Nephrotic syndrome

Malnutrition

Congestive heart failure

Urinalysis, 24-h urinary protein

Clinical setting

Clinical setting

Pregnancy

Malignant disease

GGT, 5′-NT

Alkaline phosphatase electrophoresis

Muscle disorders

Creatine kinase, aldolase

Sepsis

Ineffective erythropolesis

“Shunt” hyperbilirubinemia

Clinical setting, cultures

Peripheral smear, urine bilirubin, hemoglobin electrophoresis, bone marrow examination

Clinical setting

GGT, γ-glutamyltransferase; MB-CPK, MB Isoenzyme of creatine phosphokinase; 5′-NT, 5′-nucleotidase; SLAP, serum leucine aminopeptidase.

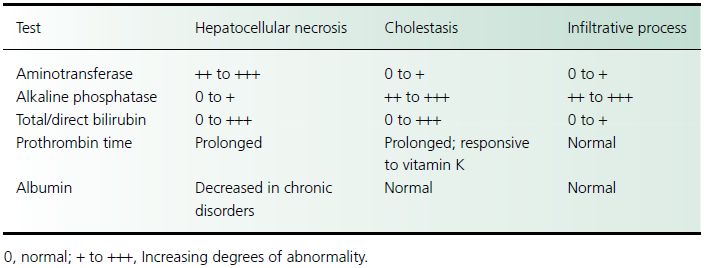

Table 13.2 Routine biochemical tests in the patient with idealized hepatobiliary disease

Disorders with hepatocellular injury

Hepatocellular injury may result from a diverse group of diseases. Acute viral hepatitis in the United States most commonly results from infection with hepatitis A or B, or, less commonly, C viruses. Hepatitis D complicates the course of infection in chronic hepatitis B carriers. Hepatitis E occurs primarily in developing countries, where it is well recognized as a cause of fulminant hepatic failure, particularly in pregnant women. Other viral causes of hepatitis include cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, Epstein–Barr virus, and varicella zoster virus. Chronic infection with either hepatitis B or C viruses may also produce chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis. Chronic ethanol consumption produces a broad range of liver diseases, including fatty liver, alcoholic hepatitis, and cirrhosis. Hereditary liver diseases that produce hepatocellular injury are Wilson disease, hemochromatosis, and α1-antitrypsin deficiency. Congestive and ischemic disease in the liver is caused by congestive heart failure, constrictive pericarditis, hypotension, portal vein thrombosis or hepatic vein outflow obstruction from Budd–Chiari syndrome, inferior vena cava occlusion, or veno-occlusive disease. Significant liver disease during pregnancy, such as acute fatty liver of pregnancy and hepatocellular damage secondary to toxemia, usually occurs in the third trimester. Medication-induced and toxin-induced causes of injury are very common and require a high index of suspicion and careful questioning.

Infiltrative diseases

Malignant diseases, including primary tumors (e.g. hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma), metastases, lymphoma, and leukemia, may produce infiltrative liver disease. Granulomatous liver infiltration may result from infections (e.g. tuberculosis, histoplasmosis), sarcoidosis, and numerous medications.

Clinical presentation

History

An accurate history is critical for a patient whose laboratory studies provide evidence of liver disease. The presenting symptoms provide important diagnostic clues. Pruritus is a common and early symptom in patients with cholestasis. Although classically associated with PBC and primary sclerosing cholangitis, pruritus also is reported in extrahepatic biliary obstruction and hepatocellular disease. Many conditions that produce abnormal liver chemistry levels are painless, but acute biliary obstruction from stones can produce intense right upper quadrant pain. Concurrent high fever raises concern for cholangitis. Acute hepatitis produces less well-defined right upper quadrant discomfort with profound fatigue, whereas hepatic tumors may cause subcostal aching.

A family history is useful in diagnosing and evaluating hereditary hemolytic states, benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis, hemochromatosis, Wilson disease, and α1-antitrypsin deficiency. Exposure to ethanol and industrial and environmental toxins should be identified. A detailed medication history, including over-the-counter and herbal remedies, is critical. In particular, the use of episodic or intermittent medications, such as steroid tapers for asthma or antibiotics, may require specific questioning. Alcoholic patients should be questioned about acetaminophen use because hepatotoxicity can occur in these persons with therapeutic dosing as a result of cytochrome P450 induction. Intravenous drug abuse, sexual contact, and blood transfusions are associated with a risk for viral hepatitis B or C, whereas sudden worsening of liver chemistry levels in a chronic hepatitis B carrier suggests possible hepatitis D superinfection. Waterborne outbreaks of viral hepatitis have been reported in South East Asia and India, underscoring the importance of obtaining a travel history. Risk factors for hepatitis A include recent ingestion of raw or undercooked oysters or clams, male homosexuality, or exposure through day care.

Other diseases associated with liver disorders should be ascertained. Right-sided congestive heart failure, hypotension, and shock are recognized causes of abnormal liver chemistry findings. Chronic pancreatitis may produce abnormal liver tests as a result of stenosis of the common bile duct. Primary sclerosing cholangitis affects 10% of patients with inflammatory bowel disease, in particular those with ulcerative colitis. Obesity, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and corticosteroid use are risk factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hematological disorders (e.g. polycythemia rubra vera, myeloproliferative disorders, and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria) associated with hypercoagulable states predispose to hepatic vein thrombosis. Hemoglobinopathies (e.g. sickle cell anemia, thalassemia) lead to pigment stone formation. Rashes, arthritis, renal disease, and vasculitis may develop with viral hepatitis. The presence of hypogonadism, heart disease, and diabetes suggests possible hemochromatosis. Concurrent lung disease may occur with α1-antitrypsin deficiency, and central nervous system findings are associated with Wilson disease. Patients with leptospirosis will present with hepatic and renal abnormalities. Renal cell carcinoma manifests as abnormal liver chemistry levels in the absence of metastases. Recent surgery should be noted because anesthetic exposure, perioperative hypotension, and blood transfusions all may affect the liver. Recent biliary tract surgery raises concern for bile duct stricture. Cirrhosis is a late complication of jejunoileal, but not gastric, bypass surgery for morbid obesity.

Physical examination

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree