Coronary artery disease

Coronary artery spasm

Microvascular angina

Mitral valve prolapse

Aortic valve disease

Pericarditis

Dissecting thoracic aortic aneurysm

Mediastinitis

Pneumonia

Pulmonary embolus

Musculoskeletal causes

Costochondritis

Fibromyalgia

Arthritis

Nerve entrapment or compression

Esophageal disease

Gastroesophageal reflux

Achalasia

Diffuse esophageal spasm

Other spastic motor disorders

Infectious or pill-induced esophagitis

Food impaction

Neuropsychiatric causes

Panic disorder

Anxiety disorder

Depression

Somatization

Miscellaneous

Varicella zoster virus reactivation

Additional testing

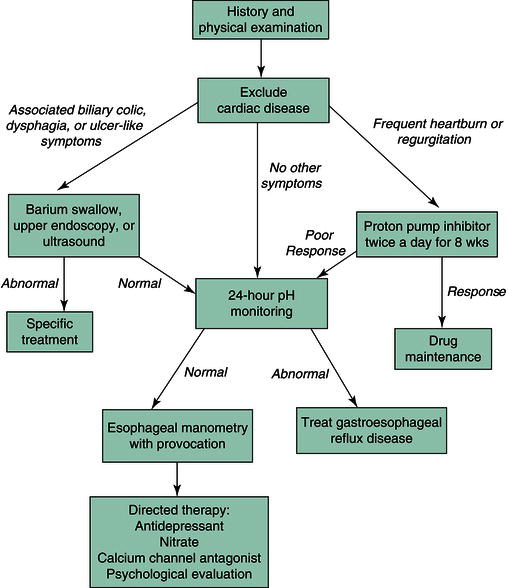

The evaluation of a patient with chest pain is outlined in Figure 2.1. Initial diagnostic tests involve exclusion of cardiac disease. Most patients should undergo electrocardiography, exercise stress testing, echocardiography, or coronary arteriography, depending on their age and risk factors, because the presence of coronary artery disease cannot be established reliably from the history. An ergonovine test may be used to elicit coronary spasm in some patients. Once cardiac disease is excluded, noncardiac sources for chest pain may be evaluated. Musculoskeletal causes usually are detected on physical examination, whereas psychogenic causes may require referral to a mental health specialist for assessment.

Barium swallow radiography or upper endoscopy is used to exclude esophageal mucosal sources of chest pain. Radiographic techniques may observe subtle strictures or dysmotilities, whereas endoscopy is superior for detecting esophagitis and affords the capability to perform a biopsy of suspicious mucosa. When structural studies are normal, gastroesophageal reflux disease should be excluded because of its prevalence as a cause of chest pain. The best test for correlating symptoms with acid reflux is ambulatory pH monitoring of the esophagus using a probe positioned 5 cm above the lower esophageal sphincter. With this procedure, episodes may relate temporally to periods in which esophageal pH decreases. An esophageal pH less than 4 for longer than 5% of total exposure time suggests a diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease with a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 95%. The addition of impedance testing allows for the detection of non-acid reflux events. An empirical trial of high-dose proton pump inhibitor therapy is an alternative to this test and can be expected to relieve symptoms in 80% of patients with noncardiac chest pain and underlying acid reflux.

Esophageal manometry may define an underlying esophageal dysmotility syndrome. By itself, manometry detects potentially pathogenic motor abnormalities in only a minority of patients with noncardiac chest pain. The diagnostic accuracy of manometry may be enhanced by pharmacological challenge with the α-adrenergic stimulant erogonovine, the cholinergic agonist bethanechol, or the cholinesterase inhibitor edrophonium. However, these agents provoke significant side-effects, especially in those individuals with underlying cardiac disease. Furthermore, their clinical utility is unproved. Thus, provocative testing is falling out of favor at many institutions. In some patients, balloon distension of the esophagus reproduces the presenting complaint, which suggests a visceral afferent disturbance as a cause of symptoms. Some centers use this test in their diagnostic evaluations.

Differential diagnosis

Cardiac disease

Cardiac etiologies must be considered in a patient with unexplained chest pain, even in the absence of coronary atherosclerosis. Coronary artery spasm in response to ergonovine is reported in some individuals with chest pain. Exertional chest pain may be a consequence of abnormalities of the smaller endocardial vasculature without evidence of fixed lesions or spasm of the epicardial vessels, a condition termed microvascular angina or syndrome X

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree