Fig. 8.1

Trends in hepatic resection over a 10-year period showing increased utilization of segmental resections over major hepatectomy, reduced use of perioperative blood transfusion, and decreased morbidity and mortality (From Fan et al. 1999 with permission)

Despite these points, there is a significant risk of complications associated with liver resection surgery. Often this is related to the underlying pathology and indications for which the surgery is being performed.

Intraoperative bleeding is the major complication associated with hepatic lobectomy, hemihepatectomy, partial hepatectomy, or extended hepatectomy, especially from injury to large portal inflow structures, the inferior vena cava, or the hepatic venous outflow structures. Adequate exposure and knowledge of the possible anatomical points is necessary to reduce risk of mishap. Excessive oozing from multiple small veins is especially important to control. Air embolus is another rare but severe life-threatening complication. Postoperative hepatic failure continues to remain a severe and lethal complication following any form of major hepatectomy. Postoperative bile leak, biloma, bile collection, bile ascites, and biliary fistula remain relatively common complications following major hepatic resection. Tumor recurrence following resection of malignancy is a significant problem and is integrally related to the pathology and width of resection margin of normal liver around the lesions(s). Coagulopathy and infection are other potentially serious complications and may lead to multisystem organ failure and death.

With these factors and facts in mind, the information given in these chapters must be appropriately and discernibly interpreted and used.

The use of specialized units with standardized preoperative assessment, multidisciplinary input, adequate surgical volume, and high-quality postoperative care is essential to the success of liver resectional surgery overall and can significantly reduce risk of complications or aid early detection, prompt intervention, and cost.

Important Note

It should be emphasized that the risks and frequencies that are given here represent derived figures. These figures are best estimates of relative frequencies across most institutions, not merely the highest-performing ones, and as such are often representative of a number of studies, which include different patients with differing comorbidities and different surgeons. In addition, the risks of complications in lower or higher risk patients may lie outside these estimated ranges, and individual clinical judgement is required as to the expected risks communicated to the patient, staff, or for other purposes. The range of risks is also derived from experience and the literature; while risks outside this range may exist, certain risks may be reduced or absent due to variations of procedures or surgical approaches. It is recognized that different patients, practitioners, institutions, regions, and countries may vary in their requirements and recommendations.

Limited Liver Resection (Segmentectomy, Sectorectomy, and Sector Resection)

Description

General anesthesia is utilized for segmental liver resection. The aim of performing a segmental or sectorial resection is to remove a solitary benign or malignant liver lesion, although several lesions may be amenable to segmental resection or to treat segmental biliary strictures, trauma, or abscess. The goal is to achieve negative margins around tumor(s), as well as excising any liver parenchyma devascularized from occlusion of segmental portal inflow. Segmental resections can be combined with a contralateral major hepatectomy for complete resection of bilateral disease. Segmental resection is also used in patients with underlying liver dysfunction (e.g., cirrhosis, steatosis, or fibrosis) at risk of liver failure who would not tolerate a major liver resection. Segmental or sectorial resection is commonly utilized in patients with solitary hepatocellular carcinoma or in patients with a single metastasis (e.g., colorectal carcinoma, melanoma).

Anatomical Points

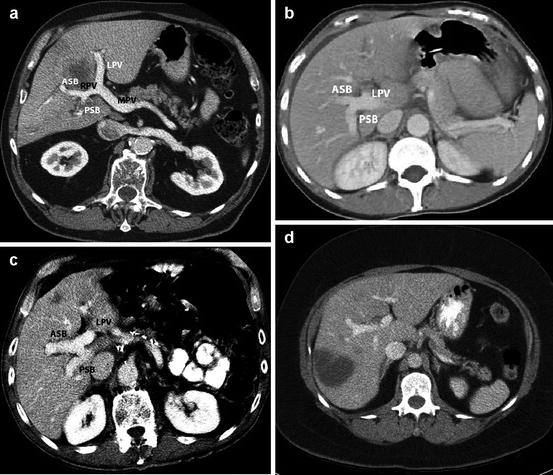

The anatomical points in the performance of segmentectomy or sectorectomy is primarily dictated by the possible variant inflow that can occur with the right lobe of the liver. The right hepatic inflow that supplies segments 5, 6, 7, and 8 arises from the junction of the right and left portal vein. In a majority of cases, there is a common right portal vein that branches into the right anterior sectorial and right posterior sectorial branches (Fig. 8.2a). However, the main right portal vein leading to the right anterior and right posterior sectorial branches may be absent, instead originating at the same junction as the left portal vein (Fig. 8.2b). Another main portal anatomical points can occur with the early takeoff of the right posterior sectorial vein, with the bifurcation then occurring at the left portal vein and the right anterior sectorial vein (Fig. 8.2c). Inflow within the right hepatic lobe can also vary with segment-6 inflow branches originating from the anterior sectorial branches and creating an isolated segment-7 branch (Fig. 8.2d). This anatomical point is important to ensure that only a single segment of inflow is occluded instead of the entire right lobe or the anterior or posterior segment, respectively.

Fig. 8.2

(a) CT scan showing normal portal venous anatomy with the left portal vein (LPV) and right portal vein (RPV) arising from the main portal vein (MPV). The RPV divides into an anterior sectorial branch (ASB) supplying segments 5 and 8 and posterior sectorial branch (PSB) supplying segments 6 and 7. (b) CT scan showing trifurcation of the main portal vein into LPV, ASB, and PSB. (c) CT scan showing early takeoff of the PSB from the MPV with subsequent division of the remaining branch into LPV and ASB. (d) CT scan showing segment-6 (SEG 6) branch arising from the ASB while the segment-7 (SEG 7) portal branch arises from the MPV

Table 8.1

Limited liver resection (segmentectomy, sectorectomy, and sector resection) estimated frequency of complications, risks, and consequences

Complications, risks, and consequences | Estimated frequency |

|---|---|

Most significant/serious complications | |

Infection | |

Wound | 5–20 % |

Intra-abdominal (including liver/liver bed/subphrenic abscess) | 5–20 % |

Intrathoracic (pneumonia, pleural) | 5–20 % |

Mediastinitis (if vena cava isolation is used) | 0.1–1 % |

Systemic | 1–5 % |

Bleeding overall | 5–20 % |

Arterial, venous (caval, renal, portal, hepatic, or lobar vessels) | 1–5 % |

Raw liver surface | 5–20 % |

Extrahepatic | 1–5 % |

Hematoma formation (including subcapsular hepatic) | 1–5 % |

Biliary obstruction | 0.1–1 % |

Bile leak | 1–5 % |

Biliary collection | 1–5 % |

Bile duct stenosis | 0.1–1 % |

Biliary ascites | 0.1–1 % |

Biliary fistula | 0.1–1 % |

Hyperbilirubinemia | 50–80 % |

Jaundice | 1–5 % |

Common/extrahepatic/intrahepatic bile duct injury | 1–5 % |

Unresectability of malignancy or tumor/involved resection marginsa | Individual |

Recurrence of malignancya | Individual |

Serous ascitic collection | 5–20 % |

Liver injury (to remaining liver) | 1–5 % |

Pancreatitis/pancreatic injury/cyst/fistula | 1–5 % |

Bowel injury (stomach, duodenum, small bowel, colon) | 1–5 % |

Thrombosis | |

Arterial | 1–5 % |

Venous | 1–5 % |

Surgical emphysemaa (major) | 1–5 % |

Pneumothorax | 50–80 % |

Cardiac arrhythmias (major) | 1–5 % |

Myocardial injury/cardiac failure/myocardial infarction (hypotension) | 1–5 % |

Small bowel obstruction (early or late)a [Ischemic stenosis/adhesion formation] | 1–5 % |

Reflux esophagitis/pharyngitis/pneumonitis | 1–5 % |

Coagulopathy | 1–5 % |

Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy | |

aConsumption transfusion (large bleed) | |

Gastrointestinal erosion, ulceration, perforation, hemorrhage | 1–5 % |

Multisystem failure (renal, pulmonary, cardiac failure) | 1–5 % |

Deatha | 1–5 % |

Rare significant/serious problems | |

Budd-Chiari (acute) | 0.1–1 % |

Liver failure (ischemia, toxicity, acute hepatic necrosis) early or late | 0.1–1 % |

Aspiration pneumonitis | 0.1–1 % |

Portal venous thrombosisa | 0.1–1 % |

Deep venous thrombosis | 0.1–1 % |

Air embolus (major) | 0.1–1 % |

Renal/adrenal injury renal vein | 0.1–1 % |

Diaphragmatic hernia/injury/paresis | 0.1–1 % |

Pericardial effusion | <0.1 % |

Thoracic duct injury (chylous leak, fistula)a | <0.1 % |

Splenic injury | 0.1–1 % |

Conservation (consequent limitation to activity; late rupture) | |

Splenectomy | |

Hepatic rupturea | 0.1–1 % |

Hepatitis (drug, CMV, recurrent)a | 0.1–1 % |

Renal failure (hepatorenal syndrome)a | 0.1–1 % |

Hyperglycemia | 0.1–1 % |

Hypoglycemia | 0.1–1 % |

Wound dehiscence | 0.1–1 % |

Less serious complications | |

Pain/tenderness [rib pain (sternal retractor), wound pain] | |

Acute (<4 weeks) | >80 % |

Chronic (>12 weeks)a | 5–20 % |

Paralytic ileus | 20–50 % |

Muscle weakness (abdominal atrophy due to denervation esp. subcostal incision) | 1–5 % |

Nutritional deficiency – anemia, B12 malabsorptiona | 5–20 % |

Wound scarring (poor cosmesis/wound deformity) | 5–20 % |

Incisional hernia formation (delayed heavy lifting) | 1–5 % |

Nasogastric tubea | 1–5 % |

Blood transfusion a | 5–20 % |

Wound drain tube(s) a | 50–80 % |

Perspective

See Table 8.1. Potential major complications of hepatic resection are bleeding and biliary leakage. Bleeding during segmentectomy and sectorectomy will occur primarily from the outflow hepatic veins. These are thin walled veins that tear easily and can develop lateral tears, which can extend up to the main venous branches or to the inferior vena cava underneath intact hepatic parenchyma. Thus, any form of segmentectomy or sectorial resection must identify all of the major hepatic venous outflow structures to ensure adequate hemostasis and to minimize blood loss. Biliary leakage is primarily a problem in patients who are undergoing some form of bile duct resection and requiring biliary reconstruction (Tanaka et al. 2002). Biliary leakage is less common when performing a segmentectomy or sectorectomy and primarily will occur because of the inadvertent transection of a (small) bile duct without adequate closure. The performance of a segmentectomy should not be automatically assumed to be a lesser operative procedure compared to hepatic lobectomy or some form of extended hepatic lobectomy, since the anatomical relationships may be more complex to appreciate and the resections can be technically more demanding than lobectomies. Recent evaluations have shown that intraoperative blood loss is significantly greater when a nonanatomical resection is performed, compared to an anatomical hepatic segmentectomy or lobectomy, principally because of difficulty with small venous outflow control during resection. Nonanatomical resection is also associated with a higher margin positivity rate (DeMatteo et al. 2000). All segmental resections are not of similar difficulty. A segment-3 resection is technically more straightforward compared to a segment-8 resection. The accessibility of the inflow and outflow structures, the presence of variant anatomy, the depth and quality of the liver parenchyma, and the patient body habitus can make various types of segmental resections more difficult in certain patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree