Adenoma

Hamartomas (Peutz–Jeghers syndrome, Cronkite–Canada syndrome, juvenile polyposis, Cowden disease, Bannayan–Riley–Ruvalcaba syndrome)

Malignant epithelial tumors

Primary adenocarcinoma

Metastatic carcinoma

Carcinoid tumors

Lymphoproliferative disorders

B-cell

Diffuse large cell lymphoma

Small, noncleaved cell lymphoma

Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma

Mantle cell lymphoma (multiple lymphomatous polyposis)

Immunoproliferative small intestinal disease (IPSID)

T-cell

Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma

Mesenchymal tumors

Gastrointestinal stromal cell tumors (GISTs)

Fatty tumors (lipoma, liposarcoma)

Neural tumors (schwannomas, neurofibromas, ganglioneuromas)

Paragangliomas

Smooth muscle tumors (leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma)

Vascular tumors (hemangioma, angiosarcoma, lymphangioma, Kaposi sarcoma)

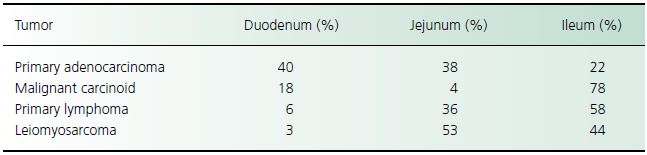

Table 26.2 Distribution of malignant tumors of the small intestine

Management and course

Surgical resection is the treatment of choice for adenocarcinoma of the small intestine. Tumors in the jejunum and proximal ileum are treated with segmental resection. A right hemicolectomy is required to treat adenocarcinoma of the distal ileum. Lesions that involve the ampulla of Vater require pancreaticoduodenectomy (i.e. the Whipple procedure). The long-term survival for primary small bowel adenocarcinoma is 47.6% (local disease), 33% (regional disease), and 3.9% (distal disease). Neither chemotherapy nor radiation therapy is effective for small bowel adenocarcinoma.

Carcinoids

Clinical presentation

The most common clinical presentation of a symptomatic carcinoid tumor of the small intestine is intermittent abdominal pain. Additional complications include intestinal ischemia, intussusception, and gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

The carcinoid syndrome affects 10–18% of patients with small bowel carcinoids. Although localized foregut carcinoids may produce the carcinoid syndrome, carcinoids of the small intestine cause this syndrome only after hepatic metastasis. The characteristic symptoms of the carcinoid syndrome are flushing of the face and neck and intermittent watery diarrhea. Less common symptoms include bronchospasm and right-sided heart failure. Patients with carcinoid syndrome may experience a hypotensive crisis during the induction of general anesthesia.

Diagnostic investigation

Laboratory testing

Measuring the urinary excretion of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), the major metabolite of serotonin, is a sensitive and specific test for the carcinoid syndrome, but it is less accurate for detecting localized carcinoids. Excretion of more than 30 mg of 5-HIAA in a 24-h urine sample after provocative testing is diagnostic of the carcinoid syndrome. False-positive tests may be caused by celiac disease, Whipple disease, tropical sprue, and ingesting food rich in serotonin (e.g. walnuts, bananas, and avocados). Elevation of chromogranin A can also be used for diagnosing carcinoid tumors, as well as for monitoring treatment response or recurrence. The measurement of neuron-specific enolase levels has also been used, but it is a less accurate diagnostic test for carcinoid tumors than the measurement of chromogranin A.

Imaging studies

Because most carcinoids occur in the ileum, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and colonoscopy have limited roles in identifying these tumors. Most symptomatic lesions are visible in barium radiographs of the small intestine. The desmoplastic distortion of the mesentery may be evident as kinking and tethering of the intestine. A CT scan is also helpful in demonstrating these mesenteric changes; it is the procedure of choice for documenting hepatic metastases. Scintigraphy with iodine-123 (123I) or 131I-labeled metaiodobenzylguanidine (I-MIBG), indium-labeled pentetreotide, or octreotide may identify primary and metastatic carcinoids not detected by conventional imaging techniques. Positron emission tomography (PET) can also be used to identify metastatic carcinoids.

Management and course

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree