Overall Bottom Line

- Diagnosis of ALF in children is more complex than in adults, as encephalopathy may be subtle, appear late and may even remain unrecognized.

- History is usually taken from the family in younger children and should focus on age of presentation (neonate, toddler, adolescent), family history and consanguinity, perinatal course, newborn screen results, growth and development, feeding (breast milk, fructose), episodes of fasting, school performance, available drugs and over-the-counter medications.

- The most common etiology for ALF in children in the Western world remains indeterminate (non-A-E hepatitis) and is a diagnosis of exclusion.

- Children with ALF should be referred to a pediatric liver transplant center. Children with encephalopathy or an INR >4 (without encephalopathy) should be admitted to an ICU for continuous monitoring.

- In neonatal liver failure, IV acyclovir should be started at the earliest opportunity, while awaiting definitive diagnosis. Specific therapies are available for HSV, acetaminophen overdose, several metabolic diseases, neonatal hemochromatosis, hemophagocytic syndrome, Wilson disease and AIH.

- Liver transplantation remains the definitive treatment with utility of reduced (split) and living donor grafts to increase the donor pool.

Section 1: Background

Definition

- The definition of ALF in children is more complex than in adults – encephalopathy may be subtle, appear late and may even remain unrecognized.

- A practical definition of ALF suggested by the PALF study group is “coagulopathy with INR of ≥1.5 with encephalopathy or INR ≥2 without encephalopathy due to a liver cause, not correctable by intravenous vitamin K,” with biochemical evidence of acute liver injury and no evidence of chronic liver disease.

Disease classification

- The 1993 classification defines hyperacute, acute and subacute liver failure as coagulopathy and encephalopathy developing within 1 week, 8–28 days and 4–12 weeks within onset of jaundice.

Incidence and prevalence

- A USA population-based surveillance for ALF conducted in 2007 showed an annual incidence of 5.5 per million among all ages.

- The exact frequency of ALF in children is unknown.

Etiologies of ALF in children

- The etiology for ALF in children differs from adults and varies by age and geography (in the developing world, hepatitis A and other infections are more common).

- The most common etiology for ALF in children in the Western world remains indeterminate (non-A-E hepatitis) and is a diagnosis of exclusion.

- In children 0–3 years: indeterminate 54%, metabolic 15% (tyrosinemia, galactosemia, hereditary fructose intolerance), viral 8% (HSV, echovirus, adenovirus, HBV), ischemia 4% (congenital heart disease, cardiac surgery, myocarditis, severe asphyxia), autoimmune 4%, acetaminophen 3% and other 12% (neonatal hemochromatosis, sepsis, medications [valproate, isoniazid], hemophagocytic syndrome).

- HBV is less common in children as a cause for ALF. Infants born to mothers who have active hepatitis and are HBeAg negative are at risk for ALF presenting around 3 weeks to 3 months of age.

- In children 3–18 years: indeterminate 47%, acetaminophen 18%, autoimmune 8% (mostly LKM positive, type 2), metabolic 7% (Wilson disease), drugs 6%, viral 4%, ischemia 4% (Budd–Chiari syndrome), and other 6% (including malignancy and hyperthermia).

Pathology/pathogenesis

- The mechanisms that underlie the poor regenerative response in ALF are not well defined. Massive destruction of hepatocytes may represent a direct cytotoxic effect (virus), accumulation of potentially hepatotoxic metabolites (drugs, inborn errors of metabolism) or oxidative damage (Wilson disease or neonatal hemochromatosis).

- Patchy or confluent, massive necrosis of hepatocytes is commonly found on liver biopsy or explant. Centrilobular necrosis is found in acetaminophen intoxication or circulatory shock and microvesicular fatty change of hepatocytes in inborn errors of metabolism and valproate hepatotoxicity. Hepatocyte death may occur predominantly by apoptosis rather than by necrosis in some metabolic disorders. Liver biopsy is rarely helpful in ALF and is usually contraindicated because of the presence of coagulopathy.

- Children who develop ALF may have an underlying altered immune response that increases the risk of ALF and infections.

Predictive/risk factors

- The prognosis is dependent on the etiology.

- Poor prognostic factors:

- INR >4: 73% of children with an INR <4 surviving without OLT compared with 16.6% with an INR >4.

- Grade 3–4 encephalopathy.

- Factor V concentration <25%.

- Metabolic acidosis with arterial pH <7.3 after the second day of acetaminophen overdose in adequately hydrated patients is associated with 90% transplant free mortality.

- Hepatorenal syndrome.

- Jaundice for more than 7 days prior to the onset of encephalopathy.

- ALF in Wilson disease, non-acetaminophen drug-induced ALF, indeterminate (non-A-E) hepatitis and AIH with encephalopathy.

- A prognostic score is available predicting the outcome of decompensated Wilson disease, incorporating bilirubin, INR, AST, WBC, and albumin at presentation.

- INR >4: 73% of children with an INR <4 surviving without OLT compared with 16.6% with an INR >4.

Section 2: Prevention

Not applicable for this topic.

Section 3: Diagnosis

Bottom Line

- History is usually taken from the family in younger children and should focus on age of presentation (neonate, toddler, adolescent), family history and consanguinity, perinatal course, newborn screen results, growth and development, feeding (breast milk (lactose), fructose), episodes of fasting, school performance, available drugs and over-the-counter medications.

- Physical examination is similar to adults. However, encephalopathy may be subtle and special attention given to dysmorphic features (genetic disease) and growth and development.

- Laboratory tests should include blood glucose (particularly in infants), electrolytes, INR and daily CBC with surveillance blood and urine cultures. For testing for etiology see Algorithm 34.1.

- Liver biopsy is rarely helpful and usually contraindicated due to coagulopathy.

– – – – – – – – – –

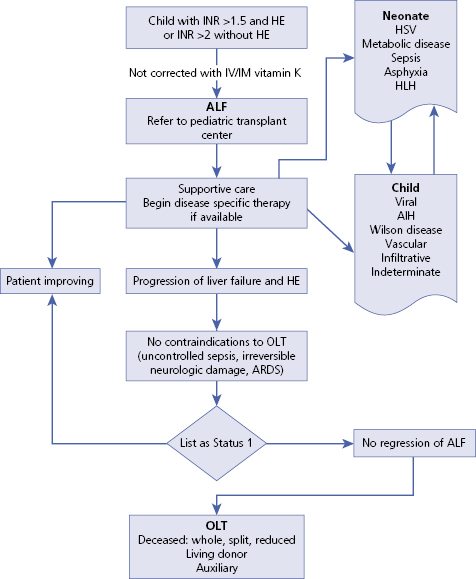

Algorithm 34.1 Diagnosis of acute liver failure in children

– – – – – – – – – –

Differential diagnosis

- Other causes of coagulopathy in the presence of liver disease should be considered.

| Differential diagnosis | Features |

|---|---|

| Vitamin K deficiency | History of cholestasis or biliary obstruction Factors II, VII, IX, X low Factor V (not vitamin K dependent) and factor VIII (extrahepatic production) are normal |

| Sepsis | Fever, other signs and symptoms of infection (cardiovascular, etc.) Elevated fibrinogen split products Low fibrinogen and platelets All factors (II, V, VII, VIII, IX, X) low as consumption coagulopathy |

| Chronic liver disease | Onset of jaundice >8 weeks Other signs and symptoms of chronic liver disease and portal hypertension: ascites, splenomegaly, growth failure, caput medusae, clubbing |

Typical presentation

- The child with fulminant hepatic failure usually has been previously healthy. Progressive jaundice, anorexia, vomiting and abdominal pain are commonly observed. Hepatic encephalopathy may be initially characterized by irritability, poor feeding, and a change in sleep rhythm in infants and disturbances of consciousness or motor functioning in older children.

- Progression can occur over the course of a few days or weeks.

- Bleeding from the GI tract and easy bruising, as a result of severe coagulopathy.

Clinical diagnosis

History

- History is usually taken from the family in younger children and should focus on age of presentation (neonate, toddler, adolescent), family history (liver disease, miscarriages or neonatal deaths) and consanguinity, antenatal and perinatal course, newborn screen results, growth and development, feeding (breast milk, lactose, fructose), episodes of fasting, sick contacts, constitutional symptoms, fever, fatigue, abdominal pain, progression of jaundice, vomiting and diarrhea, rashes, other comorbidities (autoimmune disease), school performance and medications.

- For acetaminophen: careful review of dose and frequency should be taken, including other remedies that may contain acetaminophen (i.e. cough medicine).

- Over-the-counter medications should be investigated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree