Gallstones

Choledocholithiasis

Biliary sludge

Microlithiasis

Mechanical/structural injury

Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction

Pancreas divisum

Trauma

Following endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

Pancreatic malignancy

Peptic ulcer disease

Inflammatory bowel disease

Medications

Azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine

Dideoxyinosine

Pentamidine

Sulfonamides

L-Asparaginase

Thiazide diuretics

Metabolic

Hyperlipidemia

Hypercalcemia

Infectious

Viral

Bacterial

Parasitic

Vascular

Vasculitis

Atherosclerosis

Genetic mutations

Cationic trypsinogen (hereditary) (serine protease-1, PRSS1)

Serine protease inhibitor, Kazal-type 1 (SPINK1)

Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR)

Miscellaneous

Scorpion bite

Idiopathic pancreatitis

Cystic fibrosis

Coronary bypass

Tropical pancreatitis

Diagnostic investigation

Laboratory studies

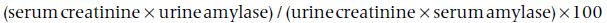

Elevated serum amylase and lipase levels are the most common abnormalities seen in laboratory studies of patients with acute pancreatitis and result from increased release and decreased renal clearance of the enzymes. Elevations greater than fivefold are virtually diagnostic of pancreatitis but disease severity does not correlate with the degree of enzyme elevation. Total serum amylase is composed of pancreatic and salivary isoforms. Salivary amylase levels increase with salivary gland disease, chronic alcoholism without pancreatitis, cigarette smoking, anorexia nervosa, esophageal perforation, and several malignancies. The pancreatic amylase isoform may also be elevated in cholecystitis, intestinal perforation, renal failure, and intestinal ischemia. Five percent to 10% of episodes of acute pancreatitis produce no increases in serum amylase and lipase levels, which are most common in underlying chronic alcoholic pancreatitis, long-term glandular destruction, and fibrosis with loss of functional acinar tissue. Hyperamylasemia has been reported in up to 40% of patients with AIDS yet clinical disease occurs in less than 10%. Macroamylasemia is characterized by persistent elevation of serum amylase levels because of decreased renal excretion of a high molecular weight macroamylase. The disorder is benign. Differentiation from pathological hyperamylasemia relies on calculating the amylase-to-creatinine clearance ratio (ACCR):

An ACCR less than 1% suggests macroamylasemia.

Serum lipase is reportedly a more specific marker of pancreatitis but mild elevations are observed in other conditions (e.g. renal failure and intestinal perforation). In pancreatitis, lipase levels may remain elevated for several days after amylase levels have normalized. Therefore, if the diagnosis is delayed, hyperlipasemia may be the only abnormal laboratory finding. A lipase-to-amylase ratio higher than 2 is reportedly specific for alcoholic pancreatitis; however, this should not replace the history and physical examination as the primary means for discerning the cause of pancreatitis.

Patients often have other laboratory abnormalities. Leukocytosis can result from inflammation or infection. An increased hematocrit may signal decreased plasma volume caused by extravasation of fluid; a decreased hematocrit may be caused by retroperitoneal hemorrhage. Pancreatic necrosis develops in about half of the patients whose hematocrit is higher than 44% when admitted to the hospital or if the hematocrit fails to decrease 24 h after admission. Electrolyte disorders are common, particularly hypocalcemia, which in part is caused by sequestration of calcium salts as saponified fats in the peripancreatic bed. Patients with underlying liver disease or choledocholithiasis may have abnormal liver chemistry levels. Bilirubin levels higher than 3 mg/dL suggest a biliary cause of pancreatitis.

Imaging studies

Ultrasound is the most sensitive noninvasive means for detecting gallstones, biliary tract dilation, and gallbladder sludge. Intralumenal gas may obscure images of the pancreas in 30–40% of patients, making ultrasound an insensitive technique for detecting the changes associated with pancreatitis. Computed tomographic (CT) scanning is superior to ultrasound for imaging the peripancreatic bed. In mild cases, the pancreas may appear edematous or enlarged. More severe inflammation may extend into surrounding fat planes, producing a pattern of peripancreatic fat stranding. CT scanning also is optimal for defining inhomogeneous pancreatic phlegmons with ill-defined margins or well-defined pseudocysts. A dynamic arterial phase CT scan can identify areas of tissue necrosis, which are at risk of subsequent infection. The magnitude of pancreatic necrosis predicts the prognosis. Given its high cost and the limited yield in evaluating mild disease, CT scanning should be reserved for patients with severe disease. Once pancreatitis has resolved, CT scanning may have a role in excluding pancreatic cancer as a cause of pancreatitis in older patients. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, which is considerably more expensive than ultrasound or CT scanning, has a sensitivity higher than 90% for detecting bile duct stones. Endoscopic ultrasound is a sensitive test for detecting persistent biliary stones and can be used to distinguish patients who may benefit from treatment with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Endoscopic ultrasound also is useful for detecting small pancreatic or ampullary tumors, pancreas divisum, and chronic pancreatitis.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography is primarily a therapeutic tool in acute biliary pancreatitis; it has no role in diagnosing acute pancreatitis. After an acute attack has resolved, ERCP should be considered if the cause of the pancreatitis is unclear.

Management

Prognosis

The most common prognostic criteria used to assess acute pancreatitis are the Ranson criteria, which are observations made at admission and at 48 h after admission, and the simplified Glasgow criteria, which are variables measured at any time during the first 48 h after admission (Table 32.2). The prognostic accuracy of the two scales is similar. Although the Ranson criteria were developed to assess alcoholic pancreatitis, they are frequently applied to pancreatitis from other causes. If two signs or fewer are present, mortality is less than 1%; three to five signs predict a mortality rate of 5%; and six or more signs increase the mortality rate to 20%. Other factors associated with a poor prognosis include obesity and extensive pancreatic necrosis. A CT-based scoring system, measurement of serum levels of the trypsinogen activation peptide, and the APACHE II score have also been used to assess the severity of acute pancreatic damage.

Complications

Patients with severe pancreatitis may develop peripancreatic fluid collections or pancreatic necrosis; either can become infected. The role of prophylactic antibiotics in patients with severe pancreatitis is controversial, although two meta-analyses have concluded that prophylaxis decreases sepsis and mortality in patients with necrosis. If administered, imipenem-cilastatin, cefuroxime, and a combination of a quinolone with metronidazole are most effective for preventing infectious complications. Infections in the first 1–2 weeks usually involve peripancreatic fluid collections or pancreatic necrosis and are characterized by florid symptoms. More indolent courses are characteristic of pancreatic abscesses, which can arise several weeks after a bout of pancreatitis in well-defined pseudocysts or areas of resolving pancreatic necrosis. Gram stain and culture of fluid obtained by CT-guided aspiration is mandatory if infection is suspected. Polymicrobial, Gram-negative enteric bacteria, and anaerobic organisms are most often identified. Infected necrotic tissue and pancreatic abscesses require immediate surgical debridement, although some well-defined abscesses may be drained percutaneously. Sterile pancreatic necrosis should be managed with supportive medical care unless symptomatic or if significant clinical deterioration occurs.

Table 32.2 Prognostic criteria for acute pancreatitis

Adapted from Agarwal N, Pitchumoni CS, Sivaprasad AV. Evaluating tests for acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 1990;85:356, and Marshall JB. Acute pancreatitis: a review with an emphasis on new developments. Arch Intern Med 1993;153:1185.

| Ranson criteria | Simplified Glasgow criteria |

| At admission | Within 48 h of admission |

| Age >55 | Age >55 |

| Leukocyte count >16,000/μL | Leukocyte count >15,000/μL |

| Lactate dehydrogenase >350 IU/L | Lactate dehydrogenase >600 IU/L |

| Glucose >200 mg/dL | Glucose >180 mg/dL |

| Aspartate aminotransferase >250 IU/L | Albumin <3.2 g/dL |

| Calcium <8 mg/dL | |

| Arterial PO2 <60 mmHg | |

| Serum urea nitrogen >45 mg/dL | |

| 48 h after admission Hematocrit decrease >10% Serum urea nitrogen increase >5 mg/dL Calcium <8 mg/dL Arterial PO2 <60 mmHg Base deficit >4 meq/L Estimated fluid sequestration >6 L |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree