“Mixed” (portal hypertension plus another cause, e.g. cirrhosis and peritoneal carcinomatosis)

Heart failure

Malignancy

Tuberculosis

Fulminant hepatic failure

Pancreatic

Nephrogenous (“dialysis ascites”)

Miscellaneous*

*Includes biliary ascites and chylous ascites resulting from lymphatic tears, lymphoma, and cirrhosis.

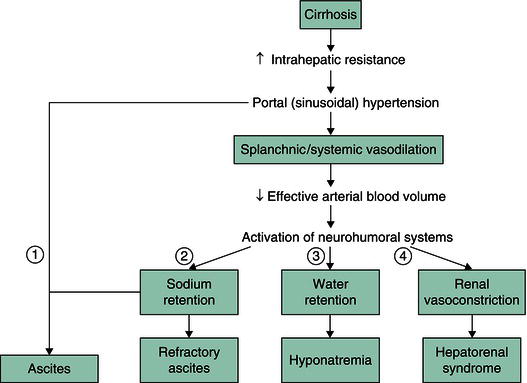

Figure 14.1 Common pathogenesis of ascites, hyponatremia and hepatorenal syndrome. Ascites (1) results from increased sinusoidal pressure and sodium retention. Sinusoidal pressure increases as a result of increased intrahepatic resistance. Sodium retention results from splanchnic and systemic vasodilation that leads to decreased effective arterial blood volume and subsequent upregulation of sodium-retaining hormones. With progression of cirrhosis and portal hypertension, vasodilation is more pronounced, leading to further activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone and sympathetic nervous systems. The resulting increase in sodium and water retention can lead to refractory ascites (2) and hyponatremia (3), respectively, while the resulting increase in vasoconstrictors can lead to renal vasoconstriction and hepatorenal syndrome (4). (Source: Yamada T et al. (eds) Principles of Clinical Gastroenterology. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2008.)

Cardiac disease

Ascites is an uncommon complication of both high-output and low-output heart failure. High-output failure is associated with decreased peripheral resistance; low-output disease is defined by reduced cardiac output. Both lead to decreased effective arterial blood volume and, subsequently, to renal sodium retention. Pericardial disease is a rare cardiac cause of ascites.

Renal disease

Nephrotic syndrome is a rare cause of ascites in adults. It results from protein loss in the urine, leading to decreased intravascular volume and increased renal sodium retention. Nephrogenous ascites is a poorly understood condition that develops with hemodialysis; its optimal treatment is undefined and its prognosis is poor. Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis is an iatrogenic form of ascites that takes advantage of the rich vascularity of the parietal peritoneum to eliminate endogenous toxins and control fluid balance. Urine may accumulate in the peritoneum in newborns or as a result of trauma or renal transplantation in adults.

Pancreatic disease

Pancreatic ascites develops as a complication of severe acute pancreatitis, pancreatic duct rupture in acute or chronic pancreatitis, or leakage from a pancreatic pseudocyst. Many patients with pancreatic ascites have underlying cirrhosis. Pancreatic ascites may be complicated by infection or left-sided pleural effusion.

Biliary disease

Most cases of biliary ascites result from gallbladder rupture, which usually is a complication of gangrene of the gallbladder in elderly men. Bile also can accumulate in the peritoneal cavity after biliary surgery or biliary or intestinal perforation.

Malignancy

Malignancy-related ascites signifies advanced disease in most cases and has a dismal prognosis. Exceptions are ovarian carcinoma and lymphoma, which may respond to debulking surgery and chemotherapy, respectively. The mechanism of ascites formation depends on the location of the tumor. Peritoneal carcinomatosis produces exudation of proteinaceous fluid into the peritoneal cavity, whereas primary hepatic malignancy or liver metastases are likely to induce ascites by producing portal hypertension, either from vascular occlusion by the tumor or arteriovenous fistulae within the tumor. Chylous ascites can result from lymph node involvement with tumor.

Infectious disease

In the United States, tuberculous peritonitis is a disease of Asian, Mexican, and Central American immigrants, and it is a complication of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). One half of patients with tuberculous peritonitis have underlying cirrhosis, usually secondary to ethanol abuse. Patients with liver disease tolerate antituberculous drug toxicity less well than patients with normal hepatic function. Exudation of proteinaceous fluid from the tubercles lining the peritoneum induces ascites formation. Coccidioides organisms cause infectious ascites formation by a similar mechanism. For sexually active women who have a fever and inflammatory ascites, chlamydia-induced, and the less common gonococcus-induced, Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome should be considered.

Chylous ascites

Chylous ascites is a result of the obstruction of or damage to chyle-containing lymphatic channels. The most common causes are lymphatic malignancies (e.g. lymphomas, other malignancies), surgical tears, and infectious causes.

Other causes of ascites formation

Serositis with ascites formation may complicate systemic lupus erythematosus. Meigs syndrome (ascites and pleural effusion due to benign ovarian neoplasms) is a rare cause of ascites formation. Most cases of ascites caused by ovarian disease are from peritoneal carcinomatosis. Ascites with myxedema is secondary to hypothyroidism-related cardiac failure. Mixed ascites occurs in about 5% of cases when the patient has two or more separate causes of ascites formation, such as cirrhosis and infection or malignancy. A clue to the presence of a second cause is an inappropriately high white cell count in the ascitic fluid.

Clinical presentation

History

The history can help to elucidate the cause of ascites formation. Increasing abdominal girth from ascites may be part of the initial presentation of patients with alcoholic liver disease; however, the laxity of the abdominal wall and the severity of underlying liver disease suggest that the condition can be present for some time before it is recognized. Patients who consume ethanol only intermittently may report cyclic ascites, whereas patients with nonalcoholic disease usually have persistent ascites. Other risk factors for viral liver disease should be ascertained (i.e. drug abuse, sexual exposure, blood transfusions, and tattoos). A positive family history of liver disease raises the possibility of a heritable condition (e.g. Wilson disease, hemochromatosis, or α1-antitrypsin deficiency) that might also present with symptoms referable to other organ systems (diabetes, cardiac disease, joint problems, and hyperpigmentation with hemochromatosis; neurological disease with Wilson disease; pulmonary complaints with α1-antitrypsin deficiency). Patients with cirrhotic ascites may report other complications of liver disease, including jaundice, pedal edema, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, or encephalopathy. The patient with long-standing, stable cirrhosis who abruptly develops ascites should be evaluated for possible hepatocellular carcinoma.

Information concerning possible nonhepatic disease should be obtained. Weight loss or a prior history of cancer suggests possible malignant ascites, which may be painful and produce rapid increases in abdominal girth. A history of heart disease raises the possibility of cardiac causes of ascites. Some alcoholics with ascites have alcoholic cardiomyopathy rather than liver dysfunction. Obesity, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia are risk factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, which can cause cirrhosis on its own or can act synergistically with other insults (e.g. alcohol, hepatitis C). Tuberculous peritonitis usually presents with fever and abdominal discomfort. Patients with nephrotic syndrome usually have anasarca. Patients with rheumatological disease may have serositis. Patients with ascites associated with lethargy, cold intolerance, and voice and skin changes should be evaluated for hypothyroidism.

Physical examination

Ascites should be distinguished from panniculus, massive hepatomegaly, gaseous overdistension, intra-abdominal masses, and pregnancy. Percussion of the flanks can be used to determine rapidly if a patient has ascites. The absence of flank dullness excludes ascites with 90% accuracy. If dullness is found, the patient should be rolled into a partial decubitus position to test whether there is a shift in the air–fluid interface determined by percussion (shifting dullness). The fluid wave has less value in detecting ascites. The puddle sign detects as little as 120 mL of ascitic fluid but it requires the patient to assume a hands-and-knees position for several minutes and is a less useful test than flank dullness.

The physical examination can help to determine the cause of ascites. Palmar erythema, abdominal wall collateral veins, spider angiomas, splenomegaly, and jaundice are consistent with liver disease. Large veins on the flanks and back indicate blockage of the inferior vena cava that is caused by webs or malignancy. Masses or lymphadenopathy (e.g. Sister Mary Joseph nodule, Virchow node) suggest underlying malignancy. Distended neck veins, cardiomegaly, and auscultation of an S3 or pericardial rub suggest cardiac causes of ascites, whereas anasarca may be observed with nephrotic syndrome.

Additional testing and diagnostic investigations

Blood and urine studies

Laboratory blood studies can provide clues to the cause of ascites. Abnormal levels of aminotransferases, alkaline phosphatase, and bilirubin are seen with liver disease. Prolonged prothrombin time and hypoalbuminemia are also observed with hepatic synthetic dysfunction, although low albumin levels are noted with renal disease, protein-losing enteropathy, and malnutrition. Hematological abnormalities, especially thrombocytopenia, suggest liver disease. Renal disease may be suggested by electrolyte abnormalities or elevations in blood urea nitrogen and creatinine. Urinalysis may reveal protein loss with nephrotic syndrome or bilirubinuria with jaundice. Specific tests (e.g. α-fetoprotein) or serological tests (e.g. antinuclear antibody) may be ordered for suspected hepatocellular carcinoma or immune-mediated disease, respectively.

Ascitic fluid analysis

Abdominal paracentesis is the most important means of diagnosing the cause of ascites formation. It is appropriate to sample ascitic fluid in all patients with new-onset ascites, as well as in all those admitted to hospital with ascites, because there is a 10–27% prevalence of ascitic fluid infection in the latter group. Paracentesis is performed in an area of dullness either in the midline between the umbilicus and symphysis pubis, because this area is avascular, or in one of the lower quadrants. Needles should not be inserted close to abdominal wall scars with either approach because of the high risk for bowel perforation; puncture sites too near the liver or spleen should be avoided as well. In 3% of cases, ultrasound guidance may be needed. The needle is inserted using a Z-track insertion technique to minimize postprocedure leakage, and 25 mL or more of ascitic fluid is removed for analysis.

Analysis of ascitic fluid should begin with gross inspection. Most ascitic fluid from portal hypertension is yellow and clear. Cloudiness raises the possibility of infectious processes, whereas a milky appearance is seen with chylous ascites. A minimum density of 10,000 erythrocytes per μL is required to provide a red tint to the fluid, which raises the possibility of malignancy if the paracentesis is atraumatic. Pancreatic ascitic fluid is tea colored or black. The ascitic fluid cell count is the most useful test. The upper limit of the neutrophil cell count is 250 cells per μL, even in patients who have undergone diuresis. If paracentesis is traumatic, only 1 neutrophil per 250 erythrocytes and 1 lymphocyte per 750 erythrocytes can be attributed to blood contamination. With spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), the neutrophil count exceeds 250 cells per μ

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree