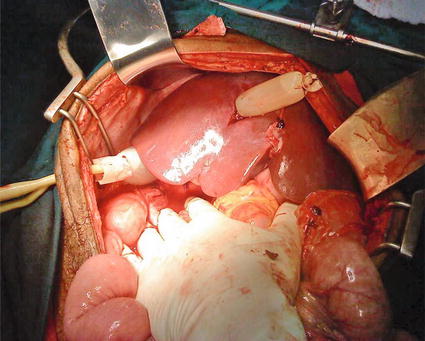

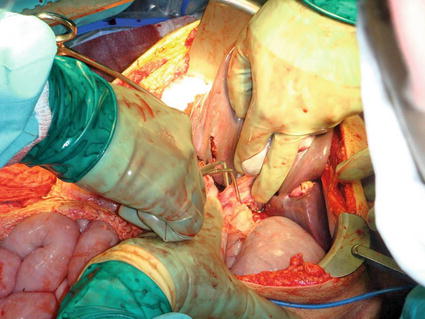

Fig. 8.1

The liver is packed with laparotomy pads to provide compression against the abdominal wall, diaphragm, and retroperitoneum

Once the liver is packed, the abdomen is rapidly but systematically explored for other sources of hemorrhage and hollow viscus injuries. These are controlled as needed, and the sites of hemorrhage are prioritized.

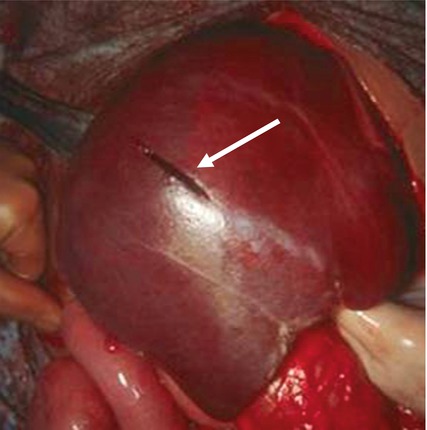

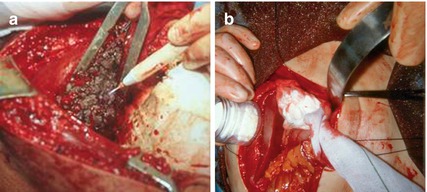

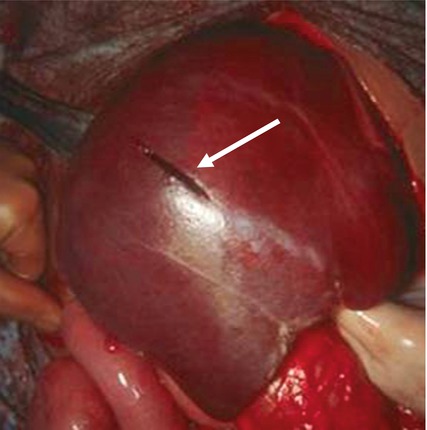

Grade I–II lacerations (see Table 8.1) [10] may stop bleeding spontaneously or after a short period of packing (Fig. 8.2). Ongoing hemorrhage can usually be controlled with electrocautery or argon beam coagulation, with or without application of topical hemostatic agents such as microcrystalline collagen, fibrin glue, or other agents (Fig. 8.3).

Grade | Injury description | |

|---|---|---|

I | Hematoma | Subcapsular, <10 % surface area |

Laceration | <1 cm parenchymal depth | |

II | Hematoma | Subcapsular, 10–50 % surface area; intraparenchymal, <10 cm diameter |

Laceration | 1–3 cm parenchymal depth, <10 cm length | |

III | Hematoma | Subcapsular, >50 % surface area or expanding; intraparenchymal, >10 cm diameter or expanding, or ruptured |

Laceration | >3 cm parenchymal depth | |

IV | Laceration | Parenchymal disruption involving 25–75 % of hepatic lobe or 1–3 Couinaud’s segments in a single lobe |

V | Laceration | Parenchymal disruption involving >75 % of hepatic lobe or >3 Couinaud’s segments in a single lobe |

Vascular | Juxtahepatic venous injuries | |

VI | Vascular | Hepatic avulsion |

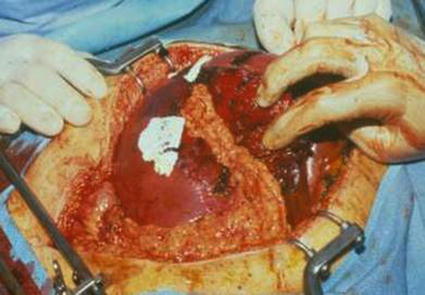

Fig. 8.2

Low-grade lacerations (arrow) may often stop bleeding spontaneously or following a brief period of compression or packing

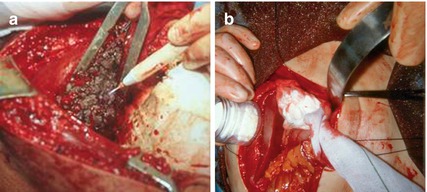

Fig. 8.3

Low-grade injuries may be treated by topical hemostatic techniques such as argon beam coagulation (a) or microcrystalline collagen application (b)

In the physiologically compromised patient, the decision to pursue damage control must be made early in order to optimize the patient’s chance of survival [11]. Time-consuming efforts to stop relatively minor bleeding should not distract the surgeon from the primary objective. The liver should be packed quickly and other damage control maneuvers completed prior to a temporary abdominal closure. In order to facilitate later pack removal without disrupting clot, a nonadherent plastic drape may be spread over the liver surface, with the packs placed on top of the plastic.

If the patient’s condition allows, the liver should be examined to determine the extent of the injury. Grade II–III lacerations should be inspected to determine whether a discrete vessel may be ligated. Otherwise, bleeding can generally be controlled by packing the wound with an omental pedicle (Fig. 8.4) or a plug of topical hemostatic agents such as absorbable gelatin sponge wrapped in oxidized regenerated cellulose. Suture hepatorrhaphy is an option, but one must avoid leaving a large dead space and avoid devitalizing tissue or lacerating vessels or bile ducts.

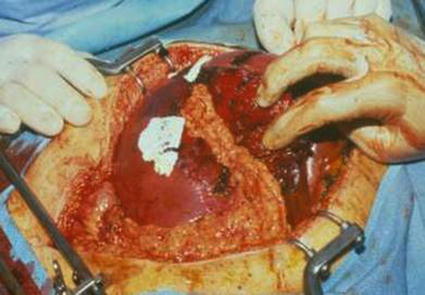

Fig. 8.4

Omental pedicle packing may provide hemostasis for deeper injuries

Bleeding that persists despite packing may be arterial in origin. The Pringle maneuver—i.e., control of the hepatoduodenal ligament with a Rumel tourniquet or vascular clamp—should be employed (Fig. 8.5). If this controls hemorrhage, it is likely that the bleeding is from either a hepatic arterial branch or major branch of the portal vein. This cannot be left in place for a prolonged period, so definitive maneuvers must be undertaken, and the clamp should be released within 60 min if possible. Ligation of the right or left hepatic artery may control the bleeding. Alternatively, in the appropriate setting, the patient may undergo arterioembolization.

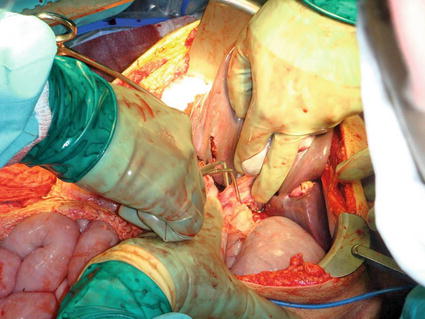

Fig. 8.5

The Pringle maneuver: a vascular clamp is applied to the hepatoduodenal ligament

Extensive lacerations may need to be explored to control major vessels. The finger fracture technique allows one to reach major vessels for ligation. Stapling devices can also be useful in dividing the hepatic parenchyma to reach deep vessels. Transhepatic penetrating wounds may leave a long intraparenchymal defect that is difficult to access for vascular control. Dividing extensive hepatic parenchyma may not be practical. Balloon tamponade can be achieved by securing a red rubber catheter inside a penrose drain and passing it through the wound. The penrose drain is inflated with saline to control hemorrhage [12]. The drain and catheter are passed through the abdominal wall for later removal (Fig. 8.6).