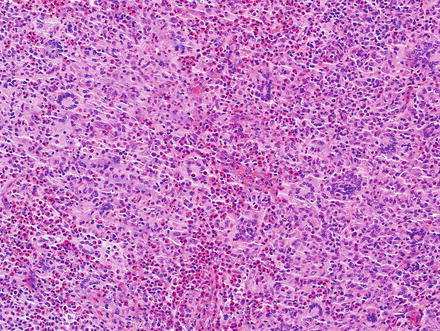

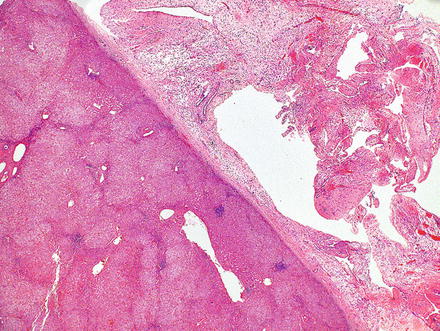

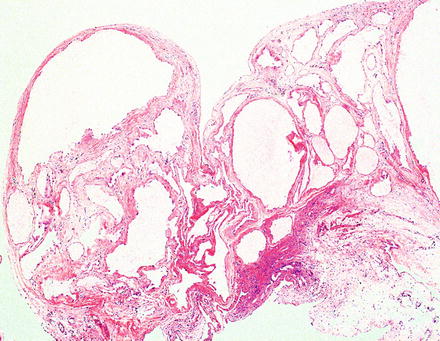

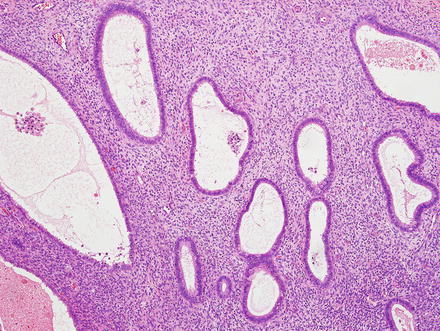

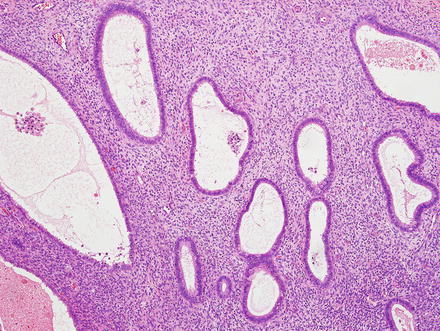

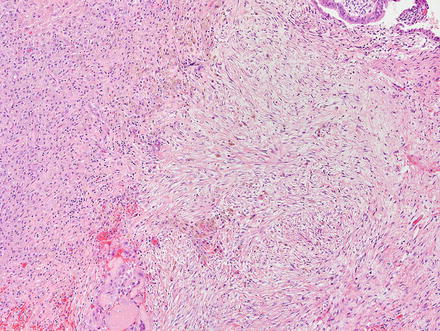

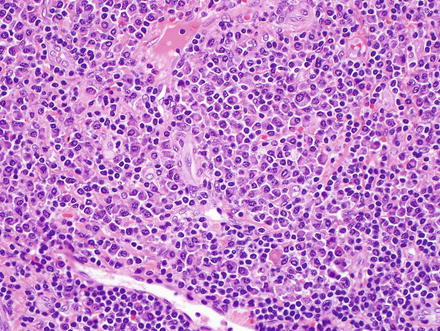

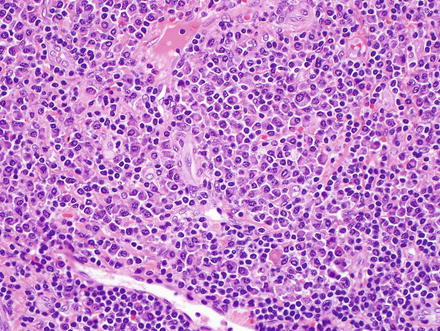

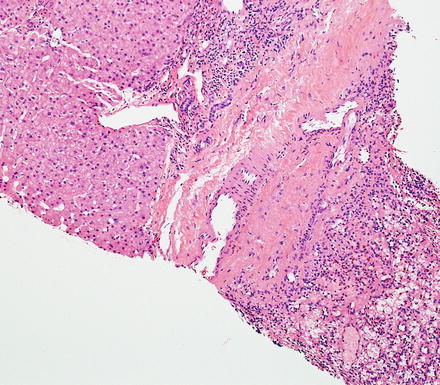

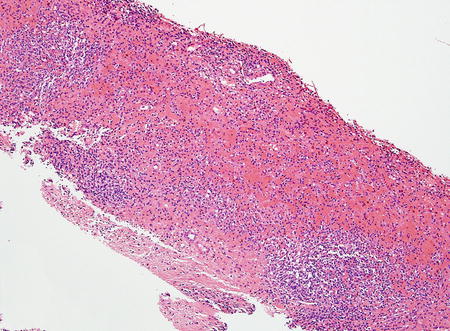

Fig. 1.1

Accessory hepatic lobe. The accessory lobe is attached to the liver by a pedicle of fibrovascular tissue

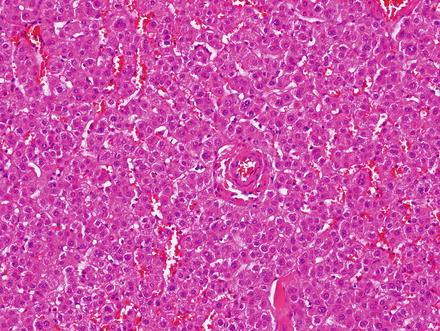

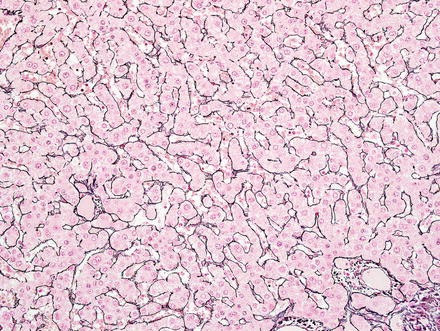

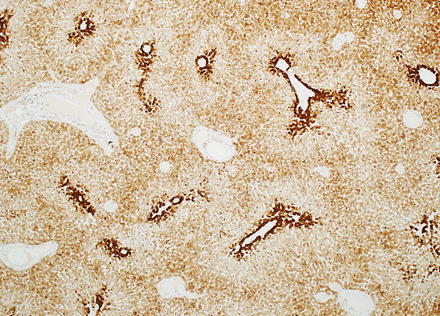

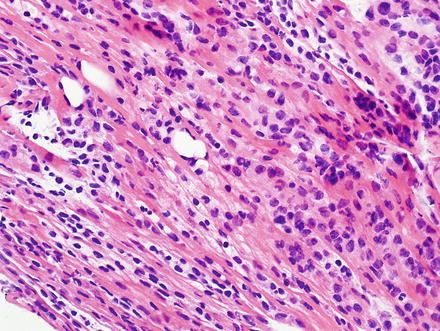

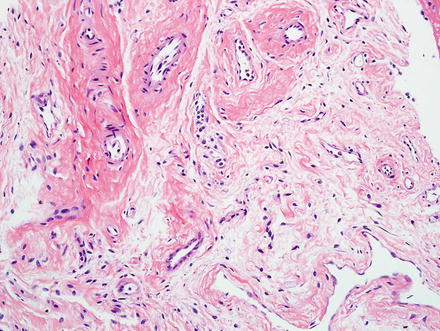

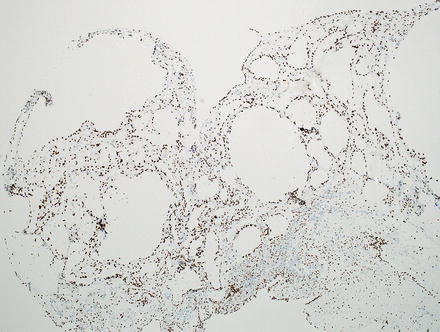

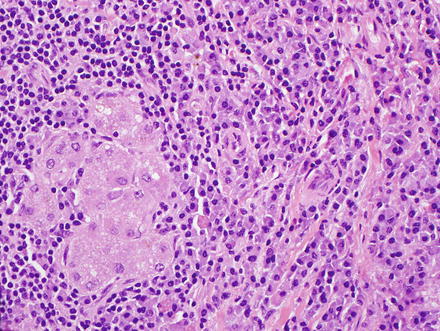

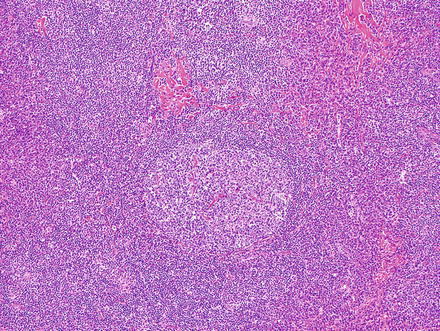

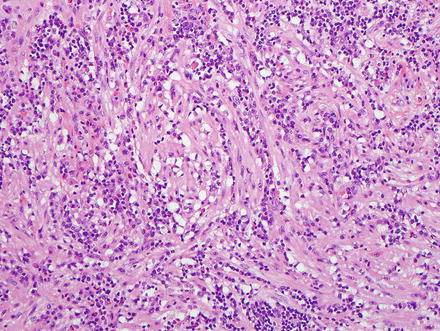

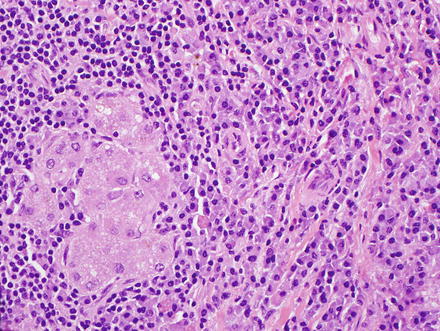

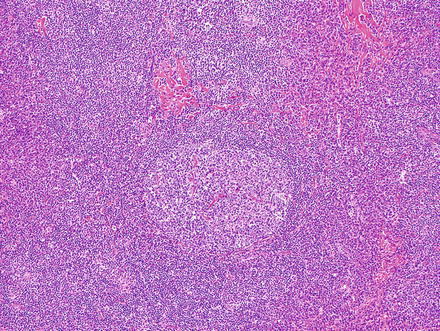

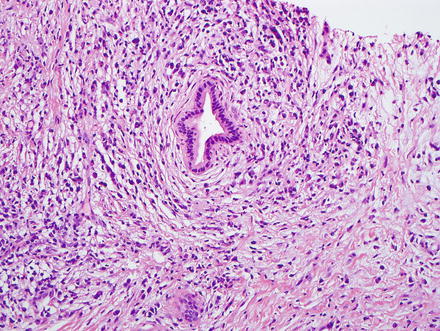

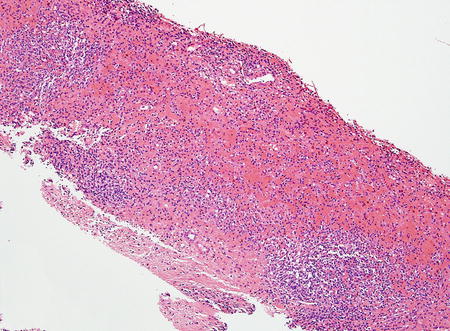

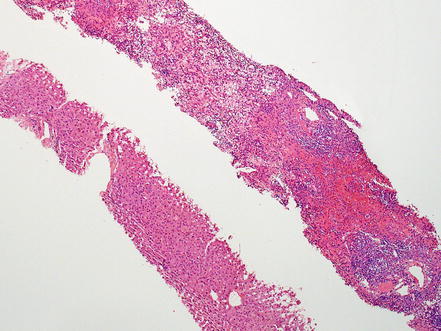

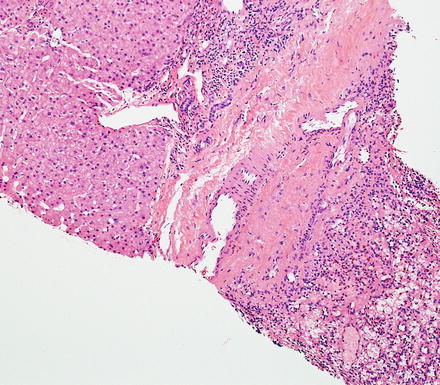

Accessory lobes can measure up to 19 cm [2]. They can become symptomatic due to large size or torsion [1, 2, 4, 5]. Grossly, the cut surface has the appearance of normal liver. Histologically, accessory lobes demonstrate normal liver architecture. However, some vascular abnormalities are common, including aberrant naked arteries (Fig. 1.2). Accessory lobes also often contain mild portal inflammation and bile ductular proliferation. Necrosis or post-necrotic fibrosis can occur in cases of torsion and subsequent infarction [2]. They have a normal reticulin framework (Fig. 1.3) and most have a normal glutamine synthetase-staining pattern (Fig. 1.4). However, some cases will have sufficient abnormalities in their blood flow that they can develop findings that resemble some features of focal nodular hyperplasia, including vague nodularity and abnormal glutamine synthetase staining.

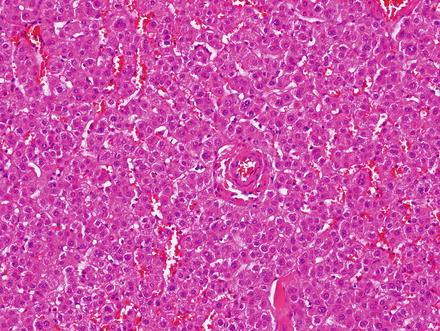

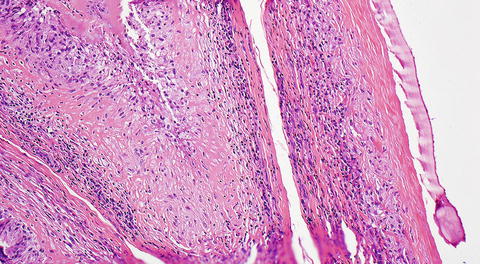

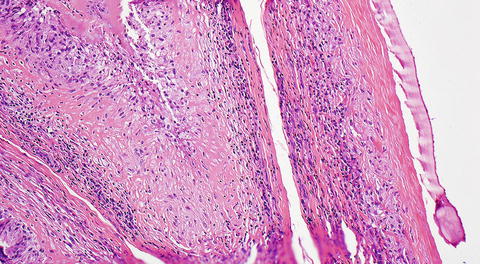

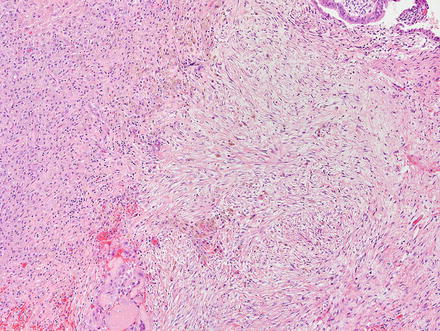

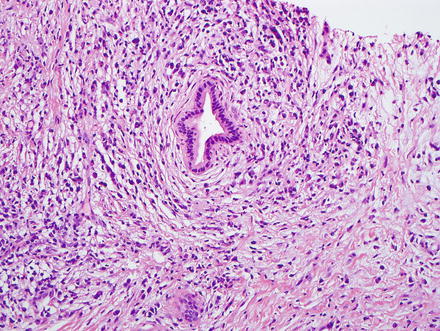

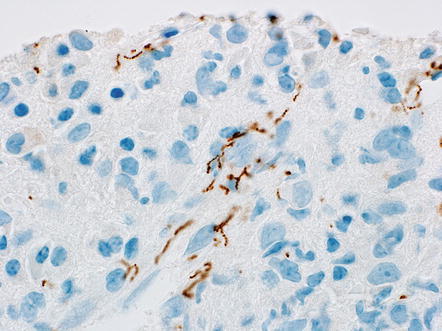

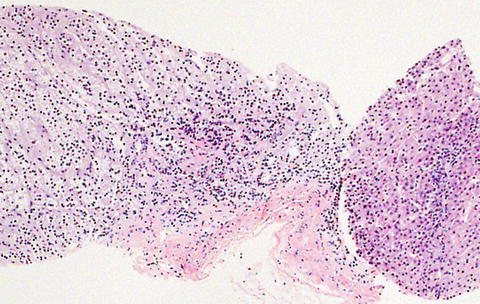

Fig. 1.2

Accessory hepatic lobe. The accessory lobe consists of essentially normal liver parenchyma, though aberrant naked arteries can sometimes be found

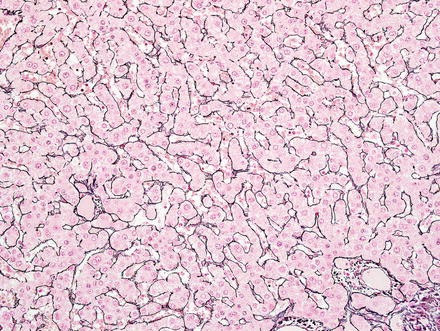

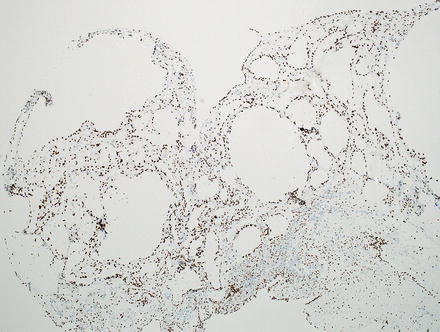

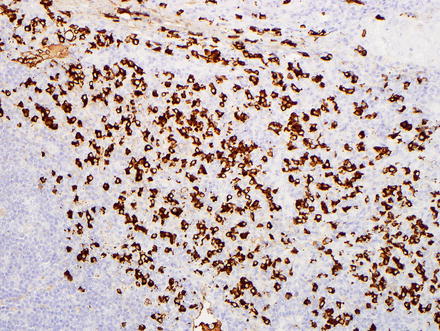

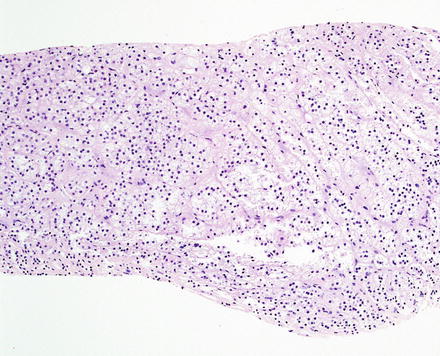

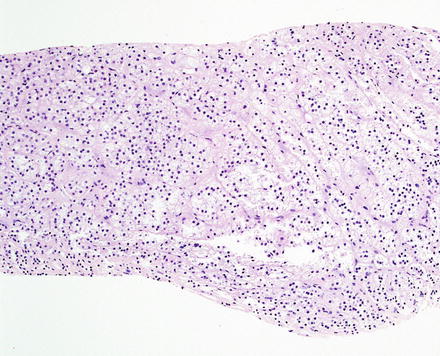

Fig. 1.3

Accessory hepatic lobe. A reticulin stain shows an intact reticulin meshwork

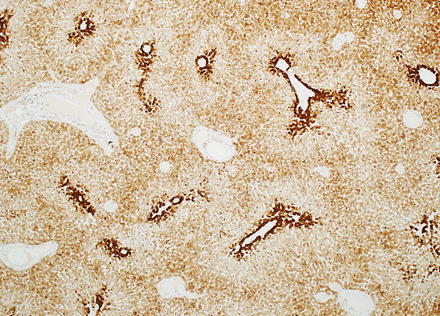

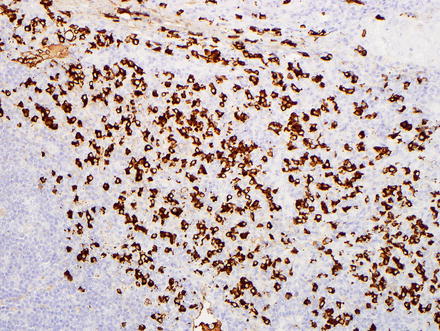

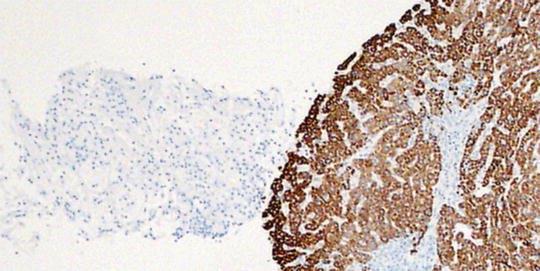

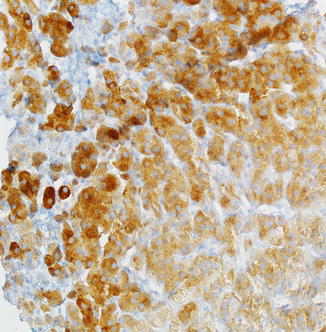

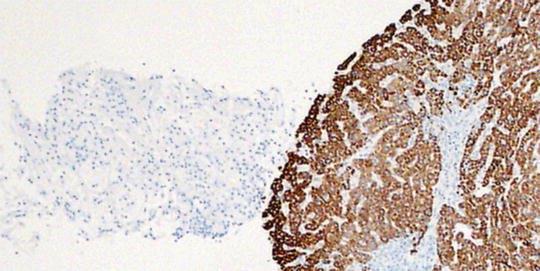

Fig. 1.4

Accessory hepatic lobe. A gluthamine synthetase immunostain shows a normal pattern of zone 3 expression

Riedel’s lobe of the liver is a variant of the hepatic accessory lobe that consists of a tongue-like caudal projection from the right lobe of the liver. This can produce a palpable mass in the right upper abdominal quadrant. Most patients are women, ranging in age between 31 and 77 years [6]. Other variants include intra-thoracic accessory hepatic lobes, which have vascular supplies that perforate the diaphragm [7], and can sometimes mimic a pulmonary tumor [8, 9].

Accessory lobes occasionally require surgical treatment because of their large size, torsion, or the presence of other associated defects. At other times, they are resected as potential neoplasms, when the diagnosis is not clear from imaging studies. Benign and malignant lesions such as focal nodular hyperplasia, hepatocellular adenoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma can rarely arise in accessory lobes [10, 11].

1.2 Benign Cystic Mesothelioma

Benign cystic mesotheliomas are relatively rare benign tumors that occur mainly in young women, but they can occur in both genders and any age [12–14]. Synonyms include inflammatory inclusion cyst of the peritoneum, multilocular peritoneal inclusion cyst, and multicystic mesothelial proliferation. They most often arise in the pelvic peritoneum, usually in the tubo-ovarian region, but secondary serosal involvement of other organs has been reported (uterus, kidney, bladder, liver, and colon) [13, 15, 16]. Involvement of the liver is very rare [13–16].

While some authors regard this lesion as a true neoplasm, most authorities consider cystic mesothelioma to represent a reactive mesothelial proliferation [15–17]; this is supported by the presence in most cases of identifiable inciting agents, such as previous surgery, pelvic inflammation, endometriosis, or other forms of mesothelial irritation [15, 16]. A hormonal association is suggested by the female predominance and only rare occurrence after menopause [14]. The prognosis of benign cystic mesothelioma is excellent [15, 16], but there can be local recurrence [14].

Benign cystic mesothelioma can range from a small and localized lesion to a diffuse multifocal process [15, 16]. It is typically asymptomatic, but can sometimes present as a palpable mass, with ascites, or constipation [13, 15]. Radiologically, the lesion can be highly vascular and mimic focal nodular hyperplasia or hepatocellular carcinomas [14]. Liver involvement can be accompanied by involvement of other organs such as the pelvic or inguinal region, or rarely the pericardium [18, 19].

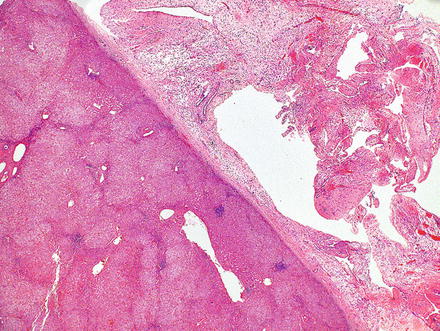

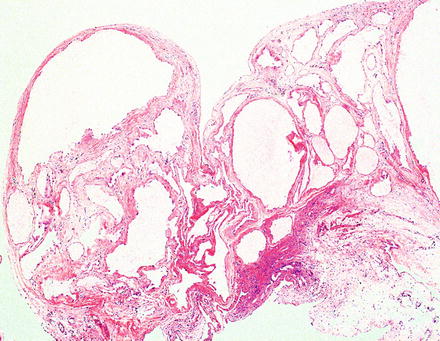

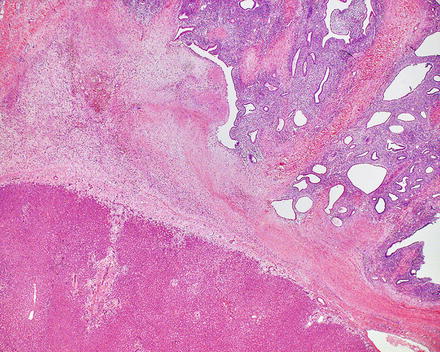

Grossly, the tumors are located in the liver immediately beneath the Glisson capsule (Fig. 1.5) and can measure up to 10 cm. They are typically encapsulated and have a soft glistening surface and a cystic (microcystic and macrocystic) configuration [14]. The cysts often contain a gelatinous fluid [14, 18].

Fig. 1.5

Benign multicystic mesothelioma. This lesion has a subcapsular location

Microscopically, the lesion is partially cystic, encapsulated, and features high vascularity. The cysts are lined by flattened cells (Fig. 1.6) with bland, oval to spindled nuclei, sometimes with a hobnail appearance. In addition to the cysts, the lesion contains tubular and gland-like spaces, anastomosing loose cords, as well as areas with solid, reticulated nests of epithelioid cells (Fig. 1.7). The tubular and glandular structures are lined by epithelioid cells with clear, vacuolated cytoplasm. The tumor cells have indented/cleaved nuclei that are moderately pleomorphic and have small rims of cytoplasm. A fibrous stroma featuring a rich vascular proliferation (medium-to large-sized vessels) is interspersed between the cystic spaces (Fig. 1.8). Hemorrhage is often widespread in the lesion. This, along with the overall high tumor vascularity, can mimic a vascular neoplasm [14, 18].

Fig. 1.6

Benign multicystic mesothelioma. The lesion is characterized by cystic spaces lined by flattened mesothelial cells

Fig. 1.7

Benign multicystic mesothelioma. In some cases, there may be focal areas of compact growth

Fig. 1.8

Benign multicystic mesothelioma. A loose fibrous stroma rich in blood vessels is interspersed between the cystic spaces

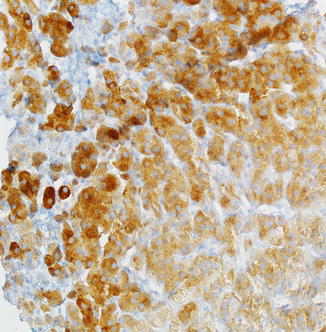

By immunohistochemistry, the lesional cells are positive for keratin, CAM 5.2, HBME-1, D2-40, calretinin, WT-1 (Fig. 1.9), EMA, and CK5/6. Approximately 30 % of tumors show nuclear positivity for estrogen receptor. The proliferative index is less than 1 %. Ultrastructural analysis confirms mesothelial differentiation, characterized by the presence of microvilli and desmosomes [14, 18].

Fig. 1.9

Benign multicystic mesothelioma. The mesothelial cystic lining expresses WT-1

The differential diagnosis includes lymphangioma, which develops in younger individuals and usually spares the pelvis. Furthermore, lymphangiomas are richer in smooth muscle bundles and often contain follicular lymphoid aggregates. By immunostains, lymphangiomas express D2-40, CD31, and CD34 and lack mesothelial marker expression. Hemangiomas have a similar immunostain profile to lymphangiomas, which can distinguish them from benign cystic mesothelioma in challenging cases. Another possibility to consider in the differential diagnosis is metastatic cystic variant of clear cell renal cell carcinoma; this is differentiated from benign cystic mesothelioma by a history of a renal mass, the presence of clusters of clear cells within the cyst wall, immunostain expression of keratin, RCC, and PAX-8, and the lack of expression of mesothelial markers. Benign cystic mesotheliomas can be distinguished from malignant mesothelioma by the lack of cytologic atypia and the lack of complex and/or infiltrative growth, low cellularity, and lack of mitotic activity [14, 18].

1.3 Echinococcosis

Echinococcosis is an infectious disease caused by larva of Taeniid cestodes (tapeworms) belonging to the Echinococcus species [20]. The cystic form is also known as “hydatid cyst.” Humans are infected by ingesting Echinococcus eggs, which are excreted by infected animals [20–22].

Echinococcosis has two main forms, a cystic form characterized by large cystic lesions and an alveolar form featuring alveolar structures (1 mm to 3 cm) [23]. Cystic Echinococcosis is most common in temperate zones such as the Mediterranean, Australia, Central Asia, and some parts of America [24], whereas alveolar Echinococcosis is endemic in the northern hemisphere (North America, Asia, China, Japan, and Europe) [21, 25]. The hepatic lesions grow very slowly in the liver (1–5 mm/year). Therefore, the disease remains asymptomatic for long periods of time [23]. Symptoms eventually result from the mass effect exerted by the cyst/alveolar lesions or by cyst rupture, which can lead to anaphylactic shock (intraperitoneal rupture) or secondary cholangitis (rupture into biliary system) [20, 23]. The alveolar form can also lead to liver failure due to infiltrative growth and potential spread to other organs (through rupture into the abdominal cavity or biliary tree) [26, 27].

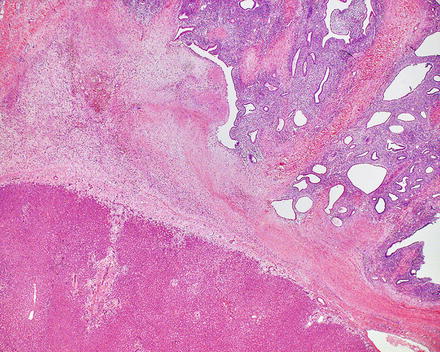

The diagnosis is typically made by ultrasound findings and positive serology [23, 28–30]. Because of this, Echinococcosis-related liver lesions rarely get evaluated by the surgical pathologist. However, there can be atypical imaging findings that lead to biopsies or to resections. In resection specimens, the typical cystic form is characterized by a spherical cyst (Fig. 1.10), measuring up to 30 cm, and has a fibrous rim. The cyst can be unilocular but more frequently contains several daughter cysts, developed by growth and invagination of the germinal membrane.

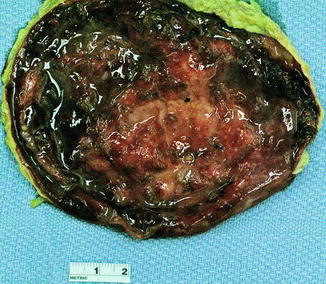

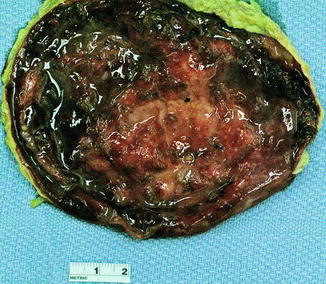

Fig. 1.10

Echinococcal cyst, gross. Grossly, the cystic form of Echinococcosis is characterized by a spherical cyst surrounded by a fibrous rim. Although this example is unilocular, most cases are multilocular, featuring multiple daughter cysts within the main cyst

The cyst wall consists of four layers, though in any given histological section some of the layers may not be apparent.

1.

The outer layer is composed of the host response, which commonly includes a fibrous rim of variable thickness (Fig. 1.11). Eosinophils are not prominent, but if the cyst ruptures they can become more conspicuous, and often are accompanied by granulomas (Fig. 1.12).

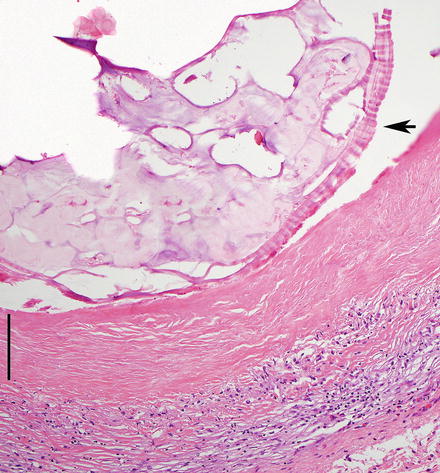

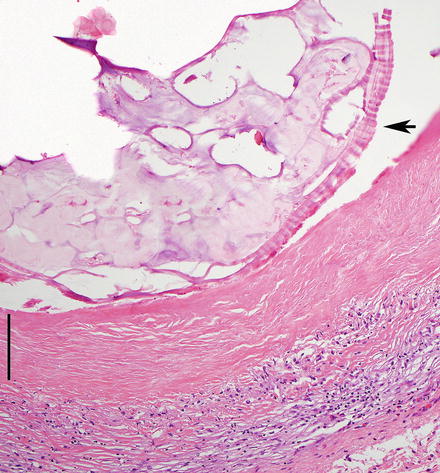

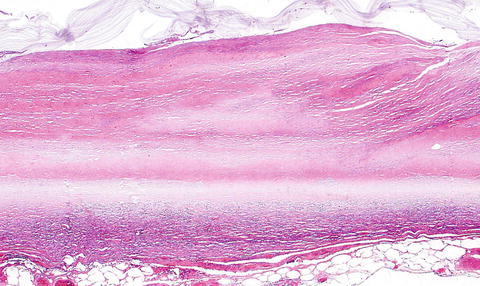

Fig. 1.11

Echinococcal cyst, cyst wall. Microscopically, Echinococcal cysts feature an outer rim of host reaction, an outer anucleated membrane (marked by vertical line), and a germinal layer that often separates upon sectioning (arrow)

Fig. 1.12

Echinococcal cyst, host reaction. The host reaction to Echinococcal cysts (right) can produce granulomatous inflammation (middle and left)

2.

An outer membrane (also called the middle layer) is eosinophilic, anucleated, and laminated and measures approximately 1 mm in thickness (Fig. 1.13). This layer is white, refractile, friable, and slippery to touch. It is positive for PAS and GMS.

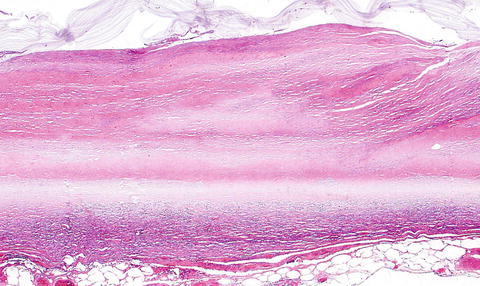

Fig. 1.13

Echinococcal cyst, outer layer. The anucleated laminated membrane is seen

3.

The transparent germinal layer (also called inner layer) measures 10–25 μm in thickness and contains nuclei (Fig. 1.14). This layer gives rise to brood capsules, attached by short stalks, in infectious (fertile) cysts.

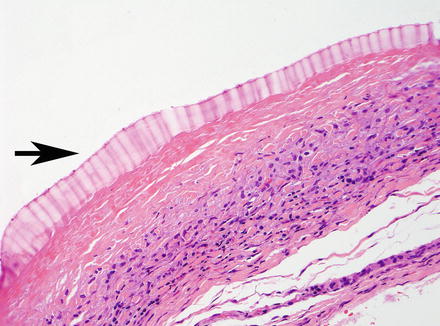

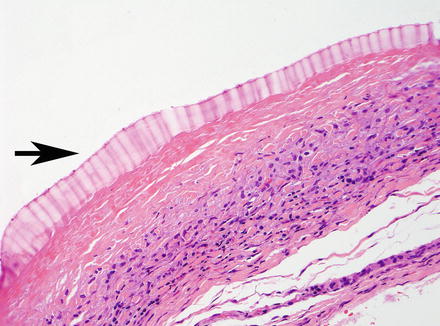

Fig. 1.14

Echinococcal cyst, inner layer. The germinal layer (arrow) is seen as a thin layer on top of the laminated membrane

4.

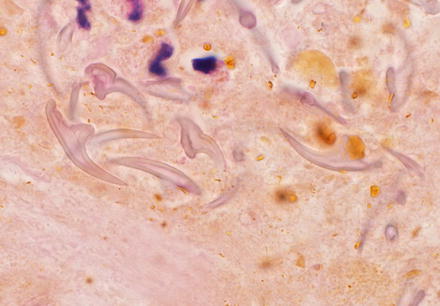

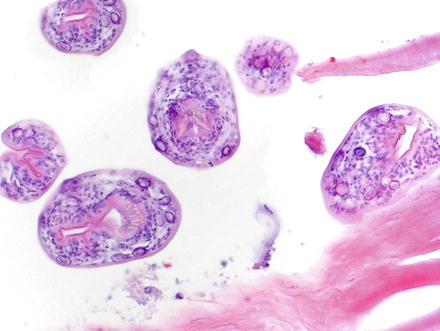

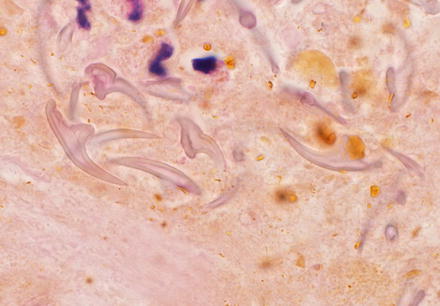

In the center of the cyst, protoscolices (hydatid sand) can sometimes be found, measuring approximately 100 μm each (Fig. 1.15). These are oval structures containing round suckers and refractile, birefringent, acid-fast hooklets. They may not be present in all cases, depending in part on the age of the cyst, extent of sampling, and whether there has been treatment prior to resection. Protoscolices are usually attached to the germinal layer or budding from it. The hooklets are more commonly found and in fact may be the only component seen in many cases, but are diagnostic (Fig. 1.16).

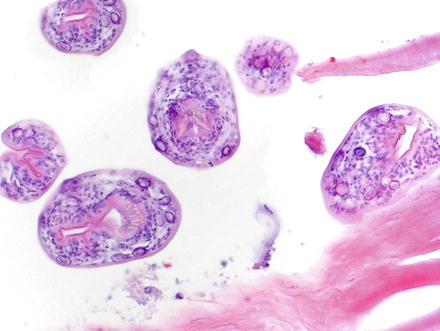

Fig. 1.15

Echinococcal cyst, hydatid sand. Protoscolices are characteristic of Echinococcal cysts. These oval structures contain round suckers and retractile hooklets and are found budding from the germinal layer

Fig. 1.16

Echinococcal cyst, hydatid sand. In many cases, only the hooklets are evident. They are diagnostic of Echinococcus

The alveolar form, on the other hand, features multilocular, necrotic, cystic cavities, containing thick pasty material and lacking a fibrous wall. Histologically, the cysts have a laminated membrane, but no germinal membrane or protoscolices. Hooklets can be found. The laminated membrane is often fragmented; a PAS stain may be necessary to highlight it. The cysts in the alveolar form invade necrotic liver tissue in a manner similar to malignant neoplasms. The host response is variable and may contain a granulomatous reaction with neutrophils and eosinophils, or feature a peripheral rim of extensive necrosis, fibrosis, and calcification.

Mortality from Echinococcosis is uncommon in developed countries, but death rate from Echinococcosis is as high as 5 % worldwide [23, 28, 31]. The treatment of choice for the cystic form is puncture aspiration, injection, and re-aspiration (PAIR), which results in parasitological clearance in 96 % of cases [32]. In this form of treatment, the cysts are aspirated and then re-injected with ethanol or hypertonic saline, which is left in the cyst for a short time before removal by re-aspiration. Treatment of the alveolar form, on the other hand, is similar to treatment for malignancies and consists of radical surgery followed by chemotherapy [20].

1.4 Endometriosis

Endometriosis is a common condition that most frequently involves the pelvis [33]. Endometriosis is rarely found in extra-pelvic locations; and when this occurs, it is termed “atypical endometriosis” [34]. Atypical endometriosis can involve virtually any organ, and intrahepatic endometriosis is one rare form [35]. When there is hepatic involvement, a previous history of endometriosis is present in 67 % of cases [35]. Hepatic endometriosis is not limited to women of reproductive age; 33 % of lesions are described in post-menopausal women [35].

Patients typically present with abdominal pain, but only a small minority of patients (5.5 %) presents with cyclical abdominal pain accompanying the menstrual cycle [35]; this makes the clinical diagnosis extremely difficult. Therefore, diagnosis is almost always dependent on histologic examination. The diagnosis can be very difficult to make on needle biopsy and the diagnosis is not made until the lesion is excised in most cases. Despite its rarity, this entity should be considered in women with recurrent hepatic cysts, regardless of age.

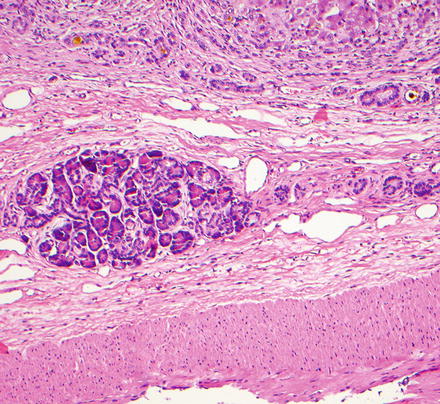

Grossly, hepatic endometriosis is typically cystic and shows hemorrhage, sometimes resembling ovarian chocolate cysts. Histologically (Figs. 1.17 and 1.18), hepatic endometriosis features endometrial glands (or cysts lined by endometrial glandular epithelium), endometrial stroma, and hemorrhage (Fig. 1.19); identifying two of these features is sufficient to render the diagnosis of endometriosis.

Fig. 1.17

Intrahepatic endometriosis. Endometriosis (upper right) involves the hepatic parenchyma (lower left)

Fig. 1.18

Intrahepatic endometriosis. Endometriosis is histologically characterized by endometrial glands and stroma

Fig. 1.19

Intrahepatic endometriosis. Hemosiderin deposition is common

The epithelium has a variable appearance, ranging from flattened to elongated and pseudostratified cells. The endometrial stroma consists of stromal cells with “naked nuclei” surrounded by reticulin fibers and spiral arterioles. The immunohistochemical profile is characterized by positive staining for keratin stains (including CK7) in the epithelium, positive staining for CD10 in the endometrial stroma, and positive staining for ER and PR in both components (Fig. 1.20).

Fig. 1.20

Intrahepatic endometriosis. An immunostain for ER highlights endometrial glands and stroma

The main entity to be considered in the differential diagnosis is mucinous cystic neoplasm of the liver [36]. Both stromal and epithelial elements are distinct; the stroma in mucinous cystic neoplasm is more cellular and resembles ovarian stroma (cellular fibroblast like cells in whirling and storiform patterns) rather than endometrial stroma. The stroma in both lesions is positive for ER and PR, but only the epithelium of endometriosis will be positive for ER and PR, whereas the epithelium of mucinous cystic neoplasms is not. In addition, the epithelial lining is almost always mucinous in mucinous cystic neoplasms and does not resemble endometrial epithelium. In difficult cases, immunostains for CD10 and inhibin can be helpful; the former is positive in the stroma of endometriosis, whereas the latter is positive in the stroma of mucinous cystic neoplasms [36].

1.5 Focal Fatty Nodule

Focal fatty nodules are defined as localized macrovesicular steatosis involving a number of contiguous hepatic lobules, but with otherwise normal liver architecture. This lesion is also known as focal fat infiltration. Focal fatty nodules are usually seen in adults (age range 20–80 years) with a female predominance [37]. They can be large, with some reported cases as large as 12 cm [38]. While most are recognized by radiology, some cases can be challenging [39], leading to targeted biopsies. On fine-needle aspirates, the fat-laden hepatocytes can sometimes resemble signet ring cells, suggesting a diagnosis of metastatic signet ring cell carcinoma [38].

Although this condition can be seen in otherwise normal livers, it has been associated with a variety of conditions including diabetes mellitus, alcoholic liver disease, congestive heart failure, porphyria cutanea tarda, and viral hepatitis. Rarely, it can be associated with acute bleeding [38]. The pathogenesis remains unknown.

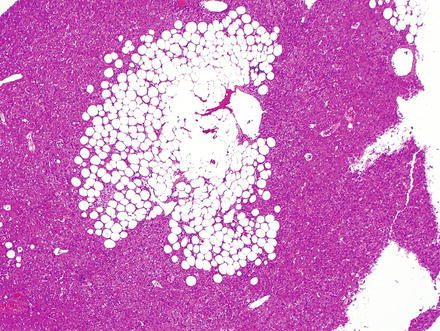

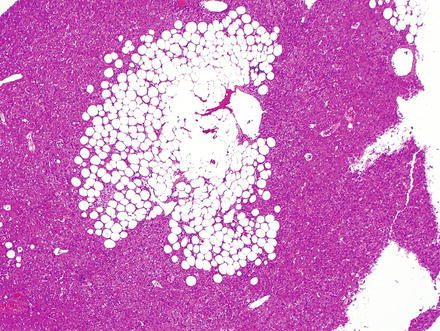

Grossly, focal fatty nodules may be single or multiple and may involve one or both hepatic lobes. They appear as well-demarcated, pale-yellow or yellow-white nodules within the liver parenchyma, ranging in size from less than 1 cm to up to 10 cm. Microscopically, macrovesicular steatosis involves multiple contiguous hepatic acini, which still have recognizable portal tracts and central veins (Fig. 1.21). Occasionally, Mallory bodies may also be seen, especially in subscapular lesions. Primary tumors of the liver need to be carefully excluded, before making the diagnosis of focal fatty nodule, including angiomyolipoma, focal nodular hyperplasia, hepatic adenoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Fig. 1.21

Focal fatty nodule. Macrovesicular steatosis involves the hepatic acinar parenchyma, but normal portal tracts and central veins should be present

1.6 Inflammatory Pseudotumor Including IGG4-Related Disease

Inflammatory pseudotumor is a benign mass-forming lesion that is histologically composed of fibrous tissue, proliferating myofibroblasts, and a prominent inflammatory infiltrate which is composed mostly of plasma cells. Inflammatory pseudotumor has also been described in the literature as plasma cell granuloma, xanthogranuloma, post-inflammatory tumor, inflammatory myofibroblastic lesion, fibroxanthoma, pseudolymphoma, and histiocytoma. Serum CA19-9 levels are elevated in some cases [40, 41].

Inflammatory pseudotumors usually have a good prognosis. Conservative treatment can include steroids, other anti-inflammatory drugs, and/or antibiotics, which can result in complete regression. Initial uncertainty about the diagnosis or local complications may lead to surgical excision.

Inflammatory pseudotumors in the liver are rare and account for less than 1 % of focal liver lesions [42–44]. They usually occur in adults between fourth and seven decades of life with a male predominance [45–47]. Common presenting symptoms include fever, abdominal pain, weight loss, and jaundice. The exact pathogenesis is not known, but an exaggerated inflammatory response to some infectious agent, autoimmune phenomenon, or systemic inflammation has been suggested as possible etiologies.

Inflammatory pseudotumors within the liver are usually solitary, but can sometimes be multiple (about 20 %). Single inflammatory pseudotumors tend to be larger than multifocal lesions. Their size can vary from less than 1 cm to lesions to greater than 10 cm. More than half of the tumors are seen in the right hepatic lobe.

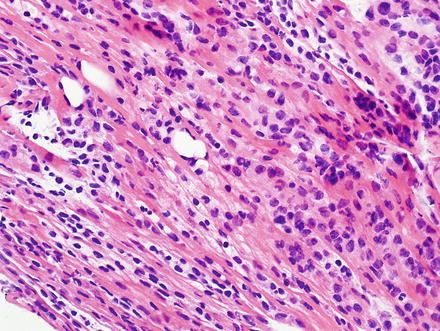

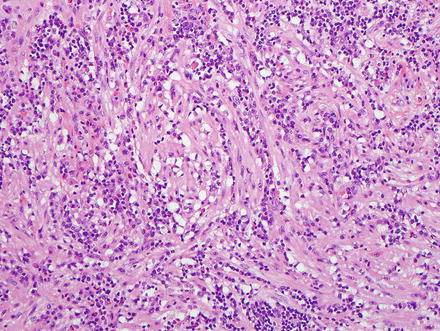

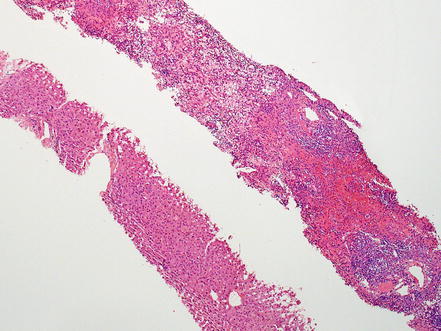

Grossly, they appear as well-circumscribed, firm, yellow or tan white lesions. Microscopically, the lesions have a prominent inflammatory infiltrate with a predominance of mature polyclonal plasma cells in a background of fibrous tissue and spindled myofibroblastic proliferation (Figs. 1.22 and 1.23). There should be no atypia in the spindled myofibroblastic cells and mitoses are absent to very rare. The collagen can be dense or loose. Storiform areas, while not diagnostic, suggest the possibility of IgG4-related disease (see below). Lymphocytes, neutrophils, macrophages, and eosinophils are also variably present and can sometimes be focally prominent. Inflammatory pseudotumors may also show xanthogranulomatous inflammation with multinucleated giant cells (Fig. 1.24). Occasionally, lymphoid aggregates including follicles may also be seen (Fig. 1.25).

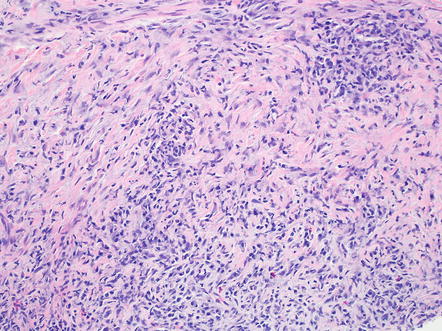

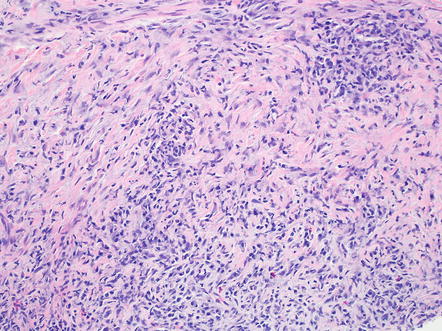

Fig. 1.22

Inflammatory pseudotumor. Aggregates of plasma cells in the background of myofibroblastic proliferation

Fig. 1.23

Inflammatory pseudotumor. High-power view showing a predominance of plasma cells

Fig. 1.24

Inflammatory pseudotumor. Multi-nucleated giant cells are admixed with the plasma cells

Fig. 1.25

Inflammatory pseudotumor. A lymphoid aggregate with germinal centers is seen

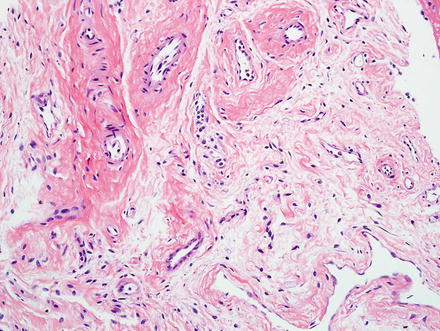

The hepatic-vein tributaries and portal-vein branches may show obliterative phlebitis, similar to the phlebitis seen in type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis. The phlebitis tends to involve medium- to larger-sized portal veins and is more common in single lesions than in multifocal disease. In other cases, the occluded vessels may have little inflammation, probably reflecting older lesions. Bile ducts can also be identified within inflammatory pseudotumors, showing periductal lymphoplasmacytic infiltration with or without concentric periductal fibrosis (Fig. 1.26).

Fig. 1.26

Inflammatory pseudotumor. Bile ducts within the lesion may show periductal plasma cell infiltrates with concentric periductal fibrosis

Immunohistochemically, the spindled cells in inflammatory pseudotumors are often vimentin and smooth muscle actin-positive, while immunostains for anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) are negative. Patchy cytokeratin staining may be seen in some inflammatory pseudotumors [43].

The differential diagnosis includes a number of entities and a diagnosis of inflammatory pseudotumors is always one of exclusion. The edge of an abscess can look essentially identical on biopsy and should be included in the differential diagnosis of biopsy specimens. In addition, syphilis can cause lesions that are essentially identical to idiopathic inflammatory pseudotumors (Fig. 1.27) [48]. Silver stains are often not sensitive enough to detect the organisms, but immunohistochemistry works very well (Fig. 1.28).

Fig. 1.27

Inflammatory pseudotumor, syphilis. This case of syphilis involving the liver looks like an ordinary inflammatory pseudotumor

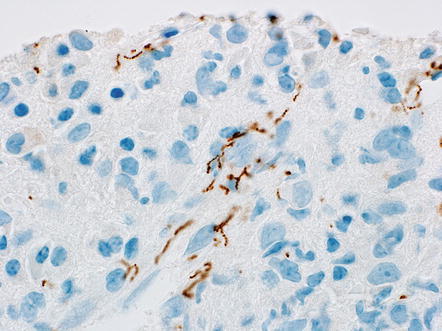

Fig. 1.28

Inflammatory pseudotumor, syphilis. A silver stain in this case showed few if any definite organisms, but an immunostain nicely highlights the organisms

Studies have also suggested a relationship between IgG4 and some inflammatory pseudotumors [49–51]. In fact, a subset of hepatic inflammatory pseudotumors have numerous IgG4-positive plasma cells (Fig. 1.29) and they may be part of the IgG4-related disease complex. For this reason, IgG4 stains are helpful in many cases. A cut off of at least ten IgG4-positive plasma cells per high power field is often used for the diagnosis of IgG4-related disease complex. However, even cases with increased IgG4-positive plasma cells need to be correlated with clinical and serological findings, as increased numbers of IgG4-positive plasma cells only suggest the diagnosis and do not establish it.

Fig. 1.29

Inflammatory pseudotumor. An IgG4 immunostain highlights numerous IgG4-positive plasma cells

There are a number of other less common tumors to consider in the differential. Some angiomyolipomas can have striking inflammation and mimic inflammatory pseudotumors, but tumor positivity for HMB-45 and Melan-A will help make the correct diagnosis [52]. Some liposarcomas can also have areas that closely resemble inflammatory pseudotumors [53]. Epstein-Barr virus-related follicular dendritic cell tumor is also in the differential, but this rare tumor will be positive for CD21 and CD35 by immunohistochemistry [54]. Finally, inflammatory pseudotumors can be associated with carcinomas that obstruct the common bile duct, with subsequent infectious cholangitis and inflammatory pseudotumor formation [40]. Thus, a diagnosis of an inflammatory pseudotumor should be followed by further studies to rule out other disease processes, including neoplasms and biliary tract obstruction. Overall, multifocal lesions are more commonly associated with chronic biliary tract disease than single lesions.

1.7 Heterotopia

Heterotopic tissues are usually found incidentally in the liver, either during surgery or at the time of autopsy. Exceptions do occur, however, in which they present with a mass lesion.

1.7.1 Pancreatic Acinar Metaplasia

Pancreatic acinar metaplasia is typically a microscopic finding, and not a grossly evident lesion. Pancreatic acinar metaplasia is relatively common and is found in approximately 4 % of livers [55, 56]. In explanted livers, pancreatic acinar cell metaplasia is most commonly seen in cirrhosis from chronic hepatitis C [55]. In non-cirrhotic livers, the metaplasia tends to be more commonly seen with chronic biliary tract disease. The metaplasia consists of small clusters of compactly packed cells that closely resemble pancreatic acinar cells (Figs. 1.30 and 1.31). They are usually located near septal-sized or larger bile ducts, often in the hilar region. Pancreatic acinar metaplasia is amylase-positive and appears to develop from a progenitor cell and likely does not represent true heterotopia [55, 57]. However, rarely true heterotopias occur and can show islet cells, ductal structures, and acini [58]. Choledochal cysts and retention cysts have been reported in association with heterotopic pancreatic tissue in the liver [58, 59]. Ductal adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine tumors can very rarely arise from intrahepatic heterotopic pancreas [60].

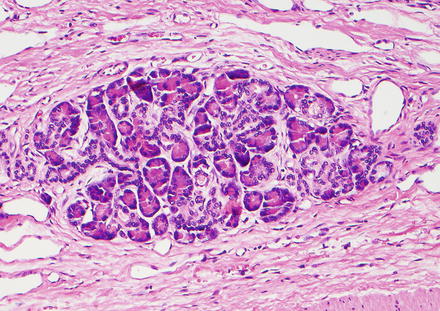

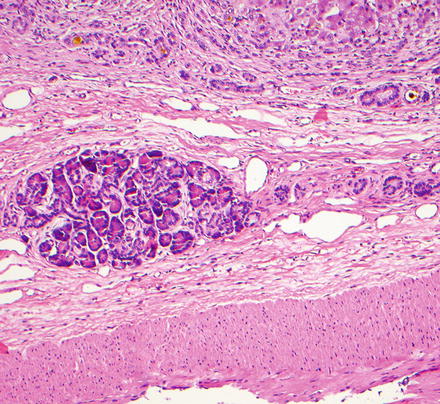

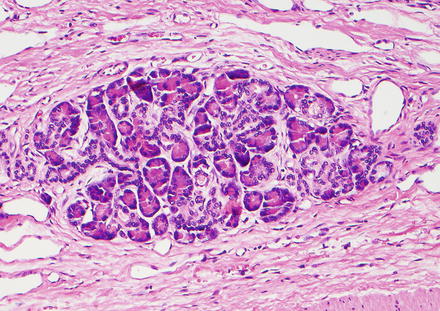

Fig. 1.30

Pancreatic heterotopia. Pancreatic heterotopia shows clusters of closely packed acinar cells in the vicinity of bile ducts (right)

Fig. 1.31

Pancreatic heterotopia. The acinar cells feature granular basophilic cytoplasm typical of exocrine pancreatic acini

1.7.2 Adrenal Tissue

Adrenal tissue can be found in the liver in a few different settings; it can represent adrenal-hepatic fusion, adrenal-hepatic adhesion, or adrenal rest tumors [61, 62]. Fusion is defined as adhesion of the liver and right adrenal cortex with some intermingling of the respective parenchymal cells [62, 63]. Fusion may also occur between the liver and spleen [64], but this is extremely rare. Adrenal-hepatic adhesion, on the other hand, is distinguished from fusion by the presence of a capsule, or at least a remnant of a capsule, between the two organs. Sometimes the distinction is a bit arbitrary. With adhesions, the adrenal glands show marked diminution or absence of the adrenal medulla and can sometimes be confused with a neoplastic process. Fusion, a condition found in approximately 10 % of individuals, is usually unilateral and not associated with adrenal impairment. Its incidence significantly increases with older age groups, suggesting that it may be an aging phenomenon [62]. No causative relationship exists between these conditions (fusion and adhesion) and pathological conditions of either of the two organs [61, 62].

Adrenal rest tumors, on the other hand, consist of heterotopic adrenal cortical tissue located within the capsule of the liver. They are distinguished from adrenal-hepatic fusion and adhesion by being completely separate from the right adrenal gland [65]. These localized collections of adrenocortical tissue occur most frequently in abdominal and pelvic sites, but can rarely involve the liver [66]. Adrenal rest tumors can occasionally secrete corticosteroids, resulting in features of Cushing’s syndrome and virilization in females; serum and urine cortisol levels are increased in this setting [65]. Radiologically, a mass lesion can be detected, often with calcifications. Grossly, the lesions are lobulated and encapsulated, with a cut surface reminiscent of normal adrenal cortex [65].

Microscopically, the adrenal rests consist of round to polygonal cells with round to oval nuclei and finely granular to clear cytoplasm, arranged in cord-like structures (Figs. 1.32 and 1.33), and separated by vascular channels or collagen bands. Multinucleated cells and occasional cells with marked pleomorphism can be observed. The interface with the surrounding liver ranges from areas of encapsulation to areas of infiltrative growth, with foci of entrapped hepatocytes within the tumor. A rim of normal adrenal cortex adjacent to the tumor has also been described in one case. The adrenal rests are negative for HepPar-1, RCC, and EMA, positive for inhibin and Melan-A, and have variable expression of Synaptophysin and NSE (Figs. 1.34, 1.35 and 1.36). This immunoprofile helps differentiation of adrenal rest tumors from other resembling neoplasms such as hepatocellular neoplasms and metastatic renal cell carcinoma. These lesions are benign and are usually treated by surgical resection of the tumor.

Fig. 1.32

Adrenal rest tumor. The lesion consists of nests and cord-like collections of polygonal cells identical to adrenal cortical cells, with round to oval nuclei and finely granular to clear cytoplasm. Hepatic parenchyma is also seen in the right side of the image, for comparison

Fig. 1.33

Adrenal rest tumor. A higher power image shows the polygonal cells with clear cytoplasm

Fig. 1.34

Adrenal rest tumor. A Hepar1 immunostain highlights the hepatocytes but is negative in the adrenal rest tumor

Fig. 1.35

Adrenal rest tumor. The tumor cells are positive for inhibin

Fig. 1.36

Adrenal rest tumor. The tumor cells are positive for synaptophysin

1.7.3 Other Tissues

Other tissues that can be found entirely within the liver include spleen [67–70]. Splenic heterotopia (also known as intrahepatic splenosis) is rare, but can present as a mass lesion that mimics primary hepatocellular carcinoma [69] or metastases [67, 68, 70]. Histologically, the lesion shows typical spleen morphology (Figs. 1.37, 1.38 and 1.39). The problem in diagnosis is often to first entertain the possibility of heterotopic spleen, but once this is considered, the diagnosis is usually straightforward. Thyroid heterotopia is extremely rare; one report was described in association with trisomy 18 [71].

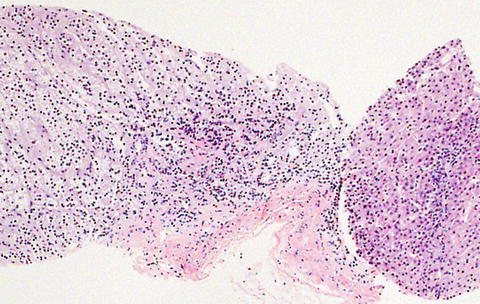

Fig. 1.37

Intrahepatic splenosis. A liver biopsy shows liver parenchyma (lower left) and splenic tissue (upper right)

Fig. 1.38

Intrahepatic splenosis. The continuity with hepatic parenchyma confirms the intrahepatic location

Fig. 1.39

Intrahepatic splenosis. There is typical splenic morphology, featuring both red and white pulp

1.8 Juvenile Xanthogranuloma

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (also called nevoxanthendothelioma) is a histiocytic disorder that primarily affects young individuals in the first two decades of life and most often presents with a solitary cutaneous lesion. The typical skin lesions are small yellowish to erythematous nodules (most ≤1 cm) that are located in the head and neck region. Microscopically (Fig. 1.40), they have a pushing border and consist of a mixture of mononuclear cells, multinucleated cells (with or without Touton features), and spindle cells (interspersed or aggregated, but not always present). The mononuclear cells and giant cells occasionally have a xanthomatous appearance and sometimes feature nuclear grooves reminiscent of Langerhans cells. In approximately 10 % of cases, the mononuclear cells demonstrate nuclear atypia and mitotic activity. The classical Touton giant cells are present in 85 % of cases, but can be sparse or common in any given case. Touton giant cells have a central wreath of nuclei and a peripheral rim of cytoplasm (with or without vacuoles). Eosinophils, and less often lymphocytes and plasma cells, can also be seen. The lesional mononuclear cells are positive for CD68, factor XIIIa, S100 (weak), and are negative for CD1a.