Upper endoscopy

Urgent upper endoscopy is indicated for hemorrhage that does not stop spontaneously or in patients with suspected cirrhosis or aortoenteric fistulae. Upper endoscopy is contraindicated when perforation is suspected and is relatively contraindicated in patients with compromised cardiopulmonary status or depressed consciousness. In such cases, endotracheal intubation with mechanical ventilation may enhance the safety of the technique. Upper GI barium radiography is not performed in the acute setting in a potentially unstable patient because it offers no therapeutic capability and may obscure endoscopic or angiographic visualization of the bleeding site.

Scintigraphy and angiography

When hemorrhage is so brisk that it obscures endoscopic visualization, scintigraphic and angiographic studies may be indicated. Scintigraphic 99mTc-sulfur colloid- or 99mTc-pertechnetate-labeled erythrocyte scans can localize bleeding to an area of the abdomen if the rate of blood loss exceeds 0.5 mL/min. They are used to determine if angiography is feasible and to direct the angiographic search and minimize any dye load. Angiography can localize the bleeding site if the rate of blood loss is greater than 0.5 mL/min and can offer therapeutic capability.

Other radiographic studies

If an aortoenteric fistula is suspected, a vigorous diagnostic approach, including abdominal computed tomographic or magnetic resonance imaging studies, should be pursued after endoscopy has excluded other bleeding sources.

Obscure GI bleeding

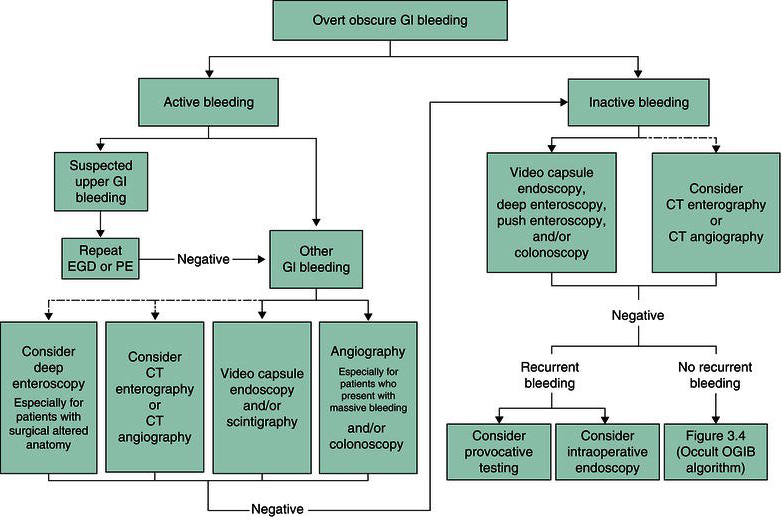

Obscure GI bleeding is defined as bleeding that is either persistent or recurrent and is of unknown origin after an appropriate endoscopic evaluation. Obscure GI bleeding may be overt (i.e. blood is visible, such as with melena or hematochezia) or occult (i.e. no gross blood is evident but there is either iron deficiency anemia or occult blood detectable in the stool). A suggested algorithm for the evaluation of obscure, overt GI bleeding is shown in Figure 3.1.

Differential diagnosis

The most common causes of upper GI hemorrhage are peptic ulcer disease, gastropathy (or gastric erosions), and sequelae of portal hypertension (i.e. esophageal and gastric varices, portal gastropathy). Other disorders comprise a small minority of cases (Table 3.1).

Peptic ulcer disease

Duodenal, gastric, and stomal ulcers cause 50% of upper GI bleeding. Bleeding occurs if an ulcer erodes into the wall of a vessel, which may loop into the floor of the ulcer crater, forming an aneurysmal dilation. Most cases of peptic ulcer disease result from gastric infection with Helicobacter pylori or from chronic use of aspirin or NSAIDs. Stigmata of recent bleeding from ulcer sources on endoscopy that are predictors of poor outcome include active arterial spurting, oozing of blood, a visible vessel (an elevated red, blue, or gray mound that resists washing), and adherent clot. Other prognostic indicators include amount of blood lost, patient age, concomitant disease, onset of bleeding while hospitalized, giant ulcers larger than 2 cm, and need for emergency surgery.

Gastropathy

Gastropathy may be produced by several mechanisms. Endoscopically, gastropathy may be visualized as mucosal hemorrhages, erythema, or erosions. An erosion, in contrast to an ulcer, represents a break in the mucosa of less than 5 mm that does not traverse the muscularis mucosae. In addition to causing ulcers, NSAIDs produce erosions most often in the antrum that usually resolve after removing the offending agent. Ethanol is a gastric mucosal irritant when administered in high concentrations. Stress gastritis develops in patients in the intensive care unit who have underlying respiratory failure, hypotension, sepsis, renal failure, burns, peritonitis, jaundice, or neurological trauma. Although most patients in the intensive care unit have gastric mucosal abnormalities on endoscopy, only 2–10% develop gross hemorrhage. The hallmark of stress gastritis is the presence of multiple bleeding sites, which limit the therapeutic options.

Figure 3.1 Suggested diagnostic approach to overt obscure GI bleeding. Dashed arrows indicate less preferred options. Positive test results should direct specific therapy. Because diagnostic tests can be complementary, more than one test may be needed, and the first-line test may be based upon institutional expertise and availability. CT, computed tomography; EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy; OGIB, obscure GI bleeding; PE, push enteroscopy. (Source: ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, The Role of Endoscopy in the Management of Obscure GI Bleeding, Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 72:475; with permission from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.)

Table 3.1 Causes of gross gastrointestinal hemorrhage

| Upper gastrointestinal sources Peptic ulcer disease (duodenal, gastric, stomal) Gastritis (NSAID, stress, chemotherapyinduced) Varices (esophageal, gastric, duodenal) Portal gastropathy Mallory–Weiss tear Esophagitis and esophageal ulcers (acid reflux, infection, pill induced, sclerotherapy, radiation induced) Neoplasms Vascular ectasias and angiodysplasias Gastric antral vascular ectasia Aortoenteric fistula Hematobilia Hemosuccus pancreaticus Dieulafoy lesion Lower gastrointestinal sources Diverticulosis Angiodysplasia Hemorrhoids Anal fissures Neoplasms Inflammatory bowel disease Ischemic colitis Infectious colitis Radiation-induced colitis Meckel diverticulum Intussusception Aortoenteric fistula Solitary rectal ulcers NSAID-induced cecal ulcers |

Hemorrhage secondary to portal hypertension

Patients with portal hypertension are predisposed to hemorrhage from esophageal and gastric varices and portal hypertensive gastropathy. However, up to 50% of upper GI bleeds in patients with cirrhosis do not result from these causes. Variceal size is the best predictor of esophageal variceal hemorrhage because wall tension is determined by the diameter of a hollow vessel. Other predictors of esophageal variceal bleeding include the red color sign, which is the result of microtelangiectasia; red wale marks, which appear as whip marks; hemocystic spots, which appear as blood blisters; and diffuse redness. The white nipple sign, a platelet-fibrin plug, is diagnostic of previous hemorrhage but does not predict rebleeding.

Gastric varices are present in 20% of patients with portal hypertension and develop in another 8% after esophageal variceal obliteration. Isolated gastric varices suggest splenic vein thrombosis, which may be a consequence of pancreatic disease and is treated by splenectomy. Portal hypertensive gastropathy appears endoscopically as a mosaic, snakeskin-like mucosa as a result of engorged mucosal vessels that may bleed briskly or produce insidious iron deficiency anemia.

Miscellaneous causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding

Mallory–Weiss tears are linear breaks in the mucosa of the gastroesophageal junction that are induced by retching, often in patients who have consumed alcohol. Most Mallory–Weiss tears resolve spontaneously with conservative management. Esophagitis and esophageal ulcers result from acid reflux, radiation therapy, infections with Candida albicans and herpes simplex virus, pill-induced damage, or iatrogenic sources (e.g. sclerotherapy). Hemorrhage from erosive duodenitis is similar to duodenal ulcer bleeding but usually is less severe because the lesions are shallower. Neoplasms most commonly bleed slowly, but occasionally exhibit massive hemorrhage. Vascular ectasias occur less commonly in the stomach and duodenum than in the colon and cause recurrent acute GI hemorrhage that may require frequent blood transfusions. Vascular ectasias often occur as a consequence of advanced age, but also are associated with chronic renal failure, aortic valve disease, and prior radiation therapy.

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, or Osler–Weber–Rendu syndrome, is an autosomal dominant disorder with telangiectasia of the tongue, lips, conjunctiva, skin, and mucosa of the gut, bladder, and nasopharynx. Gastric arteriovenous ectasia (GAVE), or watermelon stomach, has the appearance of columns of vessels along the tops of the antral longitudinal rugae. Biopsies show dilated mucosal capillaries with focal thrombosis and fibromuscular hyperplasia of lamina propria vessels. Aortoenteric fistulae may produce fatal hemorrhage from the third portion of the duodenum in patients who have undergone prior synthetic aortic graft surgery. This patient may present with a minor “herald” hemorrhage before fatal exsanguination occurs.

Hematobilia and hemosuccus pancreaticus present with hemorrhage from the ampulla of Vater and are complications of liver trauma or biopsy, malignancy, hepatic artery aneurysm, hepatic abscess, gallstones, and pancreatic pseudocyst. Bleeding in a Dieulafoy lesion results from pressure erosion of the overlying epithelium by an ectopic artery in the proximal stomach without surrounding ulceration or inflammation. Some patients present with upper GI bleeding from epistaxis, hemoptysis, oral lesions, or factitious blood ingestion.

Management

Resuscitation

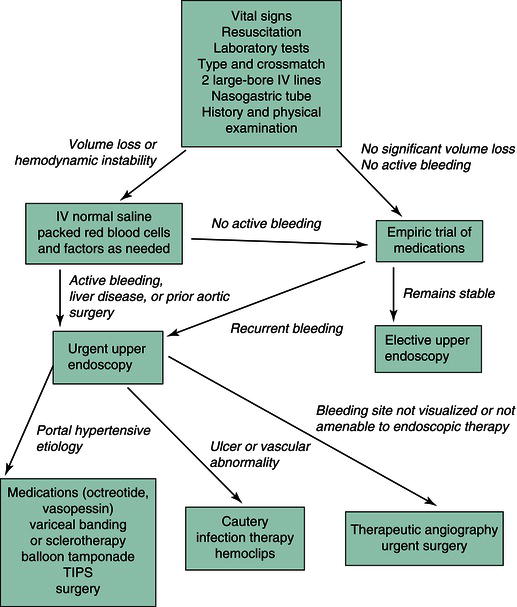

The first step in managing a patient with upper GI bleeding is to assess the urgency of the clinical condition (Figure 3.2). Hematemesis, melena, or hematochezia suggest major hemorrhage, whereas pallor, hypotension, and tachycardia indicate substantial blood volume loss (>40% of total volume) and mandate immediate volume replacement. A patient with GI bleeding and postural or supine hypotension must be admitted to an intensive care unit. Two large-bore intravenous catheters should be inserted. A nasogastric tube should be placed. A bright red aspirate that does not clear with lavage of room temperature water is an indication for urgent endoscopy because it is associated with a 30% mortality, whereas coffee grounds-colored material that clears permits further assessment in a hemodynamically stable patient. A clear aspirate is found in some patients with duodenal bleeding. Thus, the clinician cannot be complacent if unstable hemodynamic parameters indicate ongoing blood loss. In addition to diagnostic laboratory testing, blood samples are sent for blood typing and cross-matching. Intravascular volume should be replenished with normal saline while awaiting the availability of blood products.

Figure 3.2 Work-up of a patient with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. IV, intravenous; TIPS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

Transfusion of blood products

The need for blood transfusion is influenced by patient age, coexistent cardiovascular disease, and persistent hemorrhage. Generally, the hematocrit should be maintained above 30% in elderly patients and above 20% in younger patients with active hemorrhage. Packed erythrocytes are preferred for blood transfusion to avoid fluid load. If coagulation studies are abnormal, as in cirrhosis, fresh-frozen plasma or platelets also may be needed. Patients without coagulopathy may need fresh-frozen plasma and platelet transfusion if multiple transfusions have been given, because transfused blood is deficient in some clotting factors. Warmed blood should be transfused in patients with massive blood loss (>3 L) to prevent hypothermia. Some individuals with massive bleeding also require supplemental calcium to counter the calcium-binding effects of preserved blood.

Medications

Empiric medical treatment is often given before the evaluation is complete. For presumed peptic disease, intravenous proton pump inhibitor therapy may be given as studies have demonstrated reduced rates of rebleeding from ulcers and it may downstage the severity of the bleeding source. Proton pump inhibitors also play prominent roles in prophylaxis against development of erosions in patients on NSAIDs. Patients with H. pylori infection should be given combined therapy including antibiotics to eradicate the organism, even those who may have mucosal injury secondary to NSAIDs. Prophylaxis against stress gastropathy should be provided for patients at risk in intensive care units. For presumed varices or portal gastropathy, intravenous octreotide is begun when bleeding is diagnosed. Antibiotics (e.g. quinolones or ceftriaxone) should be administered to cirrhotics with acute GI bleeding, irrespective of the presence or absence of varices or the cause of bleeding, as they have been proven to reduce morbidity and mortality in this setting.

Therapeutic endoscopy

Before endoscopy, it may be beneficial to lavage the stomach through a large-bore orogastric tube with room temperature saline or water to enhance mucosal visualization. Alternatively, intravenous erythromycin can be administered to help clear the stomach of retained blood. Bleeding esophageal varices may be managed by endoscopic placement of rubber bands to constrict the bleeding site or by direct injection of a sclerosant solution such as sodium morrhuate. These therapies have initial success rates of 85–95% for controlling active hemorrhage. Band ligation may exhibit lower complication rates compared to sclerotherapy. Multiple courses of banding or sclerotherapy can be recommended to reduce rates of rebleeding. The role of endoscopy in managing gastric varices is less well established, although sclerotherapy, thrombin injection, cyanoacrylate injection, and snare ligation have been reported to be effective in small studies.

For nonvariceal hemorrhage, local injection, placement of hemoclips, or cautery may provide effective initial hemostasis and reduce the risk of rebleeding. Meta-analyses suggest reductions in mortality with endoscopic therapy. Solutions that stop bleeding from nonvariceal disease when injected include sclerosants (ethanolamine), vasoconstrictors (epinephrine), and normal saline. Thermal methods of cautery include bipolar electrocautery, heater probe application, argon plasma coagulation, and Nd:YAG laser therapy. Endoscopic visualization of a nonbleeding visible vessel or an adherent clot increases the risk of rebleeding in the patient with ulcer hemorrhage. Thus, for major hemorrhage secondary to ulcer disease, endoscopic therapy should be performed for active bleeding sites as well as visible vessels and adherent clots, which, when washed off, reveal visible vessels or active bleeding. Other sources amenable to cautery include refractory Mallory–Weiss tears, neoplasms, angiodysplasia, or Dieulafoy lesions. Patients with stress gastritis, gastropathy resulting from analgesics, and portal gastropathy usually present with multiple bleeding sites that cannot be controlled endoscopically. Fortunately, bleeding stops spontaneously in many of these individuals.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree