Diarrhea: six or more bowel movements per day, with blood

Fever: mean evening temperature >37.5°C or >37.5°C on at least 2 of 4 days at any time of day

Tachycardia: mean pulse rate higher than 90 beats/min

Anemia: hemoglobin of <7.5 g/dL, allowing for recent transfusions

Sedimentation rate: >30 mm/h

Mild

Mild diarrhea: fewer than four bowel movements per day, with only small amounts of blood

No fever

No tachycardia

Mild anemia

Sedimentation rate: <30 mm/h

Moderately severe

Intermediate between mild and severe

Severe ulcerative colitis can cause life-threatening complications. If the inflammatory process extends beyond the submucosa into the muscularis, the colon dilates, producing toxic megacolon. Clinical criteria suggestive of toxic megacolon include a temperature higher than 38.6°C, a heart rate higher than 120 beats per minute, a neutrophil count of more than 10,500 cells/μL, dehydration, mental status changes, electrolyte disturbances, hypotension, abdominal distension, tenderness (with or without rebound), and hypoactive or absent bowel sounds. Toxic megacolon usually occurs in patients with pancolitis, often early in the course of their disease. Medications that impair colonic motor function may initiate or exacerbate megacolon. Perforation of the colon may complicate toxic megacolon or may occur in cases of severe ulcerative colitis without megacolon. Strictures are uncommon but lumenal narrowing is observed in 12% of patients after 5–25 years of disease, usually in the sigmoid colon and rectum. Strictures present as increases in diarrhea or new fecal incontinence and may mimic malignancy on endoscopic or radiographic evaluation.

Crohn’s disease

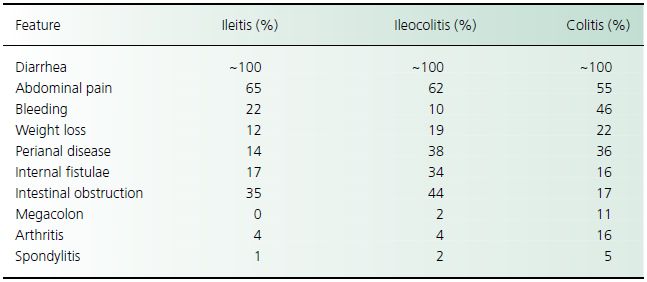

There are three main patterns of disease distribution in Crohn’s disease: (1) involvement of the small and large intestine (40% of patients); (2) disease confined to the small intestine (30%); and (3) disease of only the colon (25%), which is pancolonic in two-thirds and segmental in one-third. Less commonly, the disease affects the proximal gastrointestinal tract (5%). Predominant symptoms in Crohn’s disease include diarrhea, abdominal pain, and weight loss. They may exist for months to years before a diagnosis is made (Table 29.2). With colonic disease, diarrhea may be of small volume with urgency and tenesmus whereas, if disease is extensive, small intestinal involvement produces larger stool volumes with steatorrhea. Diarrhea from small intestinal disease occurs from loss of mucosal absorptive surface area (producing bile salt-induced or osmotic diarrhea), bacterial overgrowth from strictures, and enteroenteric or enterocolonic fistulae. Pain results from intermittent partial obstruction or serosal inflammation. Commonly, pain and distension from terminal ileal disease are reported in the right lower quadrant. Weight loss occurs in most patients because of malabsorption and reduced oral intake; 10–20% of patients lose more than 20% of their body weight. Gastroduodenal involvement in Crohn’s disease produces epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting secondary to stricture or obstruction. Fatigue, malaise, fever, and chills are constitutional symptoms that contribute to the morbidity of Crohn’s disease. The Crohn’s Disease Activity Index assigns numerical scores to stool frequency, abdominal pain, sense of well-being, systemic manifestations, the use of antidiarrheal agents, abdominal mass, hematocrit, and body weight, and has been used as a quantitative measure of disease activity in clinical studies.

Table 29.2 Frequency of clinical features in Crohn’s disease

Crohn’s disease often is associated with gastrointestinal complications. Abscesses and fistulae result from extension of a mucosal breach through the intestinal wall into the extraintestinal tissue. Abscesses occur in 15–20% of patients and most commonly arise from the terminal ileum but they may occur in iliopsoas, retroperitoneal, hepatic, and splenic regions, and at anastomotic sites. Abscesses present with fever, localized tenderness, and a palpable mass. Infection usually is polymicrobial (e.g. Escherichia coli, Bacteroides fragilis, Enterococcus, and α-hemolytic Streptococcus species). Twenty percent to 40% of patients with Crohn’s disease have fistulous disease. Fistulae may be enteroenteric, enterocutaneous, enterovesical, or enterovaginal or perianal. They develop when disease is active and may persist after remission. Large enteroenteric fistulae produce diarrhea, malabsorption, and weight loss. Enterocutaneous fistulae produce persistent drainage that usually is refractory to medical therapy. Rectovaginal fistulae lead to foul-smelling vaginal discharge, and enterovesical fistulae produce pneumaturia and recurrent urinary infection. Obstruction, especially of the small intestine, is a common complication caused by mucosal thickening, muscular hyperplasia and scarring from prior inflammation, or adhesions. Perianal disease, including anal ulcers, abscesses, and fistulae, can also affect the groin, vulva, or scrotum and is a complication that often is difficult to treat. Fistulae drain serous or mucous material, whereas perianal abscesses cause fever, redness, induration, and pain that is exacerbated by defecation, sitting, and walking.

Extraintestinal features

Extraintestinal manifestations of IBD are divided into two groups: those in which clinical activity follows activity of bowel disease and those in which clinical activity is unrelated to bowel activity. Extraintestinal disease is more common with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s colitis than with ileal Crohn’s disease. Colitic arthritis is a migratory arthritis of the knees, hips, ankles, wrists, and elbows that usually lasts a few weeks, rarely produces joint deformity, and usually responds to treatment of bowel inflammation. In contrast, the activities of sacroiliitis and ankylosing spondylitis do not follow the course of the bowel disease and may not respond to therapy for intestinal inflammation. Sacroiliitis often is asymptomatic and is found incidentally by radiography. The prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis, which is characterized by morning stiffness, low back pain, and stooped posture, increases 30-fold with ulcerative colitis and is associated with the HLA-B27 phenotype. Unlike colitic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis can be relentlessly progressive and unresponsive to medications.

Hepatobiliary manifestations of IBD include steatosis, pericholangitis, chronic active hepatitis, cirrhosis, sclerosing cholangitis, and gallstones. Sclerosing cholangitis is a chronic cholestatic disease marked by fibrosing inflammation of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts; it occurs in 1–4% of patients with ulcerative colitis and in lesser numbers of patients with Crohn’s disease. Conversely, the prevalence of IBD is so high in patients with sclerosing cholangitis that colonoscopy should be performed even on those without intestinal symptoms. Cholangiocarcinoma develops in 10–15% of patients with IBD who have long-standing sclerosing cholangitis. Cholesterol gallstones develop in patients with Crohn’s disease because of the bile salt depletion that occurs with ileal disease or resection.

Diagnostic investigation

Laboratory studies

Laboratory studies that reflect disease activity in ulcerative colitis are hemoglobin level, leukocyte count, electrolytes, serum albumin, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein. Neutrophil-derived fecal markers, including calprotectin and lactoferrin, represent a novel tool for monitoring intestinal mucosal inflammation. Anemia, hypoalbuminemia, hypokalemia, and metabolic alkalosis may be prominent in severe disease. Stool should be inspected for leukocytes and cultures should be obtained to rule out infectious etiologies of diarrhea, including Campylobacter, Shigella, Salmonella, Yersinia, and Giardia lamblia. Even if antibiotics have not been taken recently, stool should be tested for Clostridium difficile toxin.

Laboratory findings in Crohn’s disease are nonspecific. Anemia results from chronic disease, blood loss, and iron, folate, and vitamin B12 deficiency, and bone marrow suppression from medication. Active Crohn’s disease elevates leukocyte counts and sedimentation rate but marked increases suggest abscess formation. Hypoalbuminemia may indicate severe disease, malnutrition, or protein-losing enteropathy. For patients with diarrhea, testing of stools for infection is indicated as for ulcerative colitis. Measurement of fecal fat, either qualitatively (Sudan stain) or quantitatively, can provide evidence of ileal disease.

Complications and extraintestinal manifestations of IBD can be suggested by selected laboratory studies. Profound leukocytosis with a neutrophil predominance in ulcerative colitis is worrisome for perforation or toxic megacolon or C. difficile infection. Pericholangitis and sclerosing cholangitis produce elevations of alkaline phosphatase. Pyuria in a patient with Crohn’s disease suggests a possible enterovesical fistula, whereas hematuria raises concern for renal stones.

Endoscopy

Colonoscopy at the initial presentation of a patient with suspected IBD can establish the diagnosis and define the extent of disease. With severe disease, sigmoidoscopy may provide enough information to initiate therapy without the risks of perforation associated with colonoscopy in this setting.

In ulcerative colitis, the inflammation begins in the rectum and extends proximally to the point where visible disease ends without skipping any areas (Table 29.3). Mild disease is characterized by superficial erosions, loss of vascularity, granularity, and exudation. In severe disease, large ulcers and denuded mucosa may dominate. With chronic disease, the mucosa flattens and inflammatory polyps (pseudopolyps) develop. Pseudopolyps are not premalignant and do not need to be resected.

Table 29.3 Colonoscopic findings in inflammatory bowel disease

| Feature | Ulcerative colitis | Crohn’s disease |

| Inflammation | ||

| Distribution | ||

| Colon | ||

| Contiguous | + + + | + |

| Symmetrical | + + + | + |

| Rectum | + + + | + |

| Friability | + + + | + |

| Topography | ||

| Granularity | + + + | + |

| Cobblestoned | + | + + + |

| Ulceration | ||

| Location | ||

| Colitis | + + + | + |

| Ileum | 0 | + + + + |

| Discrete lesion | + | + + + |

| Features | ||

| Size >1 cm | + | + + + |

| Deep | + | + + |

| Linear | + | + + + |

| Aphthoid | 0 | + + + + |

| Bridging | ||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree