Tubular

Tubulovillous

Villous

Low-grade dysplasia

High-grade dysplasia (intraepithelial carcinoma)

Serrated

Hyperplastic

Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis

Colitis cystica profunda

Lipoma

Carcinoid

Metastatic lesions

Hemangioma

Fibroma

Endometriosis

Leiomyoma

Carcinomatous or malignant polyp

Juvenile

Peutz–Jeghers

Although colonic adenomas are premalignant lesions, the proportion that progresses to adenocarcinoma is unknown. Older literature reporting the long-term follow-up of patients with polyps that had been identified but not removed suggested that the risk of developing adenocarcinoma from a 1 cm polyp was 3% at 5 years, 8% at 10 years, and 24% at 20 years after diagnosis. Both the rate of growth and the malignant potential of individual polyps vary substantially. Serial examinations over several years illustrate that many polyps remain stable or even regress. The difference between the mean age at diagnosis of colonic adenoma and at diagnosis of adenocarcinoma leads to an estimate of the mean time of progression from adenoma to colorectal cancer of about 7 years. Since the lifetime cumulative incidence of colorectal cancer is about 4–6% in western countries, it is estimated that only about 1 in 20 adenomas progresses to malignancy.

Diagnostic investigation

Laboratory studies

The results of laboratory studies usually are normal in patients with colonic adenomas. Intermittent bleeding from large polyps may produce a positive result on a fecal occult blood test or may lead to iron deficiency anemia. Large secreting villous adenomas may cause electrolyte abnormalities.

Radiographic studies

Research shows that double-contrast barium enema radiography detects only 50% of colonic polyps over 1 cm in size, with a specificity of 85%. Air insufflation enhances mucosal detail and exposes polyps, which appear as intralumenal protrusions coated with barium or as discrete rings with barium collected at their bases or along the stalks of pedunculated polyps. The rectosigmoid region is often difficult to visualize, even by experienced radiologists. Therefore, flexible or rigid sigmoidoscopy is necessary for complete evaluation of the colon. Barium enema radiography does not afford the capability to obtain histological specimens; thus colonoscopy is required when a barium study suggests the presence of a colonic polyp. Computed tomography colonography (CTC) technology has been progressing rapidly, and can now be performed with contrast tagging of stool to allow for digital subtraction of intraluminal contents. CTC has been shown to have a 90% sensitivity for polyps 1 cm in size or larger with a specificity of 86%. However, to optimize performance, experienced radiologists and state-of-the-art software and hardware are needed.

Endoscopic studies

Colonoscopy is the procedure of choice if the clinical presentation suggests that a patient has a colonic polyp. Colonoscopy possesses the highest sensitivity and specificity of any diagnostic modality for detecting adenomatous polyps, and it also allows for biopsy and removal of polyps, thereby fulfilling a therapeutic role. However, colonoscopy is not infallible. Studies of patients undergoing two colonoscopies within a short time demonstrate that 22% of polyps are missed. Although methods to distinguish polyp histology during colonoscopy are being studied, it is not yet possible to reliably distinguish polyp subtypes by endoscopic appearance alone. Therefore, histopathological analysis is the definitive diagnostic test. It also informs assessment of future risk of colorectal cancer.

Histological evaluation

Adenomas are classified by their dominant histology. Tubular adenomas are the most common (85%); tubulovillous adenomas (10%), villous adenomas (5%), and serrated adenomas (hyperplastic intermingled with adenomatous features, 1%) account for the remainder. In general, the risk of high-grade dysplasia or invasive adenocarcinoma correlates with the size of the polyp and the degree of villous architecture.

Management and prevention

Endoscopy and surgery

Most adenomatous polyps can be removed by endoscopic polypectomy using either a snare (with or without electrocautery) or biopsy forceps. Most polyps can be completely removed in a single resection, and the intact polyp can be examined histologically to confirm the absence of adenomatous tissue at the resection margin. Large, broad-based, sessile polyps may require saline injection to lift the polyp, followed by piecemeal snare resection. In general, polypectomy is safe; the major complication rate is less than 2%. If endoscopic removal of large or multiple polyps is not possible, laser ablation, argon plasma coagulation, or surgical resection may be necessary. The safe removal of large, sessile polyps sometimes requires surgery.

Because synchronous polyps are common (50%) in patients with adenomatous polyps, a patient with a documented colonic adenoma should undergo a colonoscopic examination of the entire colon. Similarly, the prevalence of recurrent (metachronous) polyps warrants a surveillance program of follow-up colonoscopies to detect the development of new polyps before they progress to adenocarcinoma. The data from the National Polyp Study suggest that the recurrence rate for metachronous polyps is about 10% per year. Polyps with high-grade atypia and multiple polyps have a higher recurrence rate. Current recommendations advise surveillance colonoscopy every 3 years if three or more adenomas are removed or if any polyp is over 1 cm in size or contains villous histology or high-grade dysplasia. A 5–10-year interval is appropriate if 1–2 small (<1 cm diameter) adenomas are found. More frequent surveillance is advised when there is doubt about the adequacy of the polyp resection or if the patient has multiple (e.g. >10) neoplasms.

Malignant polyps

Colonic adenomas with severe atypia or noninvasive carcinoma do not metastasize because there are no lymphatic channels above the muscularis mucosae. These lesions are cured by colonoscopic polypectomy. When malignant cells penetrate the muscularis mucosae, the polyp is considered an invasive carcinoma. In this case, the decision to perform colonoscopic resection only or surgical resection is based on the characteristics of the malignant polyp. Poor prognostic features include the presence of incomplete endoscopic resection, a poorly differentiated carcinoma, a carcinoma within 2 mm of the polypectomy margin, venous or lymphatic invasion, sessile (not pedunculated) morphology, or extension beyond the base of the polyp stalk. Surgical resection of the underlying bowel is recommended if one or more of these features is present. Pedunculated polyps that can be completely resected and that lack all high-risk features may be treated with polypectomy alone. All patients with malignant polyps who are treated with polypectomy alone should have surveillance colonoscopy within 1–3 months and at 1 year.

Chemoprevention

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) including aspirin have been associated with reduced incidence and mortality from colorectal cancer. Several NSAIDs including sulindac and celecoxib have been shown to effectively decrease the incidence of recurrent adenomas in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. However, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends against the use of aspirin or NSAIDs for the primary prevention of colorectal cancer due to concerns about potential harms.

Familial Adenomatous Polyposis

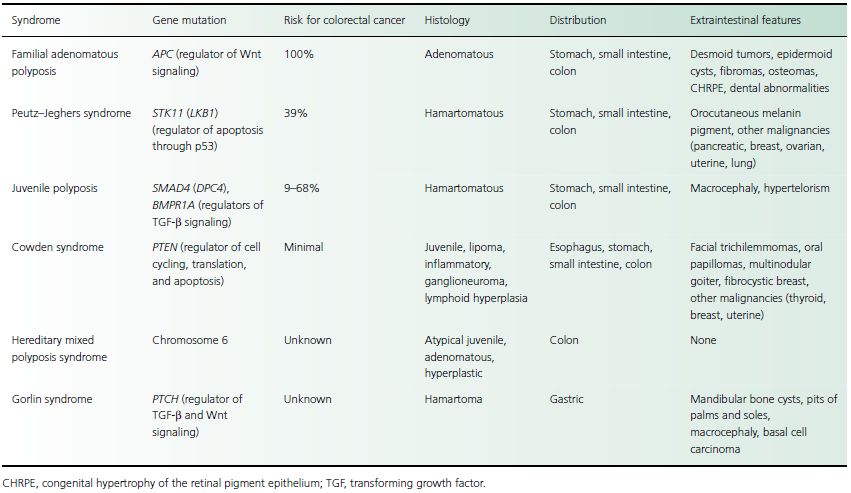

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), also known as adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) or familial polyposis coli, is an autosomal dominant disease characterized by the early onset of hundreds or thousands of intestinal polyps with an inevitable progression to colon cancer. FAP is one of many known polyposis syndromes (Table 30.2). Three adenomatous polyposis syndromes are variants of FAP: Gardner syndrome, attenuated adenomatous polyposis coli (attenuated FAP), and Turcot syndrome.

Clinical presentation

Gastrointestinal polyposis

Patients with FAP usually develop adenomatous polyps in adolescence or young adulthood, but colonic adenomas have been reported as early as age 4 and as late as age 40. Polyps often carpet the colon and number in the hundreds to thousands, but they rarely produce symptoms until late in the course of disease. Patients not previously identified as having FAP may present with rectal bleeding, diarrhea, and abdominal pain in the third and fourth decades, at which time they likely harbor colon cancer. Cancer is diagnosed at the mean age of 39, and more than 90% of patients develop cancer by age 50. Patients with attenuated FAP often have fewer polyps, and the onset of adenomas and progression to adenocarcinoma is delayed by 10 years. Differentiating these patients from patients with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) may be difficult, but the presence of duodenal polyps or extraintestinal features of FAP may be helpful clues.

Table 30.2 Polyposis syndromes

Gastric polyps are present in 23–100% of patients with FAP. If present, they usually are numerous, asymptomatic, located in the proximal fundus or body, and have a hamartomatous (nonneoplastic, fundic gland) histology. Adenomatous polyps of the stomach occur in 10% of patients with FAP, usually in the antrum but occasionally in the body or fundus.

Duodenal polyps occur in 50–90% of patients with FAP, and in contrast to gastric polyps, they usually are adenomatous. These polyps tend to be multiple, developing in the periampullary region, where they may rarely cause biliary obstruction or pancreatitis. The lifetime risk of developing cancer from duodenal adenomas is 3–5%. Cancer develops most commonly in the periampullary region and is one of the most common causes of death in patients with FAP who have undergone prophylactic colectomy. Adenomas may also develop in the jejunum (50%) and ileum (20%), but malignant transformation is rare.

Extraintestinal manifestations

Gardner syndrome is a subtype of FAP with characteristic extraintestinal manifestations. Desmoid tumors are benign mesenchymal neoplasms that occur throughout the body but frequently in the mesentery and other intra-abdominal regions. These masses may infiltrate adjacent structures or compress adjacent visceral organs or blood vessels, producing abdominal pain. Abdominal examination may demonstrate a mass lesion. Osteomas are benign bony growths that occur throughout the skeletal system but most commonly involve the skull and mandible. They have no malignant potential and generally do not cause symptoms. Dental abnormalities include dental cysts, unerupted teeth, supernumerary teeth, and odontomas. These lesions are benign and generally cause no symptoms.

Cutaneous lesions associated with FAP include epidermoid cysts, sebaceous cysts, fibromas, and lipomas. Epidermoid cysts are located on the extremities, face, and scalp. Fibromas most commonly occur on the scalp, shoulders, arms, and back. Infected cysts may cause symptoms.

Congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (CHRPE), or pigmented ocular fundus lesion, affects 60–85% of patients with FAP. This retinal abnormality is characterized by hamartomas of the retinal epithelium, which appear as multiple, discrete, round or oval areas of hyperpigmentation. Although the pathogenesis of CHRPE remains unknown, the presence of multiple lesions in both eyes is essentially pathognomonic for FAP.

Turcot syndrome is characterized by adenomatous polyposis in association with central nervous system malignancies, such as medulloblastomas, astrocytomas, and ependymomas, which usually manifest within the first two decades of life. Neurological surveillance may be indicated for persons at risk of developing FAP, especially in families with Turcot syndrome. Two-thirds of those with Turcot syndrome have APC

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree