Fig. 4.1

Tourniquet

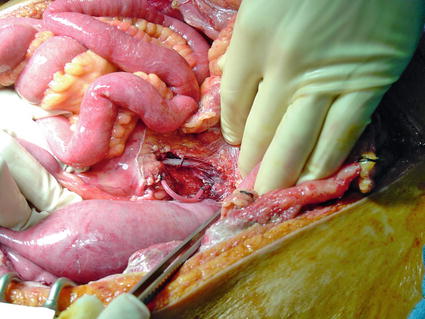

Fig. 4.2

Digital compression used for acute hemorrhage control

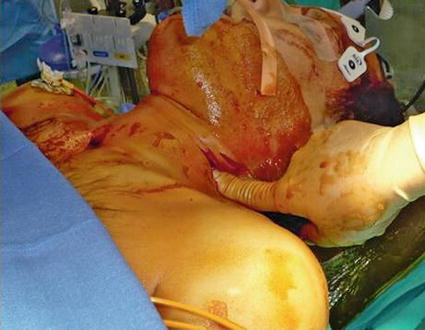

Fig. 4.3

Foley catheter used for bleeding control from subclavian vascular injury

Fig. 4.4

Foley catheter used for subclavian vascular injury

“Blind” application of clamps in a pool of blood, in the hope that the bleeding vessel will be clamped, rarely succeeds, and the risk of iatrogenic damage to adjacent neurovascular structures outweighs the remote possibility of successful bleeding control.

Many victims with vascular injuries reach the emergency room in extremis or cardiac arrest. About 14 % [7] of patients with major abdominal vascular injuries reaching hospital care lose vital signs during transportation or in the emergency room. The role of resuscitative thoracotomy in this group of patients is controversial because of the uniformly poor survival. An emergency room laparotomy is the ultimate and most desperate damage control procedure and may allow temporary bleeding control by direct pressure.

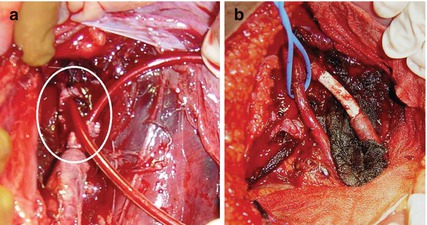

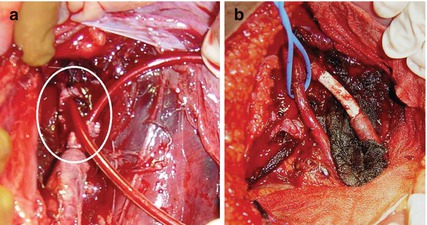

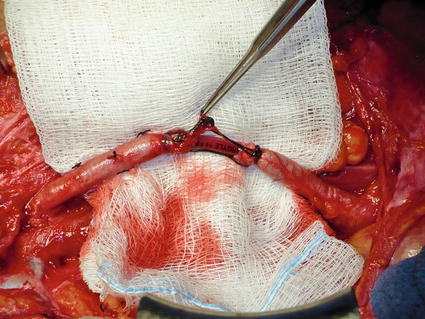

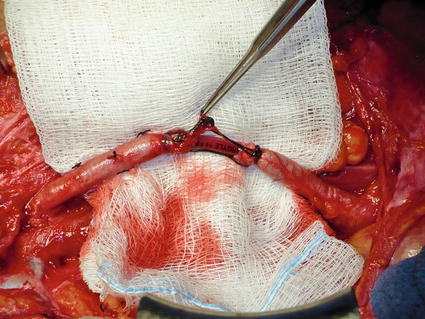

Fig. 4.5

Shunt inserted in the iliac artery as part of damage control (a), and subsequent definitive reconstruction with PTFE (b)

4.4 Operating Room Management

The standard technical principles used in elective vascular surgery may not be applicable in trauma because of the poor physiological condition of the injured patient. The combination of damage control techniques and damage control resuscitation should be considered and applied early. Damage control should be considered in all cases with exhausted physiological reserves at risk of imminent death, in complex injuries requiring special operative skills, in anatomically difficult injuries, in suboptimal environments such as in the battlefield or community hospitals, and if the surgeon is inexperienced with vascular surgery (Table. 4.1). The timing of damage control is critical in determining the outcome. In deciding the timing of the damage control, the surgeon should take into account the nature of the injuries, the physiological condition, age and comorbid conditions of the patient, the hospital capabilities, and his own experience. Damage control should be considered early, ideally before the patient becomes “in extremis” and develops severe coagulopathy, hypothermia, and acidosis. Reserving damage control as a last resort procedure is a common mistake by the inexperienced surgeon and should be avoided because it increases mortality [8].

Table 4.1

Indications for damage control

1. Patients “in extremis” |

2. Difficult surgical access |

3. Community or rural hospitals |

4. Battlefield surgery |

5. Inexperienced surgeons |

The surgeon has many damage control techniques options in his armamentarium. These techniques include temporary intraluminal shunt insertion, ligation, simple repair, balloon catheter occlusion, and extremity amputation. Complex repairs, such as end-to-end anastomosis or graft interposition should be undertaken at a later stage, after resuscitation and correction of coagulopathy, hypothermia, and acidosis.

Temporary intraluminal shunt placement (Figs. 4.5 and 4.6) is the most commonly used vascular damage control procedure. These shunts were initially used in cases with combined orthopedic trauma to allow distal perfusion during bone fixation. The technique was subsequently used as part of damage control to shorten the operative procedure and provide continuous blood supply to critical tissues during the resuscitation period. Any appropriate size sterile tubing may be used for shunt purposes. Following proximal and distal vessel clot removal with a Fogarty catheter and local irrigation with heparinized saline, the shunt is placed intraluminally and secured in place with ties. The vessel ends should not be trimmed as all tissue distal to the ties will ultimately be sacrificed. The shunt should be adequately size matched, and care should be taken to not injure the intima during placement. Routine systemic heparinization is not required and should be avoided in the coagulopathic patient requiring damage control. Temporary shunts have been used in the neck, the upper extremity, the lower extremity, and the abdomen. In rare occasions a shunt may be used in common or external iliac venous injuries to reduce bleeding from the extremity due to venous congestion. Postoperatively, the shunt should be closely monitored for signs of occlusion, which may occur after correction of the existing coagulopathy. Loss of peripheral pulse, a temperature discrepancy between extremities, or deteriorating lactic acidosis in patients with visceral artery shunts should prompt the surgeon to return to the operating room to reassess the patency of the shunt. Planned reoperation and definitive reconstruction of the injured vessel, with an autologous vein or PTFE graft, should be done as soon as the coagulopathy, hypothermia, and acidosis are corrected, usually within 24–36 h after the damage control operation (Fig. 4.5).

Fig. 4.6

Right external iliac artery intraluminal damage control shunt, 14 Fr Argyle

Ligation of the injured vessel is another option in damage control procedures. This approach should be avoided with major arteries because there is a possibility for catastrophic consequences to occur. Ligation of the common or internal carotid artery very often leads to massive stroke and death. Ligation of proximal extremity arteries (subclavian, axillary, and brachial artery in the upper extremity, external iliac, and common and superficial femoral and popliteal arteries in the lower extremity) is poorly tolerated by most patients and is usually associated with a high incidence of limb loss. Any attempts to revascularize the extremity at a later stage may cause severe reperfusion injury and organ failure or death. In these cases, a temporary intraluminal shunt should be considered instead of ligation.

Ligation of the proximal superior mesenteric artery (SMA) results in ischemic necrosis involving the small bowel and the right colon. The first 10–20 cm of the jejunum may survive via collaterals from the superior pancreaticoduodenal artery. Ligation should be avoided because of the catastrophic consequences of short bowel syndrome. For patients in critical condition, a damage control procedure with a temporary endoluminal shunt and subsequent definitive reconstruction with an autologous vein should be considered (Fig. 4.7). Ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery is well tolerated, and no cases of colorectal ischemia have been reported in trauma.