Most endoscopists, and especially beginners, focus on the individual procedures and have little appreciation of the extensive infrastructure that is now necessary for efficient and safe activity. From humble beginnings in adapted single rooms, most of us are lucky enough now to work in large units with multiple procedure rooms full of complex electronic equipment, with additional space dedicated to preparation, recovery, and reporting.

Endoscopy is a team activity, requiring the collaborative talents of many people with different backgrounds and training. It is difficult to overstate the importance of appropriate facilities and adequate professional support staff, to maintain patient comfort and safety, and to optimize clinical outcomes.

Endoscopy procedures can be performed almost anywhere when necessary (e.g. in an intensive care unit), but the vast majority take place in purpose-designed “endoscopy units.”

Endoscopy units

Details of endoscopy unit design are beyond the scope of this book, but certain principles should be stated.

There are two types of unit. Private clinics (called ambulatory surgical centers in the USA) deal mainly with healthy (or relatively healthy) outpatients, and should resemble cheerful modern dental suites. Hospital units have to provide a safe environment for managing sick inpatients, and also more complex procedures with a therapeutic focus, such as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). The more sophisticated units resemble operating suites. Units that serve both functions should be designed to separate the patient flows as far as possible.

The modern unit has areas designed for many different functions. Like a hotel or an airport (or a Victorian household), the endoscopy unit should have a smart public face (“upstairs”), and a more functional back hall (“downstairs”). From the patient’s perspective, the suite consists of areas devoted to reception, preparation, procedure, recovery, and discharge. Supporting these activities are many other “back hall” functions, which include scheduling, cleaning, preparation, maintenance and storage of equipment, reporting and archiving, and staff management.

Procedure rooms

The rooms used for endoscopy procedures should:

- not be cluttered or intimidating. Most patients are not sedated when they enter, so it is better for the room to resemble a modern dental office, or kitchen, rather than an operating room.

- be large enough to allow a patient stretcher/trolley to be rotated on its axis, and to accommodate all of the equipment and staff (and any emergency team), but also compact enough for efficient function.

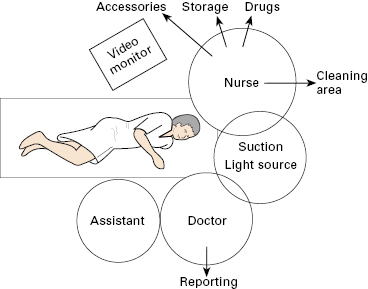

- be laid out with function in mind, keeping nursing and doctor spheres of activity separate (Fig 1.1), and minimizing exposed trailing electrical cables and pipes (best by ceiling-mounted beams).

Each room should have:

- piped oxygen and suction (two lines);

- lighting planned to illuminate nursing activities but not dazzle the patient or endoscopist;

- video monitors placed conveniently for the endoscopist and assistants, but also allowing the patient to view, if wished;

- adequate counter space for accessories, with a large sink or receptacle for dirty equipment;

- storage space for equipment required on a daily basis;

- systems of communication with the charge nurse desk, and emergency call;

- disposal systems for hazardous materials.

Patient preparation and recovery areas

Patients need a private place for initial preparation (undressing, safety checks, intravenous (IV) access), and a similar place in which to recover from any sedation or anesthesia. In some units these functions are separate, but can be combined to maximize flexibility. Many units have simple curtained bays, but rooms with solid side walls and a movable front curtain are preferable. They should be large enough to accommodate at least two people other than the patient on the stretcher, and all of the necessary monitoring equipment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree