Overall Bottom Line

- Ascites is the excessive accumulation of fluid in the peritoneal cavity.

- Eighty percent of cases are due to liver cirrhosis.

- Portal hypertension, reduced effective arterial blood volume, combined with impairment of renal Na+ and water excretion are the main pathogenic mechanisms in cirrhotic ascites.

- Abdominal US is the imaging method of choice in demonstrating ascites.

- Diagnostic paracentesis with cell count and differential, determination of total protein concentration, serum-ascites albumin gradient and ascitic cultures are the essential initial procedures in the diagnostic investigations of a patient with ascites.

- In approximately 90% of patients ascites can be managed with diet and diuretics.

- The formation of grade 2 or 3 ascites is associated with a mortality of 50% and 80% within 2 and 5 years respectively after the first ascites episode.

Section 1: Background

Definition of disease

- Ascites denotes the pathologic accumulation of fluid in the peritoneal cavity.

Disease classification

- According to the amount of ascitic fluid grade 1–3 ascites may be distinguished:

- Grade 1 ascites: mild ascites only detectable by US examination.

- Grade 2 ascites: moderate ascites, manifest on physical examination by moderate symmetrical distension of the abdomen.

- Grade 3 ascites: large, tense ascites or gross ascites with marked abdominal distension.

- Grade 1 ascites: mild ascites only detectable by US examination.

- May be classified depending on whether or not ascites can be managed successfully with dietary salt restriction and diuretics alone

- Uncomplicated ascites is differentiated from refractory (complicated) ascites (see Section 3).

Incidence/prevalence

- Approximately 25% of patients with compensated cirrhosis develop ascites during a follow up period of 10 years.

Etiology

Causes of ascites

| Cause | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Parenchymal liver disease: Cirrhosis Fulminant liver failure | 78 77 1 |

| Malignancy: Peritoneal carcinomatosis (gynecological tumors, gastric carcinoma, extensive liver metastases) | 12 |

| Cardiovascular disease: Congestive heart failure Constrictive or restrictive cardiomyopathy Thrombosis of inferior vena cava Budd–Chiari syndrome Veno-occlusive disease | 5 |

| Infection: Tuberculosis Fitz–Hugh–Curtis syndrome (chlamydiae, gonococci) Coccidioidomycosis Whipple’s disease (Tropheryma whipplei) | 2 |

| Renal: Nephrotic syndrome Uremia Hemodialysis | 1.5 |

| Pancreatic | 1 |

| Bacterial peritonitis | 0.5 |

| Other rare causes: Marked hypothyroidism Collagen vascular disease Familial Mediterranean fever Amyloidosis Hereditary angioneurotic edema Menetrier’s disease and protein-losing enteropathy Starch peritonitis Trauma Arterioportal fistula after liver biopsy Pregnancy specific liver diseases Ovary overstimulation syndrome |

Causes of chylous ascites*

| Neoplastic (e.g. lymphoma, carcinoid tumors, Kaposi’s sarcoma) |

| Cirrhotic (common in adults) |

| Infectious: Tuberculosis Atypical mycobacteriosis (Mycobacterium avium intracellulare) Filariasis (Wuchereria bancrofti) Whipple’s disease (Tropheryma whipplei) |

| Inflammatory: Radiation Pancreatitis Constrictive pericarditis Retroperitoneal fibrosis Sarcoidosis Celiac sprue Retractile mesenteritis |

| Post-operative: Abdominal aneurysm repair Retroperitoneal node dissection Catheter placement for peritoneal dialysis Inferior vena cava resection |

| Traumatic: Blunt abdominal trauma Battered child syndrome |

| Congenital: Primary lymphatic hypoplasia Yellow nail syndrome Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome Primary lymphatic hyperplasia Intestinal lymphangiectasia (“megalymphatics”) |

| Other causes: Right heart failure Dilated cardiomyopathy Nephrotic syndrome Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (10% of cases show chylous ascites) |

* Chylous ascites is a milky-appearing peritoneal fluid (lymph) that is rich in triglycerides (often greater than 1000 mg/dL).

Pathogenesis

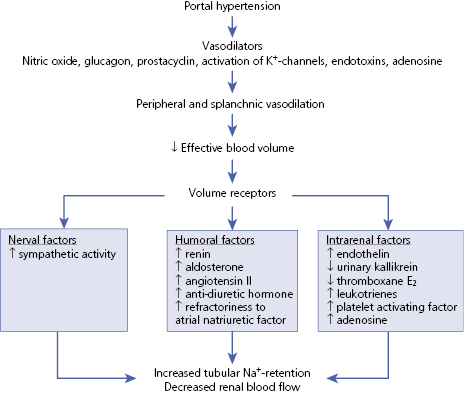

- Portal hypertension is the main underlying pathogenetic factor in the development of ascites in patients with liver cirrhosis.

- Various mediators in portal hypertensive patients lead to peripheral and splanchnic vasodilation with reduction of the effective arterial blood volume, combined with an impairment of renal Na+ and water excretion.

- In liver cirrhosis the balance between the extracellular fluid and Na+-excretion is disrupted, i.e. despite an elevated extracellular fluid volume, Na+ is inadequately retained (Algorithm 19.1).

– – – – – – – – – –

Algorithm 19.1 Pathogenetic factors responsible for increased Na+-retention in liver cirrhosis

– – – – – – – – – –

Section 2: Prevention

- The key to prevention of ascites is prevention and treatment of the underlying disease(s).

Screening

- US is the most cost-effective imaging modality for the diagnosis of ascites. It detects as little as 100 mL ascites.

- CT and MRI are not superior to US in the diagnosis of ascites.

- There is no evidence that screening for ascites improves the outcome of patients with liver cirrhosis.

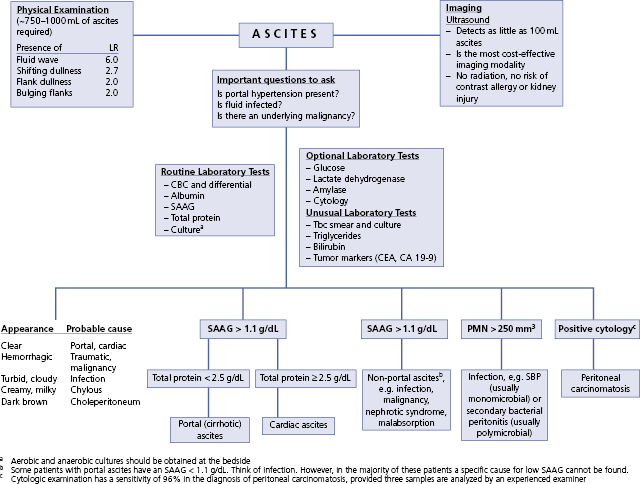

Section 3: Diagnosis (Algorithm 19.2)

– – – – – – – – – –

Algorithm 19.2 Diagnostic approach to ascites

– – – – – – – – – –

Clinical Pearls

- A detailed history will provide the first clues to the presence and possible etiology of liver disease. Look for evidence of past hepatitis B (± D) or C, alcohol abuse, metabolic syndrome, autoimmune hepatitis.

- Physical examination is unreliable in diagnosing small amounts of ascites. The most informative examination finding is shifting dullness to percussion. However, eliciting this sign requires at least 750–1000 mL of ascites.

- Abdominal sonography is the imaging method of choice in demonstrating as little as 100 mL of ascites.

- US-guided paracentesis allows for obtaining ascitic fluid for further laboratory examinations, such as cell count and differential, SAAG, bacterial culture and cytology.

Differential diagnosis

- The differential diagnosis of ascites must include all the causes listed in the tables Causes of ascites/chylous ascites. Liver cirrhosis, malignancy and cardiovascular diseases account for 95% of all cases of ascites in Western countries.

- Four initial questions have to be answered when dealing with a patient with ascites:

- What is the underlying cause? The diseases listed in the tables Causes of ascites/chylous ascites and the various etiologies of liver cirrhosis must be considered.

- What is the SAAG and the total ascitic protein content?

- Is ascites malignant?

- Is ascites infected?

- What is the underlying cause? The diseases listed in the tables Causes of ascites/chylous ascites and the various etiologies of liver cirrhosis must be considered.

Causes of ascites based on the macroscopic appearance of ascitic fluid

| Macroscopic appearance | Possible cause |

|---|---|

| Serous | Portal hypertensive Infectious Malignant Pancreatic |

| Hemorrhagic | Malignant Pancreatic Traumatic |

| Cloudy | Infectious (bacterial) Malignant Pancreatic |

| Chylous | Malignant Portal hypertensive |

Causes of ascites based on serum-ascites albumin gradient

| High gradient (≥1.1 g/dL) | Low gradient (<1.1 g/dL) |

|---|---|

| Cirrhosis Alcoholic hepatitis Cardiac failure Massive liver metastases Fulminant hepatic failure Budd–Chiari syndrome Veno-occlusive disease Portal vein thrombosis Fatty liver of pregnancy Myxedema | Peritoneal carcinomatosis Tuberculous peritonitis Pancreatic ascites Biliary ascites Nephrotic syndrome Serositis Bowel infarction |

Typical presentation

- Cirrhotic ascites usually develops gradually, unnoticed by the patient and the physician. Often the patient complains of increasing meteorism before ascites becomes clinically manifest (“first the wind, and then the rain”).

- Increasing abdominal girth and ankle edema are clinical evidence for the development of ascites in a cirrhotic patient.

Clinical diagnosis

History

- Enquire about past liver disease, potential risk factors associated with liver disease, such as intravenous drug use, promiscuity, previous viral infections, metabolic factors, e.g. obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

- History of prior malignant disease.

Physical examination

- General appearance of the patient:

- Facies alcoholica, alcoholic smell, fetor hepaticus (sweetish, ammoniacal, musty breath in patients with severe parenchymal liver disease).

- Is the patient lethargic, confused?

- Distended abdomen, umbilical hernia, penile or scrotal edema, generalized edema.

- Cutaneous signs of chronic liver disease.

- Gynecomastia.

- Facies alcoholica, alcoholic smell, fetor hepaticus (sweetish, ammoniacal, musty breath in patients with severe parenchymal liver disease).

- Physical examination is unreliable in diagnosing small amounts of ascites. The characteristic signs of ascites are bulging flanks in the supine position, tympany at the top of the abdominal wall (gas-filled small intestinal loops float on top of the fluid), shifting dullness when the patient turns to one side, and a fluid wave that may be elicited by tapping the patient’s flank with a hand.

- The sensitivity and specificity of physical examination for the determination of ascites (equal clinical skills provided) depend primarily on the amount of peritoneal fluid present. The demonstration of shifting dullness is highly sensitive (up to 86%), while clear evidence of a fluid wave is highly specific (up to 82%) for the presence of ascites. However, eliciting these signs usually requires a minimum of approximately 750–1000 mL of ascites. If shifting dullness is absent, 750–1000 mL of ascites can be excluded with an accuracy of >90%.

- Spider nevi, splenomegaly, dilated and prominent abdominal wall veins suggest cirrhosis.

- Congested neck veins, systolic pulsations of jugular veins or of the liver may be observed in congestive right heart failure.

- Pulsus paradoxus and a positive Kussmaul sign suggest constrictive pericarditis.

- A pulsatile liver has been described in tricuspid regurgitation with pulmonary hypertension, and in constrictive pericarditis.

- Visible veins on the patient’s back suggest obstruction of the inferior vena cava.

- Palpable abdominal masses, an immobile mass at the umbilicus (Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule) or a coarse and nodular liver surface are highly suggestive of peritoneal carcinomatosis and metastatic liver disease.

- Spider nevi, splenomegaly, dilated and prominent abdominal wall veins suggest cirrhosis.

Disease severity classification

See also Section 1.

Uncomplicated versus complicated ascites

| Uncomplicated ascites | Complicated ascites* | |

|---|---|---|

| Ascites grade† | Grade 1 or 2 | Grade 3 |

| Encephalopathy | − | + |

| Na+ in 24 hours urine | >20 mmol | <10 mmol |

| Serum Na+ | >130 mmol/L | <130 mmol/L |

| Serum K+ | 3.6–4.9 mmol/L | <3.5 or >5 mmol/L |

| Serum creatinine | <1.5 mg/dL | >1.5 mg/dL |

| Serum albumin | >3.5 g/dL | <3.5 g/dL |

* Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis may be present.

† See Section 1.

Refractory ascites

- Ascites refractory to therapy – either diuretic-resistant or diuretic-intractable ascites – occurs in 5–10 % of patients with cirrhotic ascites.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree