. One component of HBV is an envelope that contains a protein called hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). Inside the envelope is a nucleocapsid that contains the hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg), which is not detectable in serum. During viral replication, a third antigen, termed the hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), and HBV DNA are detectable in the serum. While in the replicative phase, HBV produces hepatocellular injury primarily by activating the cellular immune system in response to viral antigens on the surface of hepatocytes. The vigor of the immune response determines the severity of acute HBV hepatitis and the probability that the infection will enter a chronic phase. An exuberant response can produce fulminant hepatic failure, whereas a lesser response may fail to clear the virus.

After exposure to HBV, there is an incubation period of several weeks to 6 months before the onset of symptoms. HBsAg appears in the serum, followed shortly by HBeAg late in the incubation period. Detectable levels of HBeAg correlate with active viral replication, as does the quantity of HBV DNA. The first detectable immune response is antibody to HBcAg (anti-HBc), which is usually present by the time symptoms occur. As with HAV, the initial antibody response is primarily IgM, which persists for 4–6 months and is followed by a life-long IgG response. Antibodies to HBsAg (anti-HBs) develop in more than 90% of adult individuals with acute hepatitis. The appearance of anti-HBs, usually several weeks after the disappearance of HBsAg and resolution of symptoms, signifies recovery. Anti-HBs provides life-long immunity to reinfection, although titers may decrease to undetectable levels over the course of years.

Antibodies to HBeAg (anti-HBe) appear earlier than anti-HBs and usually signify the clearance of HBeAg and cessation of replication. In chronic HBV infection, the virus may be in a replicative phase characterized by the presence of HBsAg, HBeAg, and high levels of HBV DNA, along with an immune-mediated chronic inflammatory response. Alternatively, HBV may enter a nonreplicative state, formerly referred to as the carrier state, in which HBV is maintained by insertion into the host genome. In this phase, HBsAg persists but HBeAg disappears and anti-HBe appears. HBV DNA is present at low levels (fewer than 100,000 copies/mL). The inflammatory response in this nonreplicative state usually is minimal but due to integrated HBV DNA in the hepatocytes, the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma persists

Clinical course

Most acute HBV infections are asymptomatic, especially if acquired at a young age when chronicity is more likely. Thirty percent of infections with HBV in adults result in acute hepatitis, which is indistinguishable from other forms of acute viral hepatitis. The illness usually has a 1–6-month incubation period. Hepatitis may be preceded by a serum sickness syndrome characterized by fever, urticaria, arthralgias, and, rarely, arthritis. This syndrome is probably caused by immune complexes of HBV antigens and antibodies, which may also produce glomerulonephritis and vasculitis (including polyarteritis nodosa) in patients with chronic HBV infection. Patients with chronic HBV infection may have a history of a distant bout of acute hepatitis but a history of jaundice is unusual. Most patients with chronic HBV infection remain asymptomatic for years. When symptoms develop, they usually are nonspecific, including malaise, fatigue, and anorexia. Some patients exhibit jaundice and complications of portal hypertension, such as ascites, variceal hemorrhage, or encephalopathy. Physical examination in the chronic phase may be normal. Some patients may present with stigmata of cirrhosis and portal hypertension, including ascites, dilated abdominal veins, gynecomastia, and spider angiomata.

Diagnostic and serological studies

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree